By Kathleen Choe and Tanner Jobe

Recently, Tanner and I had an experience in an Equine Assisted Psychotherapy session where we had planned to do trauma processing with our client using Equine Connected Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EC-EMDR) which is essentially EMDR while mounted on a horse, where the movement of the horse provides Dual Attention Stimulus as well as relational connection for the client. The problem was, our equine therapy partner, Gretta, was having a great deal of trouble with connection that day. Prior to the start of the session, Tanner spent an hour in the pasture with her, asking her to connect, which she eventually did while at liberty, but when he asked her to halter with connection, she alternated between dissociating and submitting, or resisting by pulling her head away or walking off.

When the client arrived, I went to greet her at the cabin where we begin our sessions with a check in, leaving Tanner in the pasture with Gretta, assuming he would arrive at the round pen shortly with Gretta in tow. After half an hour of talking with the client about her transfers of learning from the previous session and what our therapeutic goals were for the current one, I noticed that Tanner and Gretta still had not appeared. I knew the client was eager to do trauma processing that day and had come prepared with a particular memory she had targeted to work on. I stepped out of the cabin and called to Tanner, asking him if he would be bringing Gretta soon (as in, now!). He called back that we would have to come to the pasture. I immediately felt both awkward and annoyed, awkward towards the client, who was ready to go with the mounted work we had planned on doing, and annoyed with Tanner for not just settling for an ear flick or eye ball’s worth of connection so that he could halter Gretta in good conscience and cooperate with our agenda for today’s session.

As we walked to the pasture, I found myself nervously re-summarizing to the client the importance of the principles of choice and mutual partnership in building relationships, including for the horse, principles we had introduced and then affirmed repeatedly throughout the course of the therapy thus far, explaining the damage that would be done to our relationship with Gretta if we forced her to submit to being haltered and led to the round pen instead of asking for her cooperation in participating in the session. I was saying all the “right words” consistent with the principles of Natural Lifemanship, but inwardly I was struggling with concern for failing the client’s expectations and not meeting the client’s needs. My professional values of delivering a quality product and following through on commitment clashed with what I viewed as Tanner’s puritanical insistence that we wait for Gretta to choose to cooperate. As we walked through the gate into the pasture it began to rain. Tanner was standing next to Gretta holding out the halter calmly and patiently. Gretta looked tense with a determined set to her jaw. Surveying the scene, I was tense and angry, inwardly hissing at Tanner to just put the damn halter on and be done with it! Gretta’s nose was centimeters away from the noseband. So close!

I took a deep breath and decided to let Tanner explain to the client why she wasn’t going to be doing mounted trauma processing that day. As the rain slid down my already chilly neck, I morosely pictured this client terminating future sessions and walking away from EAP in frustration.

Tanner asked the client how Gretta seemed to be feeling about being haltered today. (“Not that bad,” I thought). The client observed that Gretta seemed anxious every time Tanner offered the halter to her.

“What would happen if I just put it on anyway?” he asked her. (“Nothing!” I screamed inside. “She would just stand there and let you do it!”)

The client thought a moment, then said, “She would probably let you do it, but it wouldn’t feel good to her on the inside.”

“How would it affect our relationship then?” Tanner continued.

“She would feel used,” the client responded. Then she continued, “I do that. I just want a certain outcome so I get impatient and push forward no matter what the other person is showing me they feel about it.”

Standing there in the rain, watching my client fully grasp what was happening between Gretta and Tanner, and applying it to her own life and style of relating, I felt the fallacy of my product-oriented, outcome-focused style of therapy come crashing down around me.

Yes, Tanner could have simply buckled the halter on Gretta and she probably would have followed him out of the pasture to the round pen, let us put on a bareback pad and then the client on her back, and walked around in circles behind Tanner while the client processed her traumatic memory. The client might even have felt some relief from the toxic emotions embedded in her experience. However, in approaching the session this way, sticking to our plan despite the clear feedback from a vital member of the therapy team, we would have violated the basic tenets of the Natural Lifemanship model of EAP: building an attuned, connected relationship is the goal of any interaction, and that this is the kind of good, healthy relationship that is the vehicle for healing and change. Gretta would have become a glorified rocking chair, a vehicle for carrying the client, reduced to a tool. Objectifying and instrumentalizing Gretta in this way would have modeled for the client that is o.k. to sometimes “use” others in the service of our recovery, that there are situations where the “higher good” of the outcome justifies the means employed to get there.

