by Kathleen Choe | Aug 29, 2019 | Case Studies, Horsemanship

By Kathleen Choe and Tanner Jobe

Recently, Tanner and I had an experience in an Equine Assisted Psychotherapy session where we had planned to do trauma processing with our client using Equine Connected Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EC-EMDR) which is essentially EMDR while mounted on a horse, where the movement of the horse provides Dual Attention Stimulus as well as relational connection for the client. The problem was, our equine therapy partner, Gretta, was having a great deal of trouble with connection that day. Prior to the start of the session, Tanner spent an hour in the pasture with her, asking her to connect, which she eventually did while at liberty, but when he asked her to halter with connection, she alternated between dissociating and submitting, or resisting by pulling her head away or walking off.

When the client arrived, I went to greet her at the cabin where we begin our sessions with a check in, leaving Tanner in the pasture with Gretta, assuming he would arrive at the round pen shortly with Gretta in tow. After half an hour of talking with the client about her transfers of learning from the previous session and what our therapeutic goals were for the current one, I noticed that Tanner and Gretta still had not appeared. I knew the client was eager to do trauma processing that day and had come prepared with a particular memory she had targeted to work on. I stepped out of the cabin and called to Tanner, asking him if he would be bringing Gretta soon (as in, now!). He called back that we would have to come to the pasture. I immediately felt both awkward and annoyed, awkward towards the client, who was ready to go with the mounted work we had planned on doing, and annoyed with Tanner for not just settling for an ear flick or eye ball’s worth of connection so that he could halter Gretta in good conscience and cooperate with our agenda for today’s session.

As we walked to the pasture, I found myself nervously re-summarizing to the client the importance of the principles of choice and mutual partnership in building relationships, including for the horse, principles we had introduced and then affirmed repeatedly throughout the course of the therapy thus far, explaining the damage that would be done to our relationship with Gretta if we forced her to submit to being haltered and led to the round pen instead of asking for her cooperation in participating in the session. I was saying all the “right words” consistent with the principles of Natural Lifemanship, but inwardly I was struggling with concern for failing the client’s expectations and not meeting the client’s needs. My professional values of delivering a quality product and following through on commitment clashed with what I viewed as Tanner’s puritanical insistence that we wait for Gretta to choose to cooperate. As we walked through the gate into the pasture it began to rain. Tanner was standing next to Gretta holding out the halter calmly and patiently. Gretta looked tense with a determined set to her jaw. Surveying the scene, I was tense and angry, inwardly hissing at Tanner to just put the damn halter on and be done with it! Gretta’s nose was centimeters away from the noseband. So close!

I took a deep breath and decided to let Tanner explain to the client why she wasn’t going to be doing mounted trauma processing that day. As the rain slid down my already chilly neck, I morosely pictured this client terminating future sessions and walking away from EAP in frustration.

Tanner asked the client how Gretta seemed to be feeling about being haltered today. (“Not that bad,” I thought). The client observed that Gretta seemed anxious every time Tanner offered the halter to her.

“What would happen if I just put it on anyway?” he asked her. (“Nothing!” I screamed inside. “She would just stand there and let you do it!”)

The client thought a moment, then said, “She would probably let you do it, but it wouldn’t feel good to her on the inside.”

“How would it affect our relationship then?” Tanner continued.

“She would feel used,” the client responded. Then she continued, “I do that. I just want a certain outcome so I get impatient and push forward no matter what the other person is showing me they feel about it.”

Standing there in the rain, watching my client fully grasp what was happening between Gretta and Tanner, and applying it to her own life and style of relating, I felt the fallacy of my product-oriented, outcome-focused style of therapy come crashing down around me.

Yes, Tanner could have simply buckled the halter on Gretta and she probably would have followed him out of the pasture to the round pen, let us put on a bareback pad and then the client on her back, and walked around in circles behind Tanner while the client processed her traumatic memory. The client might even have felt some relief from the toxic emotions embedded in her experience. However, in approaching the session this way, sticking to our plan despite the clear feedback from a vital member of the therapy team, we would have violated the basic tenets of the Natural Lifemanship model of EAP: building an attuned, connected relationship is the goal of any interaction, and that this is the kind of good, healthy relationship that is the vehicle for healing and change. Gretta would have become a glorified rocking chair, a vehicle for carrying the client, reduced to a tool. Objectifying and instrumentalizing Gretta in this way would have modeled for the client that is o.k. to sometimes “use” others in the service of our recovery, that there are situations where the “higher good” of the outcome justifies the means employed to get there.

Not only Gretta’s welfare would have been compromised, however. The client’s potential for true, deeper healing would have been affected as well. Without the relational connection between the client and the one who carries her, the limbic system would not be engaged in a manner that promotes re-wiring of the faulty neural pathways wired around the trauma to grow new neuronal pathways of trust and growth. Gretta would have been left without even a connection to her horse professional, much less her rider. Her pathways for dissociation and compliance would be strengthened, making it much harder for her to trust offers of choice and connection in the future, and the client’s pathways for being controlled by or controlling others would unhappily be strengthened as well.

I called Laura (the director of education and research for NL) after the session, expressing concern about how the client might have perceived the experience, and her potential disappointment and frustration that she wasn’t able to process her trauma target that day. I shared my fears that I was compromising my professional responsibilities and explained that even when I’m having a bad day I have to show up for the client and attend to their needs, no matter how or what I’m feeling, despite the hard things that may be going on in my personal life. The therapeutic relationship is somewhat one-sided between counselor and client in that the counselor does not ask the client to meet her needs in the same way one might in a personal relationship. Laura pointed out that I have a choice about whether to conduct sessions when my personal life is in crisis, and that if I choose to meet with a client I’m deciding to put aside my personal struggles to attend to theirs. If our equine therapy partners are not able to make these choices in the same manner then how are we being congruent with our inherent belief that they are equal members of a team based on mutual partnership and cooperation? (In other words, Laura agreed with Tanner!)

