by Laura McFarland | Jan 31, 2018 | Applied Principles, Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Equine Assisted Trainings, Personal Growth

When we sense God is with us, our relationship with God develops through the experience of ‘connection through attachment’, which is a perceived sense of nearness. At other times, perhaps times of great loss or suffering, we may sense God is nowhere to be found. A joyful sense of connection seems to dissolve into a deep well of emptiness with no consolation. We may then experience what 16th-century mystic, John of the Cross, described as the “dark night of the soul.” In actuality, just as winter makes way for spring, this period of perceived absence and isolation potentially gives birth to an even greater spiritual resilience – an abiding sense of connection that survives even our darkest nights. We are invited into a deeper and more mature intimacy with God through the experience of detachment.

Both science and religion point to the fundamental forces and patterns of the universe as being essentially intimate and relational. While the language and the narrative may differ, the theme is the same. We exist in an utterly relational universe. Creation is ongoing as a dance without end. We, ourselves, are created over and over again as our bodily cells grow, mature, and die off, but not before giving life to countless new cells with new variations made possible through the myriad relationships and interactions that occur within our physical bodies and between our bodies and our external environments. No doubt similar processes are at work in the realms less observable, such as in the inner workings of our minds and hearts. Acknowledging this, all major spiritual traditions teach paths of transformation. If our minds and hearts are patterned like everything else in the knowable universe, they are always in the process of changing and evolving. We seek spiritual paths and, increasingly, science-based paths, to take a more active role in our personal evolution involving the growth and transformation of our hearts and minds.

I have prioritized this interest in my life from a very young age. I have learned from different spiritual paths as well as from the science of depth psychology, and more recently, neuropsychology, to help me navigate the journey toward a more whole and healthy life, characterized by a more authentic and loving relationship with myself and with others.

When I encountered Natural Lifemanship several years ago, I immediately recognized the opportunity to practice in practical, embodied ways many of the same processes at work in my spiritual journey. I’ve often reflected on how the principle of pressure has worked in my life to help me to grow more connected with self, with others, and with God. I’ve noticed the ways I’ve experienced pressure, at first as a kind of gentle nudging in my heart toward some kind of change process not fully understood. On some level, I feel I am asked to trust and cooperate with a process, although I may have no idea where it is leading. At the early stages I can’t quite put words to what is being asked of me or know how to respond, but the sense of pressure persists, gently increasing until I can’t ignore it anymore. At this point I start actively seeking an answer, which is Natural Lifemanship’s definition of resistance – not an undesirable thing, rather a positive search for an answer in response to pressure. In fact, my life’s most important lessons and periods of growth came about through the process of acknowledging some internally felt pressure, struggling with it, and finally cooperating, allowing it to change me in ways I never could have foreseen and never would have experienced without my willingness to trust, listen and observe, and cooperate, often blindly, with what I sense is being asked of me.

Another way NL has given concrete language to a pattern I’ve experienced in my deeply personal relationship with God is through the notion that the relationship grows through both attachment and detachment. Attachment in our spiritual lives refers to those wonderful life episodes and experiences where we acutely sense the presence of God, or a higher power, or a deeply felt connection with something greater, in our lives. This is usually felt as a consoling, meaningful, hopeful, warm and embracing presence utterly nurturing and sustaining us. It gives us the sense that all is well and that we can endure whatever struggles we may be experiencing.

The writers of the Judeo-Christian bible and many other religious texts all describe this sort of relationship, where faith is built through such affirming experiences. The early stages of faith can be described as a connection being built through attachment, or what is felt as presence, or the responsiveness of the subject of faith. This is even spoken of in Buddhism, a spiritual path generally unconcerned with the question of an ontological God, but essentially concerned with one’s epistemological relationship with What Is, with reality. Reality is what it is but our lens or our way of seeing and perceiving reality may be clear or it may be clouded. In the case of Buddhism, the lens of perception is polished through practice, but human nature is such that humans won’t persist at practice without some sense of reward. So it is said even in some forms of Buddhism that faith grows at the early stages as the pattern of the universe, being inclined toward evolution, reinforces a sincere practitioner’s efforts in faith (causes) by producing tangible effects experienced as answers to prayers.

There comes a time, however, when faith is tested. There are periods of our lives for many of us in which we feel disconnected from the faith that has sustained us. We experience no sensation whatsoever of the presence of God. Our vivid, Technicolor faith lives seem to have become monochrome and dull. To the extent that we have felt a deep connection before, we may feel utterly abandoned. We may cry, as many of the psalmists and even as Jesus did, “my God, why have you left me?” John of the Cross poetically described this dimension of our spiritual lives as “the dark night of the soul.” As a spiritual director, he did not wish the dark night on anyone but listened for it in those he counseled. Not everyone will experience a dark night, for there are those who may never cease to find consolation when they seek it in their daily lives and normal activities of faith. John maintained that one shouldn’t give up these routines or activities so long as they are producing satisfying results. This is a blessing in and of itself.