Not only Gretta’s welfare would have been compromised, however. The client’s potential for true, deeper healing would have been affected as well. Without the relational connection between the client and the one who carries her, the limbic system would not be engaged in a manner that promotes re-wiring of the faulty neural pathways wired around the trauma to grow new neuronal pathways of trust and growth. Gretta would have been left without even a connection to her horse professional, much less her rider. Her pathways for dissociation and compliance would be strengthened, making it much harder for her to trust offers of choice and connection in the future, and the client’s pathways for being controlled by or controlling others would unhappily be strengthened as well.

I called Laura (the director of education and research for NL) after the session, expressing concern about how the client might have perceived the experience, and her potential disappointment and frustration that she wasn’t able to process her trauma target that day. I shared my fears that I was compromising my professional responsibilities and explained that even when I’m having a bad day I have to show up for the client and attend to their needs, no matter how or what I’m feeling, despite the hard things that may be going on in my personal life. The therapeutic relationship is somewhat one-sided between counselor and client in that the counselor does not ask the client to meet her needs in the same way one might in a personal relationship. Laura pointed out that I have a choice about whether to conduct sessions when my personal life is in crisis, and that if I choose to meet with a client I’m deciding to put aside my personal struggles to attend to theirs. If our equine therapy partners are not able to make these choices in the same manner then how are we being congruent with our inherent belief that they are equal members of a team based on mutual partnership and cooperation? (In other words, Laura agreed with Tanner!)

In processing the session afterwards, Tanner and I discussed the importance of having alternative methods of trauma processing to offer the client should the equine partner not be able to participate in mounted work in a relationally connected manner on any given day, rather than trying to stick to the original plan, which would ultimately be at the expense of both client and horse. We could have the client walk beside the horse, perhaps touching her side as they walk together, or do traditional EMDR using eye movements or tappers, or employ other somatic interventions like drumming to provide the Dual Attention Stimulus and grounding involved in effective processing. Introducing these concepts at the beginning of the therapy process so the client understands that the course of the session will be dependent on what is actually happening relationally in the present rather than being defined by a pre-determined agenda will be key to developing a shared understanding of how Equine Assisted Psychotherapy true to the Natural Lifemanship model actually works.

Tanner’s Point of View

I had been working with Kathleen as her equine professional in therapy sessions for a couple of months. The person she had been partnering with previously went on maternity leave so I was filling in for sessions that were already in progress – basically, entering the process of therapy at some point other than the beginning. This provided many initial challenges. First, Kathleen had already built rapport and established a therapeutic relationship with the client and I was replacing someone who had also done the same. Second, I was working with Kathleen in therapy for the first time ever. We already had a relationship as NL trainers and had worked together in that capacity but had never actually worked together in therapy sessions. Third, I was working at an equine facility I had never visited before and was partnering with horses I had never met prior to these therapy sessions. Another part of that challenge was that I was only doing two sessions on Tuesday mornings at this facility and balancing that with a mountain of other responsibilities for Natural Lifemanship. I really did not have the time I would have preferred to meet and build relationships with the horses we would be partnering with in therapy sessions. (I know others can relate to this!) I would have to build these relationships as therapy sessions progressed and do so in a way that did not disrupt the process for the client. Furthermore, I had very little knowledge about the relationship patterns that the horses had developed from their interactions with various people on a daily basis and if those people were aligned with me and NL philosophically. I just wasn’t sure what the horses were learning about relationships outside of their interactions with me. I did not “own” these horses and I did not care for them daily, and I knew it was not reasonable for me to expect those who did to suddenly change their interactions based on my philosophy. Again, I know others can relate. Nonetheless, the proof of the pudding is in the eating, so with all of these things in mind I began the process of working with Kathleen as part of the therapy team with the intention to take it as it comes and simply do my best to adapt and learn.