In processing the session afterwards, Tanner and I discussed the importance of having alternative methods of trauma processing to offer the client should the equine partner not be able to participate in mounted work in a relationally connected manner on any given day, rather than trying to stick to the original plan, which would ultimately be at the expense of both client and horse. We could have the client walk beside the horse, perhaps touching her side as they walk together, or do traditional EMDR using eye movements or tappers, or employ other somatic interventions like drumming to provide the Dual Attention Stimulus and grounding involved in effective processing. Introducing these concepts at the beginning of the therapy process so the client understands that the course of the session will be dependent on what is actually happening relationally in the present rather than being defined by a pre-determined agenda will be key to developing a shared understanding of how Equine Assisted Psychotherapy true to the Natural Lifemanship model actually works.

Tanner’s Point of View

I had been working with Kathleen as her equine professional in therapy sessions for a couple of months. The person she had been partnering with previously went on maternity leave so I was filling in for sessions that were already in progress – basically, entering the process of therapy at some point other than the beginning. This provided many initial challenges. First, Kathleen had already built rapport and established a therapeutic relationship with the client and I was replacing someone who had also done the same. Second, I was working with Kathleen in therapy for the first time ever. We already had a relationship as NL trainers and had worked together in that capacity but had never actually worked together in therapy sessions. Third, I was working at an equine facility I had never visited before and was partnering with horses I had never met prior to these therapy sessions. Another part of that challenge was that I was only doing two sessions on Tuesday mornings at this facility and balancing that with a mountain of other responsibilities for Natural Lifemanship. I really did not have the time I would have preferred to meet and build relationships with the horses we would be partnering with in therapy sessions. (I know others can relate to this!) I would have to build these relationships as therapy sessions progressed and do so in a way that did not disrupt the process for the client. Furthermore, I had very little knowledge about the relationship patterns that the horses had developed from their interactions with various people on a daily basis and if those people were aligned with me and NL philosophically. I just wasn’t sure what the horses were learning about relationships outside of their interactions with me. I did not “own” these horses and I did not care for them daily, and I knew it was not reasonable for me to expect those who did to suddenly change their interactions based on my philosophy. Again, I know others can relate. Nonetheless, the proof of the pudding is in the eating, so with all of these things in mind I began the process of working with Kathleen as part of the therapy team with the intention to take it as it comes and simply do my best to adapt and learn.

The transition into sessions went fairly smoothly and soon I was starting to learn about our client as well as the horses involved in our sessions. I was told that Gretta was the horse they had been partnering with for mounted work and went out to get her for one of our first sessions. I immediately noticed that Gretta was uncomfortable with my presence. She was tense in the ears, face, and eyes. When I said hello and asked her to engage, she maintained the tension and did her best to ignore my request for minimal attention. I found that I could walk right up to her and she was not threatening but she also would not really engage with me. I could touch her and she did not seem to change, respond, or react. She did not clearly say yes or no. She would even let me halter her. She did pull her head away slightly but not emphatically. It seemed as though she did not want anything to do with me but also did not expend any energy to get away from me. In my error, not knowing Gretta at all and only operating off of information from others and my own assumptions from that information, I put her halter on and led her out of the paddock. Throughout that morning’s interactions I learned a lot about Gretta. She disconnected and tried to eat grass at every opportunity. She was touchy around her girth and even grooming there caused her to pin her ears and nip at me. Tightening the girth of the bareback pad resulted in her attempting to bite me. Nonetheless, I gently did my best to push through all of these standard processes that a horse goes through in preparation for mounted work and started to lead her to the round pen. Leading her further away from the paddocks and barn to a round pen that was a little more remote, I noticed her anxiety increase significantly. She walked fast and out in front of me attempting to drag me along. Her head shot down to feverishly eat grass at every opportunity (one of her attempts to regulate). Her head would shoot up and ears and eyes harden as she looked at the round pen by the therapy cabin where we were to do our work for the morning. I stayed calm and continued to ask her to be aware of me and to walk without stepping on me as we moved to the round pen. When we entered the round pen, I removed the lead rope from her halter and she immediately trotted away investigating the round pen with an anxious energy. When I put a little pressure on her back hip and asked that she engage with me she appeared agitated and maybe even a bit angry. She pinned her ears and bucked and kicked and galloped around the pen. I did what I know to do and kept the pressure the same while staying calm and relational until she was able to connect and attach (follow me while calm, present, and connected). Then I asked her to detach (move way) and received the same anxious, aggressive response. I helped her calm down and engage through detachment and then asked her to reattach. When she was able to detach while remaining connected I reattached the lead rope and mounted. I wanted to make sure she was safe to ride. She proved to be ok but she was clearly still full of anxiety. However, the client had arrived and was waiting with Kathleen outside of the pen so that we could start her session. I decided this had to be good enough and we proceeded with the therapy session. We had the client mount and we started moving in a circle with me leading Gretta. At one point I remember the sun umbrella on the deck of the cabin suddenly falling over and spooking Gretta. She jumped sideways and almost lost our client but I was able to get her to stop. Gretta was obviously anxious and on edge the entire session – as we got to a certain section of the pen she would worry about something that was out in the trees. She would speed up and at times trot ahead of me as we passed this section of the pen. It was a stressful session for me as I had to do a lot of work trying to make sure Gretta was not going to hurt our client. I did not like having to manage all of that. I knew Gretta and I had a lot of work to do moving forward.