Some, though, are invited into a deeper intimacy with God through a fundamental testing of our faith. John of the Cross describes it this way (paraphrased): Our hearts were made for intimacy with the One who created us, and nothing less than a connection directly with our Source will satisfy us at the deepest level of our soul. And yet in our lives, we easily become attached to the more surface consolations available to us and we may rest our identity in something less than our truest selves – which is our true nature as children of God. God, therefore, weans us off of our reliance on consolations – or felt presence – by seeming to withdraw from us. The dark night can, therefore, be understood in NL terms as God, or our relationship with the Divine (however we know the Divine), practicing connection with detachment with us.

The goal is that we begin to cultivate a secure attachment, or enduring sense of connection – one we readily turn to regardless of whether we perceive God as being with us, or not. In Christian theology, God enacted the same pattern by being with humanity (through Jesus’ human presence) to withdrawing from humanity (Jesus’ death) to presence again (appearances after the resurrection) to withdrawal (Pentecost) but at the same time gracing humanity with the presence of the Holy Spirit, also known as “the comforter” or consoler. This pattern of attachment and detachment to build secure attachment (connection) in relationship is written into the gospel, itself.

My hope for all who read this is that in those moments of despair or loneliness and isolation, you find peace knowing that your Source of comfort and of life itself may not always seem near but it is always within. Know that perhaps you are being invited to discover and to rediscover an even more enduring sense of connection in the depths of your lives, one that doesn’t rely on any evidence of response (such as answered prayers) or a felt sense of presence. May we all develop a deep connection with self and the indwelling Spirit that is attuned to the still small voice within. The reward of such a sense of connection is the relationship itself – a “secure attachment” both earned and given by grace.

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Sep 7, 2017 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Rhythmic Riding Immersion Blogs, The Latest in Equine Assisted Therapy and Learning

…Why Do We Ride Horses

In Natural Lifemanship, mounted work is an integral part of our model of trauma-focused equine assisted psychotherapy (TF-EAP). However, I recently read a published article arguing that horseback riding is contraindicated in the treatment of military veterans with moral injury. The authors suggest that mounted work victimizes the horse and puts the client in a place of power, domination, and control. While we do not disagree that relationships characterized by power, domination, and control are indeed contraindicated for this population and for others, we feel this article begs two important questions with respect to equine assisted psychotherapy: 1) what benefits are accrued uniquely through mounted work that renders it an integral component of TF-EAP; and 2) is the aforementioned power dynamic an inevitable byproduct of riding, or is there a way to engage in mounted work that promotes its benefits without resulting in a damaging relational dynamic? Natural Lifemanship strongly contends that riding has powerful therapeutic benefits that cannot be obtained by other means and is contraindicated only when it is not done in a connecting and mutually beneficial way. Let’s explore why this matters – therapeutically speaking.

The physical benefits of horseback riding are well documented in the literature. Due to the many physical benefits, specifically related to balance, gait, and psychomotor difficulties, there have been many efforts to produce a horseback riding simulator for the purposes of physical rehabilitation and training. A company in Japan claimed, “almost 100% reproducibility (of the horse’s movement) has been achieved.” The simulator is not able to walk, but it does synchronize the six major movements of the horse while under saddle. However, in a publication about this simulator, the authors note that it does not have a mechanism “which catches the center of gravity movement of the rider.” They go on to explain that this important aspect of carrying is “similar to the case where the mother who is carrying her baby on her back is able to keep her balance compensating for the baby’s movement.” The simulator can reproduce movement, but it cannot reproduce the responsiveness of a sentient being carrying another. The ability of the horse to respond to the rider’s body and balance, much like a mother carrying her child, is more than just convenient. This responsiveness between the carrier and the one being carried activates physical attunement and connection in the relationship – the horse adjusts to the rider, and eventually, the rider adjusts to the horse. Movement alone organizes the lower regions of brainstem and diencephalon, but movement with attunement to the other and responsiveness is the relational connection, which reaches higher in the brain, targeting the limbic system. So while the movement of a horse can be reproduced, even the scientists responsible admit that there are limitations to riding a non-responsive machine. This is merely the beginning of what makes riding such an important part of treatment for mental health disorders.

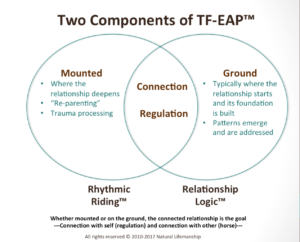

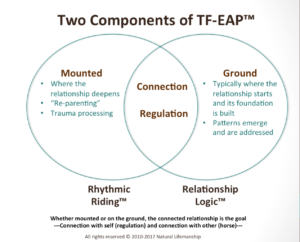

In Natural Lifemanship there are two major components of TF-EAP – Relationship Logic and Rhythmic Riding. Relationship Logic takes place on the ground and Rhythmic Riding takes place on the horse’s back. Whether mounted or on the ground the connected relationship is the goal. This is the most important aspect of why riding a living, breathing horse is more valuable than using a tool – connection between horse and rider can make all the difference.

In Natural Lifemanship there are two major components of TF-EAP – Relationship Logic and Rhythmic Riding. Relationship Logic takes place on the ground and Rhythmic Riding takes place on the horse’s back. Whether mounted or on the ground the connected relationship is the goal. This is the most important aspect of why riding a living, breathing horse is more valuable than using a tool – connection between horse and rider can make all the difference.

