The 5 Steps for Repair in a Relationship

By Bettina Shultz-Jobe

I recently wrote a blog about how we can build strong connections with ourselves and others through rupture and repair. Many of us have not had healthy rupture and repair modeled in our lives and are, therefore, just beginning the journey of embracing this practice and this way of being in the world, so I thought it might be helpful to discuss some actionable steps we can take when seeking repair in a relationship.

Oftentimes, people use the terms “repair” and “apology” synonymously. An apology is not a repair. It is merely a part of what is needed to make a repair. Let’s discuss the most basic components of a repair, while also holding the awareness that putting steps to a process that involves human relationships (that can be quite complicated!) will always be an oversimplification. Hopefully, still useful, but an oversimplification, nonetheless.

Repair requires attunement and a deep acceptance that life and relationships are not “black and white” and perfection is never the goal. Relationships are messy and re-connection is always the goal during a relational repair and during conflict resolution.

Step 1: Allow Guilt, Reject Shame

Shame says, “I am a bad person.” Guilt says, “I did a bad thing.”

Research shows that when we feel shame, we become defensive, deny, blame others, and oftentimes, get angry at others for making us feel this way, but what we don’t do is change our behavior. When we feel shame we struggle to accept how our behavior affected someone else because it’s far too painful to think “I’m a horrible person.”

Shame is a self-focused emotion, “Me, me, me. . . I’m such a horrible person. What are you thinking of me? Are you thinking I’m a horrible person too?” When we struggle to distinguish between what I do and who I am, we move into a shame spiral, and repair becomes almost impossible.

Shame often has roots in our earliest experiences with caregivers. It may feel inherent to who you are, but that younger version of you can be nurtured into letting go of these shame messages.

Conversely, appropriate guilt is what is needed if we are to offer repair in relationships. Research shows that guilt allows us to focus on what we’ve done. Behavior is easier to change than self so when we feel guilt about a specific behavior, we are more likely to feel empathy for the person we’ve hurt. We are, therefore, more inclined to want to apologize and make things right. Acceptance of appropriate guilt – “I made a bad choice and that hurt your feelings” – is needed in order to do each of the following steps for repair.

Step 1 is about self-compassion.

“I am a good person, and I made a poor choice. My choice caused a rupture in this relationship, but I know that I can make it right. I can make a repair.” It is during this step that you can seek to understand why you did what you did without making excuses.

Feeling guilt instead of shame is very difficult for many of us, especially those of us who have survived childhood trauma, because the ability to distinguish between what I do and who I am does not emerge before the age of approximately seven or eight. This is one of the reasons that punitive child rearing can have grave effects on the development of the self. Child abuse and neglect often result in an adult who can feel shame, but not guilt. If you are struggling in this area, I encourage you to seek out counseling services with someone who specializes in complex trauma.

Step 2: Listen

Listen deeply and completely so that you can fully understand the damage that was done. Allow the other to be heard without defending or explaining yourself. Remember, the goal of conflict resolution is not to be right or to make a point, it is to repair by reconnecting. This step is for deeply understanding how your actions affected the person in front of you.

Laura Trevelyan, who was an anchor and correspondent for BBC News, and currently campaigns for reparative justice in a full-time capacity, puts it this way, “When seeking repair, the more you expose yourself to the full sensory experience of whoever’s been harmed, the closer you are to finding the right next step.”

I love this! Listen so deeply, that you “expose yourself to the full sensory experience” of whoever you have hurt.

This step is about profound empathy and deep compassion for the other.

Step 3: Apologize

Sincerely apologize for what you have done to damage the relationship. It is important that you explicitly state “I’m sorry. . . .” or “I apologize. . .” and expand on exactly what you are sorry for. Provide details about the situation, acknowledge your role in the situation, and repeat, in your words, how your actions have affected them. It is possible that you may need to return to step two, if the person you have hurt needs to clarify how your decisions affected them. Avoid phrases like, “I’m sorry you felt hurt” or “sorry if” or “sorry but” – these are all ways of minimizing the damage done.

Lastly, ask for forgiveness, and do not assume they will forgive you right away. Remember, forgiveness itself is a very personal process that can beautifully unfold during steps 4 and 5.