I made a lot of mistakes that first session and I took note of what I needed to improve and I started showing up at least an hour early for our sessions so that I could spend the appropriate amount of time connecting with Gretta and making sure I got true consent from her every step of the way before asking her to carry our client. I started really making sure Gretta was present when I made a request and that I was attuned to the emotions she felt around each request that I made. Typically, I would show up with the halter to bring her in and we would spend around 30 minutes in the paddock simply getting to the place in which she could look at me calmly, without anxiety, and then follow me at liberty while being fully present. I would offer the halter and wait for her to give me a clear yes and then proceed through the process of grooming and saddling and mounting with the same attuned concern for our relationship and her willful participation in the session. Her overall anxiety was starting to go down and things were improving steadily though she still seemed to be generally grumpy (and maybe even a little pissed) about being asked to do anything. It seemed to me that she typically felt lots of strong feelings in her daily life and just pushed them down and held them in – appeased, submitted, and dissociated. (Check out these two blogs to better understand dissociation with horses: When Dissociation Looks Like Cooperation or Six Signs Your Horse May be Dissociating or Submitting Rather than Choosing to Connect) When I would ask her to truly communicate with me how she felt about doing the things I was asking, it seemed I was the target of pent up aggression that she felt much of the time when I was not with her. Every morning an hour before session Gretta and I would work on this. It did not at all feel fair to me. I had no way of knowing if these outbursts towards me were a symptom of her daily life or a symptom of our relationship. What I did know, is that no matter what, I would have to be committed to doing the work to help her be less aggressive and more connected and I would have to do it slowly in that one hour before sessions on Tuesday mornings because that is all the time I could afford to spend with her. I would have to be happy taking improvements slowly as they came in hopes that the one hour I spent with Gretta each week, or every other week, would be enough to affect real change in her pattern of relating. Sound familiar? So I was committed to the relationship with Gretta and this is where we return to the morning that Kathleen arrives to discover me still asking Gretta to consent to the halter. (Can Animals Consent? – check out this blog on the subject)

It was a cold rainy day. The paddock had big sloppy hoof-shaped mud holes stomped out of it in the places where the horses preferred to gather around the round bale. It was not pleasurable to be out in the light mist trying to catch a horse for a therapy session that might not happen if it started raining any harder. So feeling some stress of my own I set out following Gretta through the mud and rain as she resisted basic engagement with me as usual. I stayed committed to our relationship – it seemed as though Gretta was begging me to take control of her – I refused.

At some point, Kathleen showed up and checked in on us. She watched for a bit and then had to return to the cabin to meet our client when she showed up. When the client arrived, she and Kathleen noticed me in virtually the same place with Gretta trying to resist and then comply but never really connecting with me. It started raining a little bit harder and Gretta was smart enough to move underneath the shed in the paddock. She would connect a little and follow me, then disconnect and resist and return to the shed where she would then reconnect with me. She seemed to be smart enough to want to continue this process out of the rain. I was happy to oblige. So. . . we were under the shed and were staying pretty connected and had progressed to working on accepting the halter. Gretta would get stark still and then try to check out (dissociate). I would ask her to reconnect and offer the halter and she would pull her head away showing tension in her ears and eyes and muzzle. I was acutely aware that our client had arrived and that I clearly did not have a horse prepared for mounted work. I expected Kathleen would have some other options and would arrive with the client to help her become a part of this process and that we would follow Gretta’s lead today. I was aware of my frustration and was consciously releasing the tension it caused in my body as I worked through this process with Gretta. Kathleen eventually emerged from the cabin asking if we were going to be ready soon. I was frustrated with this question as I thought it was pretty obvious that I could not give any definite answers to that question. Kathleen was polite but I could tell there was some tension and anxiety that accompanied the question. I suggested that she bring the client out so she could be a part of the process. Okay, so I basically suggested that Kathleen change the clinical plan for the session because the horse had not consented to participate.

It was not a comfortable feeling but I was not willing to accept compliance from Gretta, our client’s therapy partner. I was also keenly aware that I did not want to be responsible for the safety of a client on a horse who was anxious and had not consented to the halter and had certainly not consented to being ridden. The beauty of the situation is that both Kathleen and I were feeling some stress, pressure and anxiety, but were both able to regulate, relate, and reason so the session turned out to be beneficial for both horse and client. Remember, if it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either, and true healing cannot happen at the expense of another. This work is about connection and relationship – for the client AND horse.

In a perfect world, after that first session with Gretta, I would have set aside loads of time for us to work on lots and lots of stuff before she resumed mounted work in therapy sessions. We all did our best in the moment and tried to adapt and change and grow. We continue down that path.

Tanner and Kathleen are both NL trainers and will be teaching at the 2019 NL Conference. Check it out!

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Aug 5, 2019 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Case Studies, Parenting and Counseling Children, Personal Growth