So why does connection matter so much? The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT), developed by Dr. Bruce Perry, is one of the primary problem-solving approaches that guide the sequence and progression of treatment in TF-EAP, for example, when and in what way mounted work is used.

All rights reserved © 2007-2017 Bruce D. Perry

Dr. Perry divides the brain into four main regions:

1. Brainstem

2. Diencephalon

3. Limbic System

4. Neocortex

We do realize that this is an oversimplification of very complex neurological systems. Nonetheless, we have found that simplification makes this information more accessible in clinical practice.

In Trauma-Focused Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, our primary goal is to integrate these 4 major regions of the brain so that the different regions can communicate effectively. For health and well-being, it is necessary for them to do so because they are responsible for all the major functions that support us. The brainstem is responsible for automatic systems like breathing and heart rate, as well as our survival responses of fight/flight/freeze. The diencephalon directs our movement and motor skills. The limbic system is responsible for connection, bonding, and emotional experience. And finally, the uppermost region, the neocortex is responsible for our abstract and concrete thought. Imagine if any of these major regions were to be significantly hindered – leading a typical life would be quite difficult.

Why does an integrated brain, one that communicates easily across regions, matter in everyday life? Ultimately, it makes self-regulation, and therefore self-control, possible – the neocortex is able to guide the entire brain and when necessary override impulses for fight, flight, or freeze in the lower regions. When the neocortex is integrated with the rest of the brain, we can think before we act. For this to happen there have to be actual neuronal connections (think of roads in our brain) going from the lower regions of the brain up into the neocortex. This can only happen when all 4 regions have gotten that rhythmic, predictable input that helps them grow and operate in an organized fashion. The limbic system is in charge of connection…bonding, attachment, and therefore key in having healthy relationships. It is also crucial to understand that the limbic system is nested between the upper region of the neocortex and the lower regions of the diencephalon and brainstem. Without an organized and functioning limbic system – not only does one’s ability to connect falter, but the rest of the systems do as well. The disorganized limbic system interferes with all other cross-brain communication.

Additionally, an integrated brain with adequate cross-brain connections or pathways (making it possible for the entire brain to work together) results in a secure attachment pattern. Children and adults with a secure attachment pattern are able to feel connected and secure in their intimate relationships, while still allowing themselves and their partner to move freely. Numerous longitudinal studies have shown that infants and toddlers with a secure attachment to a primary caregiver do better during adolescence and adulthood in a variety of areas related to self-regulation, and relationship with self and others. With this foundation in place, they are more resilient when traumatic events occur. For example, research has shown that securely attached individuals in the military report far fewer incidences of PTSD symptoms. For those who didn’t develop a secure attachment in childhood, intentional therapies like Rhythmic Riding can form the cross-brain connections necessary for brain integration, what people in the attachment field call an “earned secure attachment.”

Lastly, an integrated brain can better process traumatic events and memories. Be on the lookout for a blog explaining how and why we use mounted work to process trauma through the use of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

While brain development, integration, and attachment all begin in utero, I would like to focus on what happens after birth to continue this process. In reference to the primary caregiver, I am going to use the terms “Mommy, Mama, or Mother”, primarily because my experience as a primary caregiver is as a mother. Also, I will utilize some pictures throughout the remainder of this blog for two reasons:

1. To illustrate some core concepts, and

2. As an excuse to show you some pictures of our adorable child! ☺

Okay, so something like this scenario represents the ideal situation: When a baby cries, the mother picks up the baby and starts to rock or bounce him, while talking with a soothing tone and cadence, or maybe singing. All the while the rhythmic heart rate of the calm and regulated mother is regulating the heart rate of the baby. The electromagnetic field of the heart, the rocking, and the calm, rhythmic sounds of the mother’s voice passively activate the brainstem and the more this rocking, singing, and talking occurs the more the brainstem continues to develop in an organized manner. Passive movement causes an active movement that happens even more as the baby grows and begins to manage some of his own balance when being held and rocked. This develops and organizes the diencephalon. When a child is upset in some way the mother feels a deep connection to her baby. Oxytocin is coursing through her body as her limbic system is activated and she is overcome with love for her child. As the brainstem and diencephalon develop and organize it makes it possible for the child to connect to the one holding him, and the limbic system of the child begins to further develop and organize. This occurs most remarkably, between 18-24 months, the sensitive period for attachment learning.

Each time the child is rocked, carried, touched, and moved in a rhythmic manner while also experiencing love and connection, pathways throughout the lower regions of the brain are formed – the beginning of integration. When these parts of the brain are integrated, it creates the ideal environment for the neocortex to optimally develop. The baby starts to explore and learn from his environment, and thus begins the development of concrete and abstract thought. The activation and organization of the limbic system is the crux of an integrated brain because it touches every part of the brain. For example, if the mother is disconnected, depressed, or struggling with something that makes it difficult for her to emotionally connect with her baby, the lower regions of the brain may develop through rocking, but limbic system development will be compromised. When the limbic system is shut down or disorganized, it is like a roadblock from the lower regions of the brain to the thinking part of the brain (neocortex). Remember, in an integrated brain the neocortex guides (and sometimes overrides) what is happening in the lower regions of the brain. Basically, connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks me sets the foundation for an integrated brain and secure attachment.