The apology is very important, but it is not the repair. Apologies without repair, over and over again, will undermine trust in the apology and in the integrity of the person offering the apology.

Step 4: Make Amends

Mend what was broken.

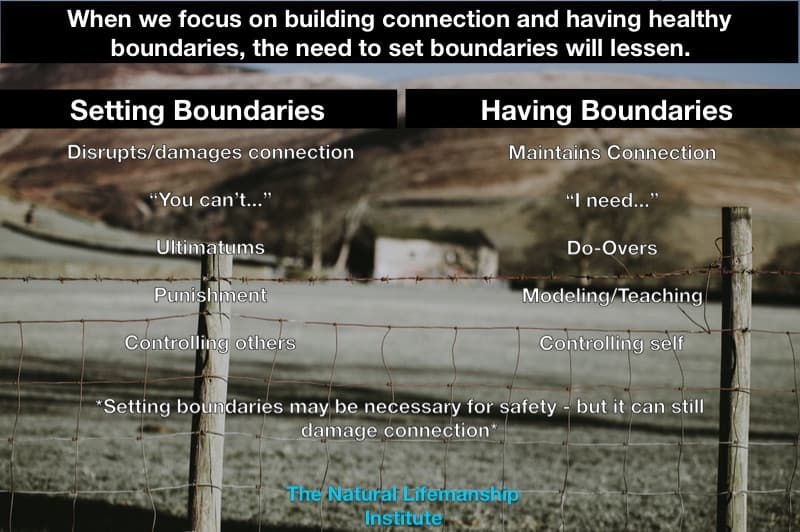

In this step you consider what you can do to right the wrong. One of my favorite ways to make a repair is to do what we often call a do-over or a rewind. In a do-over, you literally play the entire situation again and get the opportunity to do it differently. This step is so powerful and so often missed. I wrote a short blog to breathe life into what we mean by do-overs with this personal story.

The “rewind” is a similar concept that Tim and I have used quite a bit in our marriage. I will often make the sound of a tape rewinding (yes, I know I’m dating myself!) and then say something to this effect, “When you said ______, I really wish I had said _______. Would you give me the opportunity to go back to that moment and make a different choice?”

(I should add that the sound of the tape rewinding is lovely only if a bit of humor could bring some lightness to the conversation. As with all humor, definitely use it with caution.)

The rewind and the do-over empower us to practice and embody the change we hope to make in the future, and in the present moment both parties get to experience something different, rather than just imagine a different, hypothetical future.

Step 5: Continually Foster Reparative Experiences

Much of the time, mending what was broken in a relationship is not a one time event but a process that takes time. In situations where the rupture was large and/or took place over and over again (with little to no repair), each step in this process will also need to happen over and over again.

For example, when there has been infidelity in a relationship, each partner will need to choose to repeatedly do things differently, offering reparative experiences through every interaction to rebuild trust and connection.

At times, we might need to acknowledge that a situation feels like the one that led to the rupture in the first place and then overtly offer the reparative experience. “I can understand how this moment might feel a lot like the situation in which I caused you so much pain and heartbreak. This moment is different because I’m trying to [insert reparative behavior], and I am committed to you and to this relationship, and to the promises I made when we first started working to repair our relationship.”

Repair with a child

When repairing a relationship with a child, try something like this: “I know in the past when things like this happened, I didn’t listen and I punished you. Right now, I am here and I am listening, and we are going to work this out together. I am going to do what I have promised, what I have committed to you and to our relationship.”

Repair in sessions with clients

In sessions with clients, here’s one approach: “I know in the past when a big emotion came up for you, you needed to hide and work it out for yourself. Today you are not alone. I am here and I am okay with the expression of whatever emotion you may have. You don’t need to hide or suppress or get over it by yourself. I am here to listen and offer support.”

A repair is more than an apology. A repair has to be experienced. It has to be lived. It’s an opportunity to practice doing the right thing for the relationship. Practice does not make perfect, but it is certainly required for improvement and growth. It is through the embracing of repair, over and over again, that we can accept that ruptures will happen and that the world will not end.

When we are no longer scared of ruptures, we can be free to try, to show up, and to be willing to make mistakes.