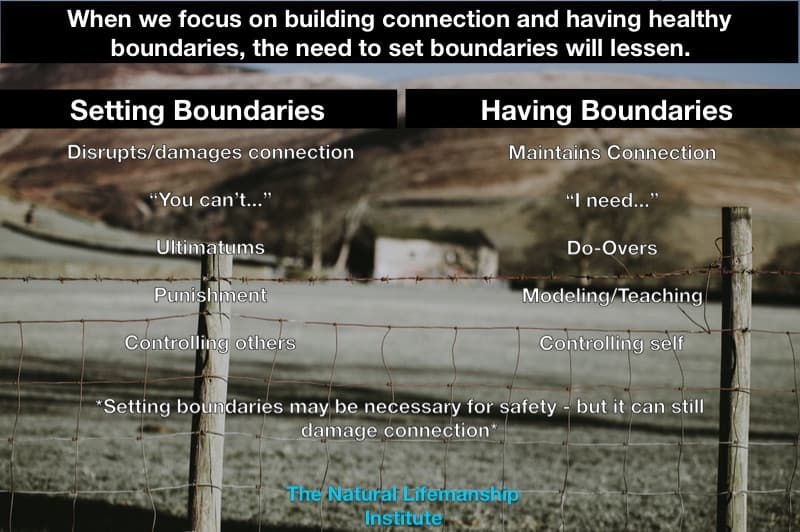

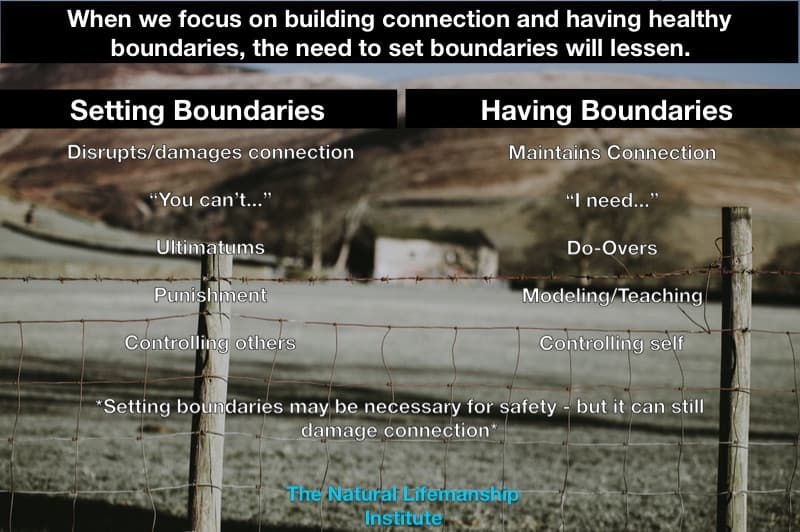

In this field, it is not uncommon to hear people answer the question “Why Horses?” with some variation of how horses help us learn how to set healthy boundaries. Is this true? Well, it depends. . .

In Natural Lifemanship we believe that horses help us learn how to build healthy, connected relationships. We teach that in order to build healthy connections we must have healthy boundaries. We also teach that the need to set boundaries is a connection issue – a connection issue that can only be addressed by seeking to build stronger connection.

Setting boundaries is certainly necessary at times to establish safety, but it is important to understand that while the setting of a boundary may establish safety it could also damage the connection. In a relationship that matters (one in which I plan to stay), it is our intent to build connection. Healthy boundaries are set by me for me, not for someone else by me. We also teach that in a healthy relationship it is important to focus on what I do want (connection), instead of focusing on what I don’t want. Typically, when a person is setting a boundary they are focused on what they don’t want, which often results in an attempt to control the other. AND when control enters the relationship, connection leaves – control of the other and connection simply cannot co-exist.

When doing TF-EAP or TI-EAL, it is important that when the subject of boundaries arises, we teach our clients how to build connection by having boundaries, rather than inadvertently teaching them to control others by setting boundaries.

Having boundaries simply put is:

- I am me and you are you.

- My body is my body, and I have a right to choose what happens with it

- My feelings are my feelings, and I have a right to my own feelings.

- My thoughts are my thoughts, and I have a right to my own thoughts

- It is not my job to fix others

- It is okay for others to feel any emotion – anger, sadness, rage, loneliness etc.

- I don’t have to read the minds of others or anticipate their needs

- It is okay to say no

- I need only take responsibility for myself

- Nobody has to agree with me

- This is a way of being in the world and in relationships

Timothy was a 9-year-old male participating in Trauma Focused Equine Assisted Psychotherapy (TF-EAP). He had a history of abuse and neglect. He struggled socially and was often bullied in school. He was in the foster care system. In 5 years he had lived in 12 different homes and gone to 10 different schools. When he started our program he chose to work with a mini horse named Ladybug who had some of the same struggles as Timothy. In fact, when asked why he chose Ladybug, Timothy said, “Because she is little and gets bullied a lot and has trouble making friends.” What he didn’t know is that Ladybug had quite a reputation, and as a result was not working in any other sessions. . . she was what horse people often call “mouthy,” and at times would straight up bite. Sweet little Ladybug could be quite intimidating to any person or animal she felt was smaller in spirit or stature – she was scared, so the survival regions of her brain tried to control others in an attempt to relieve her anxiety. All this resulted in her being bullied even more – she was covered in bite marks.

Timothy was intelligent, kind, had a great sense of humor, and . . . he was a hot mess! Gosh he was cute, but I didn’t have to live with him! His foster parents were simply beside themselves, and Ladybug understood why. Ladybug quickly picked up on his unpredictability and passivity, and within a couple sessions she was chasing Timothy while nipping at his rear. I have to admit, the horse person in me kinda wanted to tell him to pop her on the nose – SET a boundary! For Pete’s sake, she was bullying my client!

BUT we knew Timothy and Ladybug both desperately needed healthy connection to feel safe. Timothy needed to learn to have boundaries. If he had boundaries and healthy relationships, the need to set boundaries would lessen. He needed to learn to ask for what he needs, rather than focus on what he doesn’t want. Frankly, he had already tried telling his peers what not to do. He had told the teacher. He told his foster parents. The foster parents met with the school. The teacher told the other children to stop. And on and on. . . sigh. You all know the story.

So, Timothy began asking Ladybug for connection. At first, he had to ask her to move away because she was not safe, but he asked her to do this while still maintaining connection (more information about attachment and detachment in session). He didn’t tell her to go away. He would say, “Ladybug I want a friendship with you, but I need some space first. Can we be friends while you stand over there?” Then he would ask her to follow him while being present, calm, and kind. He danced back and forth between these two things for many weeks (as a side note: Timothy was meeting with us twice a week. He partnered with Ladybug one session and partnered with another horse for mounted work the other session). He practiced empathy – understanding how hard it was for Ladybug to connect instead of try to control, while still understanding that it is not his job to fix her. It was simply his job to make requests and then respond depending on Ladybug’s response. He was only responsible for his response to her. It was not his job to make her do anything or not do anything. There is a fine line between reflecting on what one could do differently and accepting responsibility for another’s aggressive behavior. Timothy practiced never accepting responsibility for her biting, while still realizing that he needed to practice assertiveness, focus, and connection. He had to give a little trust in order to get some trust – this took risk and vulnerability. He practiced allowing her to struggle without feeling the need to fix it – lots of deep breathes and time spent learning how to regulate.

No matter how Ladybug acted, Timothy would try to take a deep breath and say things like, “It is okay for you to be mad, but I still choose to be calm.” “I know this hard, but you can connect in a way that is safe for both of us.” He spent a lot of time learning what it means to ask Ladybug to be his friend, keeping the door open for that possibility, while maintaining the boundary that, “We can be friends when it is safe.” Timothy focused on his desire for connection, and kept in mind that Ladybug did want a friendship – she just wasn’t yet sure how to have one in a safe manner. He asked Ladybug to move away with connection and follow him with connection.