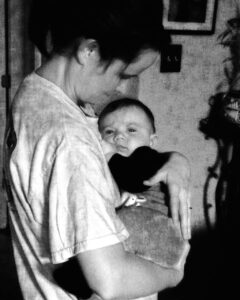

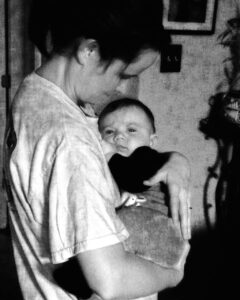

This is a Mommy. She can simultaneously provide rhythmic, regulating movement AND connection.

This child (who is quite adorable, indeed!) is connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks him.

It’s worth noting that this was a tough night and I had to work the next day! Just sayin’

This is a Daddy. Just to be fair, he too, can simultaneously provide rhythmic, regulating movement AND connection.

Please disregard the “do NOT take a picture of me!” look. (It’s somewhat genetic! ☺)

This was taken after a full day of Christmas shopping – thank goodness there was a rocker at Toys ‘R’ Us!

Many children (and, therefore, adults) do not get what is needed for their brains to integrate. Both sensory input and connection are needed for optimal brain development. When this input is unpredictable and arrhythmic the brain will be disorganized. When it is lacking, like in cases of neglect, development and organization are compromised. Additionally, trauma that occurs later in life, like military combat, can compromise integration. When we live in a situation for a period of time in which the survival centers are hyper-activated and the limbic system is hypo-activated, our brain changes, much like a muscle can, to accommodate the manner in which it is being used. In the trauma world, we understand the importance of somatosensory and sensorimotor input for organizing the developing brain and re-organizing the traumatized brain. In fact, numerous sensory tools are used for just this purpose – I have quite a few of them in my offi ce. Understanding how to best utilize these tools is an important part of trauma informed care, but this is not the focus of our conversation today. Many of these tools (pictured to the left) help to organize and regulate the brainstem with passive sensory input. However, they do not move our body or require that we move our body. They do not have the ability to form a relationship or connection with us. They can, though, work wonders for the dysregulated brainstem alone.

ce. Understanding how to best utilize these tools is an important part of trauma informed care, but this is not the focus of our conversation today. Many of these tools (pictured to the left) help to organize and regulate the brainstem with passive sensory input. However, they do not move our body or require that we move our body. They do not have the ability to form a relationship or connection with us. They can, though, work wonders for the dysregulated brainstem alone.

Another of my favorite tools is the rocking chair or glider. I think every therapist should have one of some sort in their office and every equine therapy program should have them in the barn and next to the spaces in which they meet with clients and horses. Rocking chairs pr ovide rhythmic, patterned, repetitive movement that is passive (activating and organizing the brainstem). In order to maintain posture and balance in the rocking chair, the muscles contract which is an active movement. Passive movement thereby causes active movement, which moves us up a bit higher into the brain – the diencephalon. The rocking chair is not, however, alive. It does not have a limbic system or the ability to connect, bond, or love another. Brainstem? Check! Diencephalon? Check! Yet, still no connection.

ovide rhythmic, patterned, repetitive movement that is passive (activating and organizing the brainstem). In order to maintain posture and balance in the rocking chair, the muscles contract which is an active movement. Passive movement thereby causes active movement, which moves us up a bit higher into the brain – the diencephalon. The rocking chair is not, however, alive. It does not have a limbic system or the ability to connect, bond, or love another. Brainstem? Check! Diencephalon? Check! Yet, still no connection.

This rocking horse cost about $40 (a bit inflated, because it’s “vintage”). There has been absolutely no upkeep or cost since the day I purchased it!

It offers rhythmic, regulating input, and earned its keep in Cooper’s one-year pictures, but still. . . it is not alive. No connection. You get what you pay for!

This is where horseback riding distinguishes itself. Being on the back of a horse can calm the nervous system through the movement that is inherently rhythmic, patterned, and repetitive. When a person is sitting on a horse, they do not have to create the rhythm or the movement, so the brainstem is passively regulated. Additionally, the sound of the horse’s feet and the movement that can be seen (like the movement of the horse’s head) all passively regulate the brainstem. As the horse moves, the rider’s muscles actively contract to maintain balance so the diencephalon is able to regulate. This is really great, but isn’t this something that could just be done with a rocking chair? It could definitely be argued that the movement of the horse is much more complex than that of a rocking chair. The physical and psychological benefits of this movement are so great that much effort has been made to re-create this complex movement. Yet, even if a simulator is able to fully reproduce this movement, the simulator still lacks the ability to activate and organize the limbic system, something we believe a live horse is definitely capable of …if we allow the horse to be more than just a “sensory tool.”