The transition into sessions went fairly smoothly and soon I was starting to learn about our client as well as the horses involved in our sessions. I was told that Gretta was the horse they had been partnering with for mounted work and went out to get her for one of our first sessions. I immediately noticed that Gretta was uncomfortable with my presence. She was tense in the ears, face, and eyes. When I said hello and asked her to engage, she maintained the tension and did her best to ignore my request for minimal attention. I found that I could walk right up to her and she was not threatening but she also would not really engage with me. I could touch her and she did not seem to change, respond, or react. She did not clearly say yes or no. She would even let me halter her. She did pull her head away slightly but not emphatically. It seemed as though she did not want anything to do with me but also did not expend any energy to get away from me. In my error, not knowing Gretta at all and only operating off of information from others and my own assumptions from that information, I put her halter on and led her out of the paddock. Throughout that morning’s interactions I learned a lot about Gretta. She disconnected and tried to eat grass at every opportunity. She was touchy around her girth and even grooming there caused her to pin her ears and nip at me. Tightening the girth of the bareback pad resulted in her attempting to bite me. Nonetheless, I gently did my best to push through all of these standard processes that a horse goes through in preparation for mounted work and started to lead her to the round pen. Leading her further away from the paddocks and barn to a round pen that was a little more remote, I noticed her anxiety increase significantly. She walked fast and out in front of me attempting to drag me along. Her head shot down to feverishly eat grass at every opportunity (one of her attempts to regulate). Her head would shoot up and ears and eyes harden as she looked at the round pen by the therapy cabin where we were to do our work for the morning. I stayed calm and continued to ask her to be aware of me and to walk without stepping on me as we moved to the round pen. When we entered the round pen, I removed the lead rope from her halter and she immediately trotted away investigating the round pen with an anxious energy. When I put a little pressure on her back hip and asked that she engage with me she appeared agitated and maybe even a bit angry. She pinned her ears and bucked and kicked and galloped around the pen. I did what I know to do and kept the pressure the same while staying calm and relational until she was able to connect and attach (follow me while calm, present, and connected). Then I asked her to detach (move way) and received the same anxious, aggressive response. I helped her calm down and engage through detachment and then asked her to reattach. When she was able to detach while remaining connected I reattached the lead rope and mounted. I wanted to make sure she was safe to ride. She proved to be ok but she was clearly still full of anxiety. However, the client had arrived and was waiting with Kathleen outside of the pen so that we could start her session. I decided this had to be good enough and we proceeded with the therapy session. We had the client mount and we started moving in a circle with me leading Gretta. At one point I remember the sun umbrella on the deck of the cabin suddenly falling over and spooking Gretta. She jumped sideways and almost lost our client but I was able to get her to stop. Gretta was obviously anxious and on edge the entire session – as we got to a certain section of the pen she would worry about something that was out in the trees. She would speed up and at times trot ahead of me as we passed this section of the pen. It was a stressful session for me as I had to do a lot of work trying to make sure Gretta was not going to hurt our client. I did not like having to manage all of that. I knew Gretta and I had a lot of work to do moving forward.