He did not learn to get big.

He did not make Ladybug go away as a punishment.

He did not yell.

He did not hit.

He focused on what he did want – a friendship – connection.

He learned to be assertive (use exactly the amount of energy needed to build a safe, connected relationship).

Ladybug completely quit biting and nipping at Timothy. The amazing thing is that Timothy never once asked or told Ladybug to stop biting! When she would nip at him, he would gently ask her to move away while still remaining calm and paying attention to him. He didn’t want her to withdraw because that damages connection. He didn’t want to scare her or punish her because that, too, damages connection. Then he would offer her a “do-over” (more information about Do-Overs). He would ask her to come back and see if they could experience connection through closeness in a safe way. Timothy learned to be soft, strong, calm, and comfortable in his own body. Over time he began to make friends and the bullying just seemed to stop. Ladybug’s relationship with her herd also seemed to change. We began to notice that the old bite marks had healed and there were no new ones.

I asked him one day why he didn’t think he was being bullied anymore and he said simply, “When you have good relationships you don’t get bullied.”

I asked him why he thought Ladybug was also no longer being bullied. He smiled at me, with so much pride in his face, and as he shrugged his shoulders he said, “When you have good relationships you don’t get bullied.”

by Jamie Morley | Apr 20, 2019 | Applied Principles, Case Studies, Testimonials & Reflections

In December 2017, I attended my first NL Intensive training in Brenham, TX. I’m pretty sure it was day two, which in my experience at these trainings, is when things really start getting stirred up internally. This life lesson came to me in my blind spot. Like a horse’s blind spot, it was right in front of my face (or maybe right behind my rear?). In fact, the only one who could see what was going on was my partner for the weekend.

I was in the round pen with the horse, Indigo (name has been changed for this article), trying to connect through attachment. When we had worked together the day before, we had a pretty quick connection, so I figured it would happen pretty easily again. This was not the case. Indigo was completely ignoring me. So I started to gradually increase my efforts, going from clucking and calling her name, to stomping my feet, to waving my hands in the air, to getting closer and jumping up and down and waving my hands all at the same time.

My partner stopped me (thank goodness!). I walked over to her and took a much needed break from all the jumping and flailing around. She said something simple like, “It seems to me like your energy on the outside does not match your energy on the inside”. At first I shot a quick answer back like, “Really? I feel like all of my energy is as high as it can go! I don’t know what else to do.” And then the thought settled somewhere deep within, and I took a deep breath and looked at her. She was right.

At some point, Tim Jobe had joined the conversation (he has a way of popping in at the just the right moment). He asked something to the effect of, “What might be keeping you from raising your internal energy?” I explained that it felt like there is a line that divides where I feel safe and comfortable to make an “ask” in a relationship and where it feels all together too risky and vulnerable. Tim asked, “What is the risk if you cross that line?” I started to process out loud about how if I gave more energy toward the relationship, what if it wasn’t reciprocated? What if she still kept ignoring me? The fear of losing what connection I did have seemed to outweigh the potential of gaining an even deeper connection. A wave of realization was rushing over me. This, of course, directly correlated to how I often felt in my human relationships.

Then something beautiful happened that I’ll never forget. By this point, I was back to standing in proximity to Indigo. As soon as I acknowledged my true inner feelings to Tim and my partner, Indigo turned and came toward me. She planted herself right there next to me as tears began to steadily stream down my face. I hadn’t even asked her to come over. She chose to all on her own. And all I could do was stand there next to her and let the tears fall freely. I savored that moment with her and all that she “said” to me through her actions.

In a way that only a horse can, she affirmed so many truths for me in this moment. She affirmed that all she wanted was the real me. She didn’t require that I had it all together. She only required that I was being real with myself and with her. It was as if she was saying, “Oh good, you’re truly present with me and now I want to come be with you”. She also affirmed that the experience of a connection like this was totally worth the risk and vulnerability it took to get it.

“Most people believe vulnerability is weakness. But really, vulnerability is courage. We must ask ourselves…are we willing to show up and be seen?”

–Brene Brown

Self-sufficiency has met her match, her name is Vulnerability. It’s only through vulnerability that true connection is experienced. Self-sufficiency may give a false sense of security, but it will forever leave me feeling disconnected from others. Indigo helped me realize that what I want more than independence and self-sufficiency is the sense of being known and accepted for who I am. In order to get this, I have to show up in relationships as my authentic, vulnerable, messy self.

Every day we have the choice. Today I choose vulnerability.

—————————————————————————

Jamie offers life coaching, both equine assisted and non-equine, to the Central Ohio area. She is dual certified through Natural Lifemanship as a Practitioner and an Equine Professional and is a certified Life Coach through the JRNI Catalyst Coaching Intensive. Her coaching business, Hope Anew, thrives on this motto: Healing Occurs through Purposeful Elements- Art, Nature, Environment, and Well-being. She loves taking creative approaches to helping people on their path to personal growth, as the path to transformation looks different for everyone!

by Kathleen Choe | Feb 16, 2018 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Case Studies, Testimonials & Reflections

How Cross Brain Connections Literally Saved My Life!

In this blog, I will discuss how a healthy brain develops and how trauma impacts this process by localizing neural connections in the lower regions of the brain, the part concerned with survival. I will share ways we can capitalize on the brain’s neuroplasticity and capacity to heal with strategies to increase cross brain connectivity, ending with an example of this from my own personal experience of being assaulted on two different occasions.

There is a great deal of discussion in Trauma-Informed Care about cross brain connections, neural pathways that connect throughout the different areas of the brain, leading to a greater capacity for self-regulation and smooth emotional state shifting in response to environmental cues. Brain development begins in utero, developing sequentially from the bottom to the top and from the inside out in response to sensory input. The first part of the brain to develop is the brainstem, which is responsible for regulating autonomic functions like heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, body temperature, sleep, and appetite. We generally do not have to think about these functions unless something goes wrong with them (during an asthma or heart attack, for example). The brainstem, which as its name suggests, is at the base of the brain, is responsible for basic survival and is where our fight, flight and freeze responses originate in response to a trauma trigger.