So, how do we ride horses in a way that fosters rhythmic limbic input? When the horse and rider are able to form a relationship based on attunement and connection, the limbic system is activated and organized. But, a paramount distinction is this kind of relationship is not possible when we operate from a paradigm of power, control, and domination. Pause for a moment and consider how often humans utilize power and control with horses – even if done gently. When the horse is encouraged, even through kind or humane techniques, to appease, submit, or dissociate, the horse becomes no more than a rocking chair or a horseback-riding simulator. When connected to the rider, the horse can help the rider to connect (engaging the limbic system), just like the mother who connects to the baby. The rider’s brainstem is passively regulated as the horse moves. The diencephalon is regulated, as the passive movement becomes active movement. The limbic system is activated and organized when the rider and horse connect and begin to respond one to another. Again, connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks me is how an integrated brain develops and a secure attachment is formed. If we are going to simply use the horse as a “sensory tool”, we might as well use actual sensory tools, rocking chairs, or the horseback riding simulator – all of which are much cheaper, require significantly less maintenance and carry less liability. The horse’s ability to connect is where the real healing happens, and it is what differentiates her from the many other sensory tools to which we have access.

Many would argue that if connection is ultimately the goal – why couldn’t therapists simply work with smaller animals like dogs? It is a legitimate question. However – while connection is absolutely necessary for the rest of the integration to occur, most clients who have experienced trauma need the passive regulation and motor stimulation of riding, which offers the sense of being carried AND connected with, all at once.

Lots of connection here! However, generally speaking, riding of the dogs and chickens is frowned upon in our home.

Really, no matter our age, sometimes we just need to be rocked and deeply heard in a connected relationship. I’ve watched horses do this in ways that still bring tears to my eyes.

This is a horse (Peanut to be exact!). He, too, provides rhythmic, regulating input and movement. He is an alive, sentient being, and most definitely capable of connection! (He is not a rocking chair or sensory tool)

Arguably, the fact that the horse can carry us, rock us, and connect with us makes her different than any other sensory tool and most other animals. With this comes quite the responsibility, however! The mental health and equine professional must learn how to tell the difference between compliance, appeasement, submission and. . . connection. Between dissociation and cooperation. We must continue to learn what connection looks and feels like as we relate to humans and horses, which typically requires that we understand ourselves, and that our intimate relationships are characterized by genuine connection. NOT an easy thing to do, but we believe it is necessary to really, intentionally help our clients reorganize their brains, learn new, healthy ways of connecting, and ultimately, heal.

Connecting with the one who carries me. . . the stuff brain integration and attachment are made of!

Let us return to the article I mentioned in the beginning. In this recent publication about why horseback riding is contraindicated for the psychological treatment of military veterans who have suffered moral injury, the authors do a beautiful job of describing the difference between psychotherapy and recreational activities. There is also wonderful information to help the reader distinguish between PTSD and moral injury. I very much appreciate the authors’ understanding of trauma and the insistence that clinicians need extensive training in a number of modalities to ethically work with this high-risk population. The authors also make it clear that horseback riding is not psychotherapy. In NL we definitely do not believe that horseback riding, in and of itself, is psychotherapy. On the majority, I agree with the distinctions made in this article.

However, the authors described riding in a way that, I must admit, made me cringe. There was talk about cross-ties which greatly restrict the horse’s movement and choice. The authors described saddles “made of dead animal hide,” and cinching up the horse in a way that compresses the two areas of the body that are the most vulnerable to attack by a predator. The description was quite graphic. The authors then, correctly in my opinion, conclude with the following statement: “We have rendered a horse docile and submissive and put a warrior in a position of control and dominance. We have established a predator/prey relationship. And for a war veteran, we have evoked the experience of being a perpetrator in control of a victim. Within the context of this duality, morally injured military veterans, struggling with feelings of worthlessness, self-hatred and inner evil because of what they have done or witnessed in combat, are being obstructed from the deep healing of soul that they so desperately need.”

Yes, I agree 100% that if this is the only paradigm you have for riding a horse, then riding is, indeed, contraindicated not only for military veterans with moral injury, but for any person seeking psychotherapy services, especially those who have experienced relational trauma. I strongly support that the authors challenged the status quo. They shed light on one of the ways in which EAP can, indeed, be damaging to our clients. There is, however, an assumption made by the authors with which I do not agree. I do not agree that the way they described the horse’s and the client’s experience of mounted work is the only experience possible. Horseback riding is not the problem. The paradigm of power, domination, and control is the problem, and this is a problem in any clinical setting, and honestly, in most horse-human relationships in general.

If your only paradigm is one of power, control, and domination, it is best that you utilize many of the amazing sensory tools available to clinicians, and don’t partner your clients with horses. A paradigm of power, control, and domination is damaging and traumatizing (and often re-traumatizing) for both the horse and the client, even if the domination and control is done “gently”. This paradigm is also a problem when building a relationship with a horse on the ground – this is not just about riding. A partnership based on connection, attunement, trust, and mutual respect starts on the ground, and all that is built on the ground must transfer to the horse’s back if mounted work is going to be restorative and transformative for both the horse and person. Again, this often requires an enormous amount of learning, practice, and a willingness to let go of old beliefs and patterns. The most intimate we will ever be with a horse is on his back – the place we can experience much joy but also much risk and vulnerability. If power, control, and domination are our only options at the height of intimacy, it might be worth dismantling the principles we employ, both mounted and on the ground.