As a community, I invite all of us to commit to practicing repair. The kind of repair that moves beyond an apology, and means that we vulnerably go back and try again. This kind of repair requires grace and commitment to connection from all involved – grace that provides space for do-overs, rewinds, repair, and real healing. Deep, complete healing and profound, transformative connection.

When Olive came to live with us, I spent the first few weeks feeling totally overwhelmed. I had had dogs all my life, but she was a conundrum. How can a dog be so selfish, so uninterested in my requests, so hard to soothe? Then, after too long, it hit me…duh, I have a dog with her own difficulties of attachment trauma. I had been studying this and working with families who struggled with this for several years now – but it only then occurred to me that my dog might be experiencing the same thing (it’s so easy to compartmentalize humans as being totally different from animals…but really, that’s just not the case that often). Thankfully, a light bulb went on about so many of her behaviors. For example:

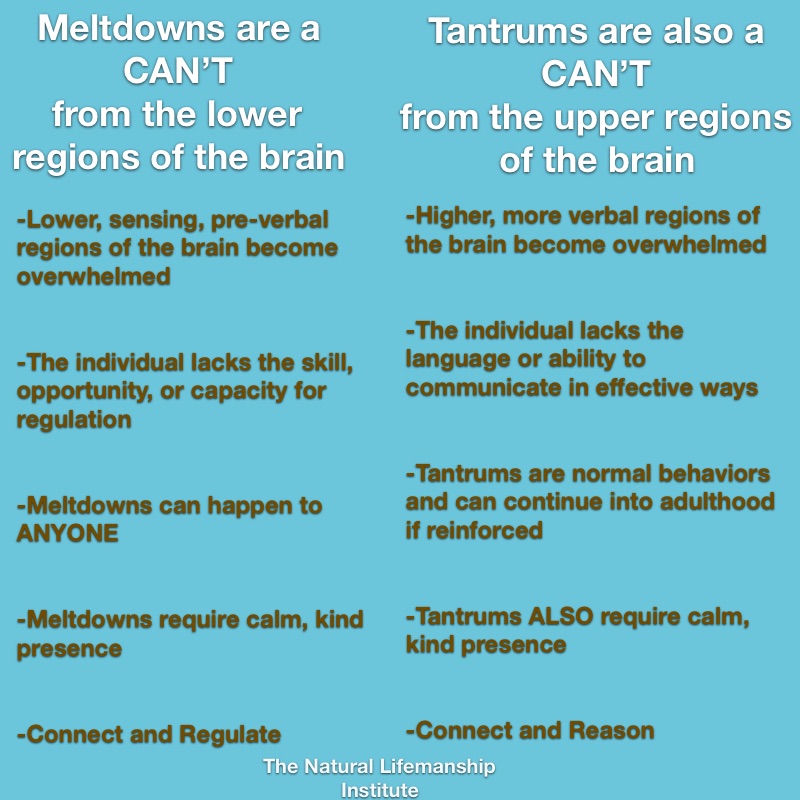

When Olive came to live with us, I spent the first few weeks feeling totally overwhelmed. I had had dogs all my life, but she was a conundrum. How can a dog be so selfish, so uninterested in my requests, so hard to soothe? Then, after too long, it hit me…duh, I have a dog with her own difficulties of attachment trauma. I had been studying this and working with families who struggled with this for several years now – but it only then occurred to me that my dog might be experiencing the same thing (it’s so easy to compartmentalize humans as being totally different from animals…but really, that’s just not the case that often). Thankfully, a light bulb went on about so many of her behaviors. For example: Imagine trying to ride a bike down a mountain path, when it’s your first time on a bike! You would totally fail – not because you didn’t care, but because you didn’t have the previous experience as a foundation for this new one. Neural pathways don’t change simply because circumstances change, they change over time, with practice and consistency. Just like learning to ride a bike.

Imagine trying to ride a bike down a mountain path, when it’s your first time on a bike! You would totally fail – not because you didn’t care, but because you didn’t have the previous experience as a foundation for this new one. Neural pathways don’t change simply because circumstances change, they change over time, with practice and consistency. Just like learning to ride a bike.

Recent Comments