The next region of the brain to develop is the diencephalon, which regulates motor control. (When the freeze response is triggered by the brainstem it indicates that the diencephalon, as well as all of the regions of the brain above it, have essentially gone “offline”). Following that is the limbic system, which regulates our emotions and makes us capable of attachment and relational connection. The last part of the brain to develop is the neocortex, which allows for abstract and concrete thought, impulse control, planning and other aspects of executive functioning. The neocortex may not be fully developed and functional until well into a person’s second decade of life.

Trauma can be defined as input that is arrhythmic and unpredictable. If a pregnancy is unwanted, or the mother is in a chaotic environment due to poverty and domestic violence, or she struggles with a mental disorder or uses drugs, for example, the fetus is exposed to a barrage of arrhythmic sensory input in the womb. The mother’s heart-rate may be irregular, the cadence of her voice may be harsh or distressed, and her body may be secreting stress chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline that acid washes the womb for nine months. The part of the brain that receives the most sensory input will be the most well developed, as the neurons flock there in response to continuous activation. A baby experiencing intra-uterine trauma of any sort will be born prepared for survival, with most of his or her neurons clustered in the lower regions of the brain. A baby whose gestation was full of rhythmic, predictable sensory input from his mother’s well-regulated heartbeat, calm voice, and soothing chemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin, will be born with up to fifty percent of his neurons having migrated to the neocortex, ready for language and learning. Intra-uterine trauma primes the baby’s brain to form local connections in the lower regions of the brain in anticipation of being born into a chaotic, unpredictable environment. The foundation for future development is compromised, and any subsequent trauma layers on top of this shaky substrate to create a brain muscled up for survival and reactivity, with few cross brain connections allowing for a regulated, integrated response to environmental or relational stimuli.

Dr. Bruce Perry points out that trauma interferes with what he terms smooth “state shifting,” referring to the ability of the brain to communicate between all of its regions to come up with the best response to deal with the situation at hand. Healthy brain development allows a person to accurately interpret input and respond appropriately based on what is actually happening in the present. In the case of a car careening into your lane of traffic, the amygdala sounds the alarm in the limbic system, the diencephalon kicks in and prompts you to quickly maneuver out of the way, and the brainstem briefly shuts down unnecessary functions like digestion that would divert energy away from dealing with the crisis. The neocortex, which would unnecessarily delay the response time, essentially goes offline. Whether the car barreling towards you is a Mercedes or a Chevrolet is completely irrelevant to your survival. Determining the color, make or model of the vehicle occupies precious time and attention that keeps you in harm’s way longer than necessary and compromises your ability to keep yourself safe. When cross-brain connections are absent, and the different regions of the brain lack neural pathways to communicate efficiently, the array of responses a person has is limited. A traumatized individual might get stuck in his brainstem, lose access to his diencephalon, freeze, and be unable to turn the steering wheel, incurring a collision with the oncoming car.

This is essentially what happened to me when I was assaulted in my early 20’s in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. I was using a public restroom when a man who apparently had been hiding in the stall next to mine burst under the dividing wall and attacked me. I completely froze. I could not move, cry out, or think of how to defend myself. I never reported the assault or pursued any kind of help afterward. I simply left it buried in my brainstem and used my already active eating disorder and dissociative pathways to cope. When I unexpectedly became pregnant with my first child three years later, I realized my unhealthy patterns were going to affect my baby in damaging ways. Facing the huge responsibility of carrying and then caring for a child provided the incentive I needed to pursue healing in so many areas of my life. Although I worked hard on my recovery, my very stubborn pathways for dissociating from strong emotions and avoiding what I perceived to be the dangers of intimacy remained strong.

When I discovered Natural Lifemanship, I knew these principles of relational connection and partnership were the missing pieces to my healing puzzle. I was initially dismayed to find how much I struggled to experience connection in the round pen with the horses, but as I kept practicing asking for attachment and detachment, I found over time that I was starting to feel my emotions and body sensations more consistently and accurately, both with horses and with people. Through both ground (Relationship Logic) and mounted work (Rhythmic Riding), I strengthened the cross brain connections necessary to stay regulated and grounded without checking out in stressful situations. My sense of peace and confidence and ability to stay present and connected to myself continued to grow.

Last year all of this was put to the test when I was out running in my neighborhood early in the morning. I heard footsteps behind me on a narrow stretch of sidewalk bordered by tall hedges and a railing on either side and turned sideways, thinking another runner wanted to pass me. Instead, he grabbed me by the shoulders, muttered the word “sorry” and threw me to the ground. My brain immediately went into gear. Just the night before I had shared a public service announcement from the Austin Police Department with my running group concerning a sexual predator who had been assaulting female runners. I could literally see the list of suggestions in my mind and began sorting through them. “Make noise,” my brain said, and I started screaming as loud as I could. My assailant covered my mouth with his hand. “Fight back,” my brain commanded, and I shook one of my arms free and tried to push him off. As he tightened his grip, I remembered, “Strike where he is most vulnerable,” so I started reaching towards his groin area as best as I could. His eyes widened in surprise and he suddenly let go of me, slamming my head into the pavement. I don’t know how long I lost consciousness, but as I came to, I heard a voice shouting, “Get up! Get up! You have to get up NOW!” I realized the voice was my own; it was my brain, telling me I needed to mobilize in case he came back. I was able to get up and wobble up the hill until I met another runner who took me to her house and called 911.

I reported this assault. I went to the emergency room, made a statement to the police, and described the suspect to a forensic artist who captured his likeness quite accurately. I engaged in therapy, and spent hours in the round pen with horses, crying, connecting, and healing. I shared my experience with my running group and put together a tip sheet for runner safety, which I shared with other running groups in the area. I attended a self-defense class. Despite the temptation to revert to old patterns of dissociating from my fear and pain, I practiced feeling all the emotions in the aftermath of this trauma, letting myself weep when the detective called to say my suspect’s DNA was found on another victim. I gave myself permission to be scared, sad, and also proud. Proud that I had done the hard work to develop the cross brain connections that allowed me to fight back instead of freezing during my second assault. During my therapy for this attack, I was able to process my first one as well.