Therapeutically speaking, the ability of the horse to carry, rock, and connect is powerful for brain integration, which all humans need and is at the core of the work we do with most of our clients. While we do ride to reach other therapeutic goals, the primary reason we ride horses in therapy is because of the horse’s uncanny and unmatched ability to “re-parent” and restore that which was lost in an organic and powerful way. Riding, then, is only contraindicated when that riding is not done in a connecting and mutually beneficial way. When horses are allowed to do what they do best – connect, and sometimes carry, then riding can be an unparalleled therapeutic intervention for lasting change. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater – what is necessary to do good work with horses isn’t just ‘what’ we do, it is ‘how’ and ‘why’ we do it. That understanding is at the foundation of Natural Lifemanship, and it is why we can proudly say, “Yes, we DO ride in therapy!”

References:

Escolas, S.M., Arata-Maiers, R., Hildebrandt, E.J., Maiers, A.J., Mason, S.T., and Baker, M.T. (2012) “The impact of attachment style on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in postdeployed military members.” U.S. Army Medical Department Journal.

Kitagawa, T., Takeuchi, T., Shinomiya, Y., Ishida, K., Shuoyu, W., and Kimura, T. (2001) “Cause of Active Motor Function by Passive Movement.” J. Phys. Ther. Sci. Vol. 13, No. 2, 167-172.

Perry, B.D. and Szalavitz, M. (2006). The boy who was raised as a dog and other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook: What traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. New York: Basic Books.

Siegel, D. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. Bantam.

Siegel, D. (2012) Applications of the Adult Attachment Interview. PESI Publishing & Media

Usadi, E.J., & Levine, S.A. (2017) “Why We Don’t Ride: Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, Military Veterans, and Moral Injury.” Journal of Trauma and Treatment, 6 (2), 1-5

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Aug 7, 2017 | Applied Principles, Basics of Natural Lifemanship

Today is August 7th. August 7th, 2010, Tim and I were married. We had a sunrise wedding at the family ranch in the Texas Panhandle. It was outside on a plateau, overlooking a beautiful canyon, so sunrise was about the only time of day we could lessen the chances of enduring the kinds of winds that blow houses over the rainbow!

We did our first dance horseback to the song “I Run to You” by Lady Antebellum, and I almost fell from Zeus, my trusted steed! We shared a communion of coffee and homemade biscuits with friends and family during the ceremony. We then had tequila sunrises and a delicious chuck wagon breakfast, prepared by a dear friend. The day was perfect!

It is practically impossible to think about our wedding and engagement, without thinking about our business, our first “baby.” The weeks prior to our wedding we built a website, with the help of my brother in law, and started a business. We simply can’t separate ourselves or our relationship from Natural Lifemanship and the idealized belief system at its foundations.

A few years ago, Tim and I wrote the statement you will read below. Natural Lifemanship has grown well beyond the two of us, but these beliefs are the hands that continue to hold us personally and professionally. They are still the touchstone of Natural Lifemanship’s principle-based and process-oriented model of therapy.

We are terribly imperfect at practicing what we believe and what we teach. Tim and I are quite complicated human beings, with all kinds of baggage, and a fly on the wall would attest to how inadequate our best is in the hardest of times. Actually, our closest family and friends can attest to this wholeheartedly, I’m sure.

We are so very different from each other, and there is a rub that doesn’t work each and every moment but does seem to work out most days. So much has changed for us in the last 7 years, but what we believe has not, and our daily choice to try our darndest to care more about relationships than anything else remains.

The statement below is what our certification students agree to before they complete certification in Natural Lifemanship. Today, Tim and I reflect on how these beliefs have affected our relationship, our mission, and our passion, and feel blessed to be part of a community that chooses to attest to such a statement. . . and humbled by the many people whose work and heart have contributed to our mission. . . and by each moment’s grace to change, grow, and, above all, connect.

NL Ethics and Beliefs Statement:

As a person certified in Natural Lifemanship I attest to the following: I believe the most important thing in life is connected, attuned relationships with self and others (including relationship with animals, my Creator as I understand him or her, nature, the universe, etc.) All of life’s healing happens in the context of attuned relationships based on trust, mutual respect, appropriate intimacy, and partnership. I believe strength is found in vulnerability, and that conflict in relationships can be opportunities for growth that can strengthen the relationship. Therefore, regardless of the task or activity, a connected relationship with self and others is always the goal.

I believe that a partnership can happen when each party seeks to control themselves only, and true partnership happens when each party appropriately controls themselves for the good of the relationship. I believe that if it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either and that a one-sided relationship is damaging to both parties.