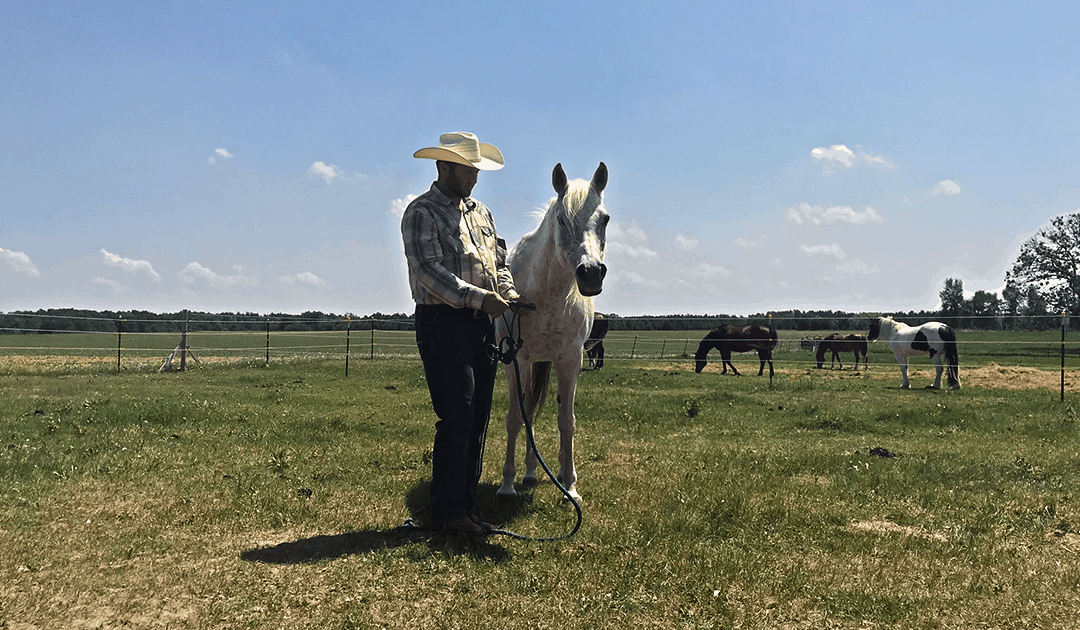

I made a lot of mistakes that first session and I took note of what I needed to improve and I started showing up at least an hour early for our sessions so that I could spend the appropriate amount of time connecting with Gretta and making sure I got true consent from her every step of the way before asking her to carry our client. I started really making sure Gretta was present when I made a request and that I was attuned to the emotions she felt around each request that I made. Typically, I would show up with the halter to bring her in and we would spend around 30 minutes in the paddock simply getting to the place in which she could look at me calmly, without anxiety, and then follow me at liberty while being fully present. I would offer the halter and wait for her to give me a clear yes and then proceed through the process of grooming and saddling and mounting with the same attuned concern for our relationship and her willful participation in the session. Her overall anxiety was starting to go down and things were improving steadily though she still seemed to be generally grumpy (and maybe even a little pissed) about being asked to do anything. It seemed to me that she typically felt lots of strong feelings in her daily life and just pushed them down and held them in – appeased, submitted, and dissociated. (Check out these two blogs to better understand dissociation with horses: When Dissociation Looks Like Cooperation or Six Signs Your Horse May be Dissociating or Submitting Rather than Choosing to Connect) When I would ask her to truly communicate with me how she felt about doing the things I was asking, it seemed I was the target of pent up aggression that she felt much of the time when I was not with her. Every morning an hour before session Gretta and I would work on this. It did not at all feel fair to me. I had no way of knowing if these outbursts towards me were a symptom of her daily life or a symptom of our relationship. What I did know, is that no matter what, I would have to be committed to doing the work to help her be less aggressive and more connected and I would have to do it slowly in that one hour before sessions on Tuesday mornings because that is all the time I could afford to spend with her. I would have to be happy taking improvements slowly as they came in hopes that the one hour I spent with Gretta each week, or every other week, would be enough to affect real change in her pattern of relating. Sound familiar? So I was committed to the relationship with Gretta and this is where we return to the morning that Kathleen arrives to discover me still asking Gretta to consent to the halter. (Can Animals Consent? – check out this blog on the subject)

It was a cold rainy day. The paddock had big sloppy hoof-shaped mud holes stomped out of it in the places where the horses preferred to gather around the round bale. It was not pleasurable to be out in the light mist trying to catch a horse for a therapy session that might not happen if it started raining any harder. So feeling some stress of my own I set out following Gretta through the mud and rain as she resisted basic engagement with me as usual. I stayed committed to our relationship – it seemed as though Gretta was begging me to take control of her – I refused.

At some point, Kathleen showed up and checked in on us. She watched for a bit and then had to return to the cabin to meet our client when she showed up. When the client arrived, she and Kathleen noticed me in virtually the same place with Gretta trying to resist and then comply but never really connecting with me. It started raining a little bit harder and Gretta was smart enough to move underneath the shed in the paddock. She would connect a little and follow me, then disconnect and resist and return to the shed where she would then reconnect with me. She seemed to be smart enough to want to continue this process out of the rain. I was happy to oblige. So. . . we were under the shed and were staying pretty connected and had progressed to working on accepting the halter. Gretta would get stark still and then try to check out (dissociate). I would ask her to reconnect and offer the halter and she would pull her head away showing tension in her ears and eyes and muzzle. I was acutely aware that our client had arrived and that I clearly did not have a horse prepared for mounted work. I expected Kathleen would have some other options and would arrive with the client to help her become a part of this process and that we would follow Gretta’s lead today. I was aware of my frustration and was consciously releasing the tension it caused in my body as I worked through this process with Gretta. Kathleen eventually emerged from the cabin asking if we were going to be ready soon. I was frustrated with this question as I thought it was pretty obvious that I could not give any definite answers to that question. Kathleen was polite but I could tell there was some tension and anxiety that accompanied the question. I suggested that she bring the client out so she could be a part of the process. Okay, so I basically suggested that Kathleen change the clinical plan for the session because the horse had not consented to participate.

It was not a comfortable feeling but I was not willing to accept compliance from Gretta, our client’s therapy partner. I was also keenly aware that I did not want to be responsible for the safety of a client on a horse who was anxious and had not consented to the halter and had certainly not consented to being ridden. The beauty of the situation is that both Kathleen and I were feeling some stress, pressure and anxiety, but were both able to regulate, relate, and reason so the session turned out to be beneficial for both horse and client. Remember, if it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either, and true healing cannot happen at the expense of another. This work is about connection and relationship – for the client AND horse.

In a perfect world, after that first session with Gretta, I would have set aside loads of time for us to work on lots and lots of stuff before she resumed mounted work in therapy sessions. We all did our best in the moment and tried to adapt and change and grow. We continue down that path.

Tanner and Kathleen are both NL trainers and will be teaching at the 2019 NL Conference. Check it out!

Recent Comments