Cross brain connections are essential for flexible thinking and appropriate responses. Practicing mindfulness and grounding skills on a regular basis allows these neural pathways to develop and strengthen in a brain compromised by arrhythmic, unpredictable input. Research continues to highlight the neuroplasticity of the brain in response to rhythmic sensory input that allows it to heal and integrate following trauma. Expanding local connections into cross brain connections enhances our ability to experience emotional regulation so that we can build healthier, more satisfying relationships with ourselves and with others.

How does one build or repair cross brain connections?

A daily practice of mindfulness (meditation, yoga, or centering prayer, for example) has been shown to improve brain connection and functioning. Exposure to reparative or corrective relational experiences also contributes to building neural pathways from the lower to the upper regions of the brain. Trauma victims often repeat dysfunctional patterns in the relationship due to compromised neural connections in the brain, reinforcing their trauma pathways. Equine Assisted Psychotherapy involves partnering with a horse to provide opportunities for new pathways to form a healthy relationship is built between horse and human under the guidance of a therapist and equine specialist. Clients learn how to build and sustain healthier relationship patterns as their brains literally re-wire through the experiential component of the therapeutic work with the horses. Through a combination of ground and mounted work, a person can learn self-regulation skills, positive coping resources, and begin to heal from their trauma.

What are cross brain connections good for? At some point, they just might save your life.

For more information, check out the following website: naturallifemanship.com

*Dr. Daniel Siegel’s Wheel of Awareness is an excellent resource for developing such a practice, as is St. Michael’s Hospital Awareness Stabilization Training.

by Greer Swiatek | Jan 10, 2018 | Case Studies

Case Study About a Boy Seeking Connection

Oliver was sitting in a stall with Banjo, holding a saddle close to his chest, slumped over in defeat. It was yet another session that he tried to ride Banjo and failed. The Equine Professional and I stayed connected with Oliver, guiding him through self-regulation exercises and resisting the urge to rescue him or provide detailed instructions. Oliver wanted us to provide direction and he became frustrated at times when we encouraged him to find his own path to connecting with Banjo. Banjo stood beside him, patiently waiting and breathing slowly. Oliver continued to hug the saddle and his eyes seemed to glaze over at times like he was a thousand miles away. Banjo stomped one hoof, then another. Oliver blinked a few times and looked at him. Oliver started to check out again, but not for long. Banjo continued to make the request for him to stay present, using body movement and breath to get Oliver’s attention. Banjo was consistent and they continued this back and forth interaction until Oliver became calm and fully present. Oliver tilted his head and stared at Banjo with a gleam in his eye, a slow smile appeared on his face. It was in that moment, while sitting in the corner of the stall, that hot summer day, that something shifted in Oliver. He dropped the saddle, took a big belly breath and realized that this relationship was going to be different…it had to be different.

Oliver’s chronic anxiety led to an environment where his family managed almost every aspect of his life. He had little independence. At 12 years old, he was sleeping in his parent’s bed with the overhead light left on. Oliver was afraid of the dark, among other things. With peers, he tended to be controlling and confrontational; he struggled with reciprocity in play. During our intake session, Oliver hid behind his mother, continuously rolling his eyes, speaking in a goofy voice, and laughing nervously after everything he said. He avoided eye contact and deflected direct interaction. His parents answered questions for him. When we redirected our attention to Oliver, he appeared startled and confused, like he had just woken up.

After picking Banjo that first day, Oliver walked, almost stomped, directly to the barn. We had to jog a bit just to keep up with him. He told us he wanted to ride Banjo and looked at us expectantly. The Equine Professional and I paused and looked at each other to check in, communicating non-verbally that we were on the same page. We knew that if we intervened and said “no”, we would be setting the tone for the therapeutic relationship going forward, one of power and control. Instead, we trusted the process, we trusted ourselves, and we relied on Natural Lifemanship Principles. We communicated to Oliver that only he could decide what was best for his relationship with Banjo. Over the next several sessions, Oliver and Banjo danced. Oliver moved forward with the saddle and Banjo moved away. At times Oliver was able to self-regulate, opening himself up for connection. In these moments, Banjo moved closer to him. Oliver got excited, quickly grabbed the saddle and marched over to meet Banjo. Banjo immediately backed away. Eventually, Oliver realized that his agenda to ride was taking him further away from what he desired most, connection.

Oliver then chose to move from the barn to the round pen to work on his connection with Banjo. He often began sessions by pacing around the perimeter of the round pen, pulling weeds and throwing them out of the round pen like a baseball. At first, this startled Banjo, but Banjo continued to be patient and cautious. Picking and throwing weeds was a regulating activity for Oliver that allowed him to connect with himself. His connection with-in opened the door for connection with Banjo…Banjo began to follow Oliver, stopping when he stopped to pick up another weed and launch it outside the round pen. Oliver would then continue to walk and Banjo would follow. At times, Oliver would run around the round pen and request Banjo to follow him. Banjo is an older horse and preferred to walk. Oliver was able to stay connected and realize that Banjo had some requests of his own. Their connection grew stronger. At times, Oliver’s mind would wander while he walked, Banjo would gently nudge him in the shoulder to help him stay present. Oliver found his own way to regulate and connect, by pulling and throwing weeds. This was more powerful than anything we could have suggested because it came from within. It was a reminder to keep the process client-led and provide a space for our clients to experiment and explore.