Regardless of what is going on around me, it is possible to control what is happening inside of me. Relationship with others, quite simply, flows out of the relationship with self (what we sometimes call regulation or my way of being in the world). Therefore, WHO I am is more important than WHAT I do. I realize that I can’t teach someone to do something I can’t do. Likewise, I can’t teach someone to live a life that I don’t live. As a result, personal growth becomes the foundation for ethical therapy. The most important thing is to do my best to do what is right for my client. I understand that what is best may not be what is easiest. In order to do what is right for my clients, I have to know myself – my biases, my blindspots, and at the moment, I have to be connected with my own reactions and impulses so I can filter them. Only then can I do what is actually, truly best for my client. The team approach in NL affords me the opportunity to model a relationship where the NL principles play out and provide a space for the therapy team to notice and discuss biases and blind spots. It is, therefore, my ethical obligation to foster a healthy relationship with my therapy partner. Clinical consultation is a regular part of ethical practice, especially if I am working alone in therapy sessions.

I believe animals are sentient beings, who have relational and thinking capabilities, and can be capable of partnership if given the chance to develop. I believe that a good principle is a good principle regardless of where it is applied. Therefore, all NL principles apply equally to relationship with self and others. The relationship between horse and human is a real relationship in which relational patterns emerge, just like in any other relationship.

When NL certified, I become part of a community of individuals who are deeply committed to connecting with self, connection with others, and who strive for connected relationships the way it was intended. As such, this community of practitioners strives to foster relationships that bring about healing for self, others, and the animal partners with which we work.

by Rebecca Hubbard | May 23, 2017 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Horsemanship

“Isn’t Natural Lifemanship (NL) just joining up?” I hear this question frequently from family, friends and students who are learning Natural Lifemanship. If they know anything about Natural Horsemanship, horse training methods with the intent of developing rapport with a horse based on herd dynamics, they assume that attachment in NL is “joining up.” Since joining up is getting the horse to see you as his leader and to follow you, observers often confuse this with attachment and connection in NL. Attachment can involve having the horse follow you but can also be achieved in many different ways. Further exploration of the process of attachment in NL reveals not only different expectations and beliefs about the process but a different process altogether. The beliefs and intentions of Natural Horsemanship and NL are not the same but both have important places in the world of horses.

In this blog I break down the components of joining up and attachment and compare and contrast them to help students of NL better understand the differences. Joining up and attachment have different purposes. Joining up is an intervention used by men and women (who we will call “trainers”) to train horses using principles from herd dynamics and attachment is part of NL, a psychotherapy model that strives to help humans obtain healthier relationships with themselves and others.

Joining Up is a term that is frequently used in Natural Horsemanship to communicate the process of a horse respecting the trainer as his/her leader. How this is done varies slightly from person to person. Monty Roberts explains it this way:

Working in a round pen, one begins Join-Up® by making large movements and noise as a predator would and begins driving the horse to run away. She then gives the horse the option to flee or Join-Up®. Through body language, the trainer will ask, “Will you pay me the respect due to a herd leader and join and follow me?” The horse will respond with predictable herd behavior: by locking an ear on her, then by licking and chewing and dropping his head in a display of trust. The exchange concludes with the trainer adopting passive body language, turning her back on the horse and without eye contact, invites him to come close. Join-Up occurs when the animal willingly chooses to be with the human and walks toward her accepting her leadership and protection.

From an NL perspective what is involved in this type of joining up? The horse trainer uses the horse’s natural fear of predators and approaches the horse with predator type behavior which frightens the horse and drives the horse into the survival part of his brain causing him to run away from the threat. From the survival part of his brain the horse responds instinctually. When the horse cannot escape the threat, he submits. The change in the trainer’s behavior to less threatening and more passive body language offers possible safety. The horse seeking safety, looks to the trainer for this and begins to ask for permission to approach. When the horseman allows the approach, the horse submits to the trainer as the leader.

Horses are accustomed to being dominated or being the dominant one, so in Join-Up® the interactions reinforce the hierarchy of the herd dynamics. From a horse training perspective this is a much kinder way to get a horse to comply with your requests than to “break” him. From a psychotherapy or NL perspective this interaction is about dominance and control. The horse is not given an option to cooperate because cooperation only occurs when the neocortex (the thinking part of the brain) is engaged and not only the lower regions of the brain. The trainer has all the power in this interaction and though Mr. Roberts uses the word “choice” the horse is not given a choice since he is operating out of the survival parts of his brain. True choices are made from the neocortex.

Let’s look at the above interactions through the lens of human relationships because NL is a psychotherapy model designed to help humans with relationships. A very important principle in NL is “a sound principle is a sound principle no matter where it is applied.” So, in NL we believe that if a principle is sound it will work across different types of relationships. The transfer of these principles is imperative in a therapy model.

When applying the principles from the Natural Horsemanship Join-Up® process to human relationships we see the following: One person has all the control, the relationship is based on a strong, benevolent leader that must be obeyed in order for there to be safety and order. The other person is not allowed to have any control because they may make poor decisions and submission is desired because it is good for the relationship. When viewed within this lens very few people would say that is the type of relationship they want and many would say that it is abusive. Since NL is a psychotherapy model, if we used the Natural Horsemanship principles of Join-Up® we would be teaching people unhealthy ways of relating.

Another very respected natural horseman is Pat Parelli. Like Mr. Roberts he is a well-known and a highly respected horse trainer. In his trainings Mr. Parelli explains how important it is to control a horse’s movement because it raises the trainer’s status to one of leader in the horse’s eyes. In this interaction the trainer is using the herd principle of whoever moves the other’s feet has the status. In this way the person controls the horse by influencing the horse’s feet. Sometimes this involves blocking choices that the horse can make. Sometimes the trainer decides which direction and how fast the horse will go. Leadership is seen as an essential component of the horse and horsemanship relationship. Mr. Parelli notes that if the trainer does not make the decisions then the horse will. Unlike Mr. Roberts, Mr. Parelli does not take the stance of a predator in order to drive the horse away. He uses only the amount of pressure necessary to control the horse’s feet.

When examining these beliefs, we see the following: The trainer controls the horse’s movements and takes away choices as necessary to obtain the horse’s compliance, and the horse cannot appropriately control himself without leadership.

From a human relationship perspective once again one person has all the control and decision making ability as the benevolent leader. The leader controls the other person and limits the choices available to insure appropriate decision making. Like the outcome of Join-Up® these dynamics do not reflect a healthy human relationship pattern.

All of these Natural Horsemanship interactions use operant conditioning, pressure and release, to teach the horse the desired behaviors. NL also uses pressure and release but in a different fashion.

One small part of NL is requesting attachment by applying pressure to the hip of the horse. From the untrained eye this appears similar to Join-Up® or other joining up interactions. There are many significant differences, however.

In NL the intention of every interaction with a horse or human is connection. Submission is seen as an instinctual behavior that the horse or human makes from the survival part of his brain and is undesirable. In order to avoid submission, the trainer/client uses the smallest amount of pressure necessary and abides by the three principles of pressure which are: Ignore- increase, Resist- remain and Cooperate- release and/or decrease.

The process of attachment in NL looks like this. The trainer/client makes a request of the horse in order to begin their relationship. The trainer/client applies pressure to the hip of the horse in order to give the horse the most choice about how to respond (the intent is not to drive the horse). The horse can choose to ignore the request (seem to not notice the request, do nothing in response to the request), resist the request (seek a different answer than the one that is being requested) or cooperate with the request.

Before a request is made the trainer/client must first decide if the request is appropriate, fair, and good for both the trainer/client and the horse. If the request is not good for one of them then it ultimately is not going to be good for the relationship. Each request is made with the smallest amount of pressure possible, usually beginning with just a thought. For example, the thought could be, please look at me. In order to use the smallest amount of pressure the trainer/client must be emotionally regulated and be in control of herself. The trainer/client holds a belief that he/she can only appropriately control himself/herself and the horse can appropriately control himself. If the horse responds to the smallest amount of pressure, then the pressure is released to communicate to the horse, yes that was what I asked for.

However, if the horse ignores the request, that is the trainer/client did not apply enough pressure to convey the request, then the pressure is increased incrementally with warmth and compassion. The decision to increase the pressure incrementally is done so as not to drive the horse into the survival part of his brain and to give the horse the choice to respond with the least amount of pressure possible.

In order to increase the pressure a little the trainer/client may take a deep, long breath to bring up the energy in his/her body while seeing in his/her mind the horse looking at him/her. If the horse responds by looking, the pressure is immediately released. But if the horse responds with a different answer, the trainer/client keeps the pressure the same in order to convey to the horse, that is a nice try but not what I requested.

By keeping the pressure the same the trainer/client does not drive the horse deeper into the survival part of his brain. As the pressure remains the same the horse can come out of the initial survival mode and begin to use his neocortex in attempting to find the answer that the trainer/client requested. The trainer/client keeps the pressure the same as the horse explores what the answer to the request is.

This dance continues until the horse chooses on his own to cooperate with the request. The desire is for the horse to engage his neocortex and to think and to choose connection with the trainer/client. If the horse submits instead of cooperating, then the trainer/client knows that he/she increased the pressure during resistance (hunting an answer). This is an undesirable outcome and the dance begins again with the smallest amount of pressure until cooperation is achieved from the horse’s neocortex.

The dance of asking the horse to follow is built on scaffolding of the requests. It may start out with the request for an ear, or an eye then move to a whole head turn, then the horse’s body turning to face the trainer/client, then the horse making a step toward the trainer/client and lastly them taking a walk together. The request to walk together is made out of a desire for connection and not to be the leader of the horse.

If we examine attachment and these steps of getting a horse to follow through the lens of a human relationship, we find respectful requests made with warmth and compassion, allowance and respect for another’s choice, a genuine desire to connect, acceptance of the other’s response, compassion and warmth in helping them find the right answer to the request, and a respect for and allowance of the thinking process and autonomy of another. In this process the trainer/client and horse are equal partners, each brings strengths and weakness to the partnership. This would be the same for all relationships, such as couples and friendships.

When the intention and principles behind the processes of attachment in NL and joining up in Natural Horsemanship are fully examined, attachment in NL is very different from Join-Up® or joining up in Natural Horsemanship. Remember, in NL there are infinite ways to ask for attachment, putting pressure on the hip is just one of them. Attachment can be requested any number of ways, and how it is asked depends on creativity and attunement in the relationship.

Recent Comments