One day, Oliver came to session after a particularly hard day at school. He was having trouble regulating himself and asked for our help as he sat in the middle of the round pen. I asked Oliver to lie down on the ground and close his eyes while the Equine Professional put Banjo on a lead rope. Oliver became attuned to his breath and the ground beneath him, engaging the lower regions of his brain. We then asked him to bring his awareness to Banjo, bringing his limbic system online. The Equine Professional walked with Banjo around the pen while Oliver kept his eyes closed and tapped into his other senses to locate Banjo. Oliver was engaging in bottom-up regulation. He then used his neocortex to problem solve where Banjo was in the round pen while continuing to regulate the lower regions of his brain by rhythmically rocking back and forth. While his eyes were still closed, Oliver made a request for connection. He wanted Banjo to stop eating grass and to come to greet him in the center of the pen. The Equine Professional dropped the lead rope. We asked Oliver to imagine what it would look and feel like for Banjo to approach him while keeping his eyes closed. “Well, he would take one step forward….then he would eat a little more grass…then take another step forward…then another step” Oliver replied.

Banjo began to slowly approach Oliver, one step at a time while continuing to enjoy the delicious grass beneath him. Oliver became a little impatient. He took a big belly breath and said, “I wish he would just hurry up”. Banjo immediately pulled his head up from grazing and quickly walked over to Oliver, nuzzling his hair when he reached him. Oliver opened his eyes and laughed in pure joy.

Oliver was building pathways in his brain for a new way of interacting with others and began to employ a whole-brain understanding that true connection comes from within.

by Kathleen Choe | Aug 22, 2017 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Case Studies

In his latest book, The Divine Dance, author Richard Rohr quotes a psychiatrist friend of his as attributing most non-physiologically based mental illness to being disconnected from intimate relationships. While he acknowledges biological and genetic underpinnings to the development of a mental disorder, in his view, “loneliness is what activates it.”

Maia Szalavitz echoes this idea in her book on addiction titled Unbroken Brain where she points out that addicts in treatment programs that emphasize supportive, empathetic relationships where they are treated with respect and dignity have higher recovery rates than those in “tough love” programs based on more shame-based, punitive principles.

We have a natural need for bonding and connection

In his exploration of what causes some people to become addicts when exposed to drugs and other to remain recreational users, Johann Hari notes in his Ted Talk: “Human beings have a natural and innate need to bond, and when we’re happy and healthy, we’ll bond and connect with each other, but if you can’t do that, because you’re traumatized or isolated or beaten down by life, you will bond with something that will give you some sense of relief. Now, that might be gambling. That might be pornography. That might be cocaine. That might be cannabis, but you will bond and connect with something because that’s our nature. That’s what we want as human beings.”

Research consistently shows that people with strong ties to family, friends and community live longer and have better psychological, emotional and physical health than those who are isolated. They also report less depression and anxiety, a more positive self view and a greater sense of satisfaction with their life overall. Loneliness is not only a difficult experience emotionally, but often results in our making choices that negatively affect our psychological and physical health as well. We may turn to addictions like alcohol, drugs, pornography, and gambling to fill the emptiness we feel inside. Environmental stressors may pull the trigger on a pathway we are genetically pre-disposed to, like an eating disorder, that gives us the illusion of control and self-protection from rejection or other relational wounds.

Attachment and coping measures

Based on our early attachment experiences in childhood, when we are upset or frightened we either move towards or away from relationships for comfort. If our needs were consistently met in nurturing ways by attuned caregivers in infancy, we view the world as a generally trustworthy place and expect to find support when we seek solace from others. If we experienced neglect, abuse, or mis-attuned responses such as being ignored when upset or stimulated when fatigued and in need of rest, we learn that relationships are not a source of safety but of confusion or harm. Our needs may be invalidated or negated in ways that leave us unsure of the accuracy or importance of our own feelings, wants and perceptions. We become filled with shame, self doubt, and insecurity and seek ways to soothe and regulate our emotional distress since co-regulation with caregivers is not a reliable option.

Children have limited resources to turn to for coping measures. Often food is one of the options available and rather than our eating being regulated by hunger and fullness, we start using food to change our emotional states. Restricting can lead to a sense of euphoria and power. Bingeing can lull our senses into a state of numbness and help us detach from painful feelings of shame or fear. Instead of responding to physical cues of appetite and satiety, we eat (or don’t) in response to emotional cues. Again, moving towards safe relationships can be a powerful interruption to these established emotional eating habits.

Having a positive relational exchange releases oxytocin, known as “the cuddle hormone.” Oxytocin has been shown to regulate appetite, decrease hunger and increase positive feelings of well being. This release has even been documented in humans who spend time with animals. Petting a dog or cat can lower heart rate and blood pressure and release chemicals in the blood stream like oxytocin that decrease our craving for food and interrupt the emotional eating pathway.

Likewise, reaching out to a friend for support instead of reaching for that bag of chips or carton of ice cream can fill the void in a way that food never will. This involves risk. Food does not reject, criticize or ignore us. It is generally available and delivers consistent taste, texture, and “results” in terms of the sedating or numbing effect we are seeking in that painful moment. A friend may not respond, or respond in a way that feels unhelpful, which only adds to our distress.

Investing in healthy relationships

Building a strong network of supportive, caring relationships requires an investment of time and energy and a willingness to experience relational wounds and repairs on an ongoing basis. Having this network, however, will increase the chances of a positive response to our bid for support and decrease our dependence on ultimately self-destructive and unsatisfying coping methods that only temporarily distract from our pain, rather than becoming a source of healing and recovery.

Healthy relationships are an important part of building resilience to life’s stressors as well as for recovery from addictions, disorders and trauma. People who have developed an insecure attachment style due to early childhood abuse or neglect, or whose ability to trust has been damaged by trauma, may have difficulty building the positive types of relationships that promote healing and recovery.

The Natural Lifemanship model of Equine Assisted Psychotherapy focuses on helping people develop secure, attuned relationships. Experiencing a strong therapeutic alliance with a qualified therapist can help someone learn how to have secure attachments and create connected, attuned relationships outside of the therapy office. Equine assisted therapy focuses on building this connection with a horse and then transferring the principles to human relationships with greater confidence of success.

If you feel isolated or stuck in unhealthy relationship patterns, go to naturallifemanship.com to find a qualified therapist who can help.

If you work with clients around addiction, check out our Disease of Disconnection course, a trauma-informed understanding of addiction to reveal the underlying factors that create and perpetuate the addiction cycle.

Recent Comments