by Sara Sherman | Mar 6, 2020 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Equine Assisted Trainings, Testimonials & Reflections

Sara Sherman is the founder of and a coach at Discovery Horse

Our business, Discovery Horse, has been doing a large volume of work in our community in MN. As our circle of influence grew it became essential that I have a succinct definition of Relationship Logic (the ground component of Natural Lifemanship) that I could share in our conversations with the community. I grabbed some language from the NL website and wrote a few words of my own. The following is the result of that endeavor. I hope it can be as helpful to you and your communities as it has been to mine. There are 2 versions. The first is a little wordier and clinical. I use this one for conversations with other mental health professionals and their agencies. The 2nd version is shorter and more easily digestible.

More in-depth version:

Relationship Logic® (RL) was developed by Natural Lifemanship and offers us a way to bring sound, consistent principles to the relationships in our lives. RL teaches that building attuned, connected relationships is always the primary goal from which other desirable outcomes follow. RL offers the neuroscience that empowers us to identify relationship patterns while maintaining the belief that our brains can change through new and healthy experiences. The ability to identify those patterns in a way that informs both compassionate understanding and a clear path to healthy change is an essential step toward healing, growth, and transformation. The principles we teach are the principles we practice and model in all of our relationships. We allow simple relationship principles to guide us as we work to transform these patterns. Behavioral patterns, especially those acquired in the early stages of development, are largely subconscious. They exist in the body and manifest as automatic reactions to situations we encounter each day. They become habitual. The way to change old patterns that no longer serve us is to practice something new. RL principles may be practiced in relationships with other people, and even within our relationships with ourselves, our families, animals, and communities. As these are practiced both during sessions and in daily life, new healthy patterns for relationships begin to replace old patterns that no longer serve us well. Connected and attuned relationships lead to healthy development; they contribute to healing at any age and enhance well-being.

Shorter Version:

Relationship Logic® (RL) was developed by Natural Lifemanship and offers us a way to bring sound, consistent principles to the relationships in our lives. RL teaches that building attuned, connected relationships is always the primary goal from which other desirable outcomes follow. RL offers the neuroscience that empowers us to identify relationship patterns while maintaining the belief that our brains can change through new and healthy experiences. The ability to identify these patterns in a way that informs both compassionate understanding and a clear path to healthy change is an essential step toward healing, growth, and transformation. The principles we teach are the principles we practice and model in all of our relationships. The way to change old patterns that no longer serve us is to practice something new. RL principles may be practiced in relationships everywhere; with ourselves, our families, our work teams, animals and communities. Connected and attuned relationships lead to healthy development; they contribute to healing at any age and enhance well-being.

Get started on your path with the Natural Lifemanship Institute.

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Aug 5, 2019 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Case Studies, Parenting and Counseling Children, Personal Growth

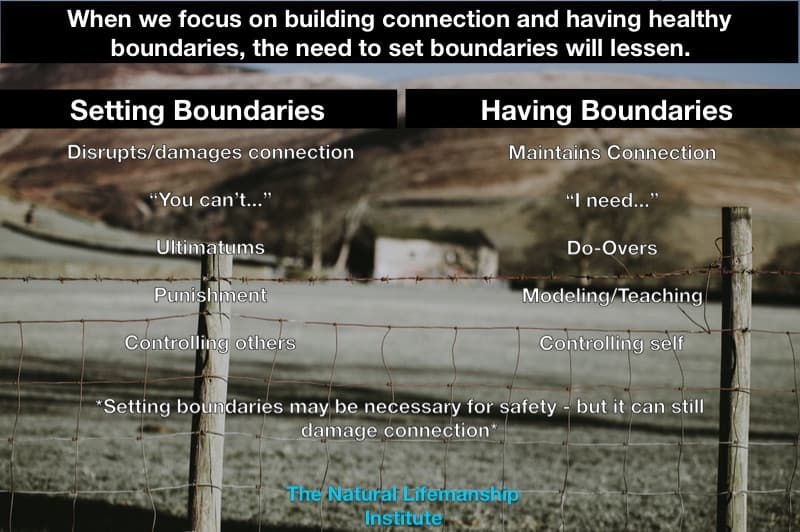

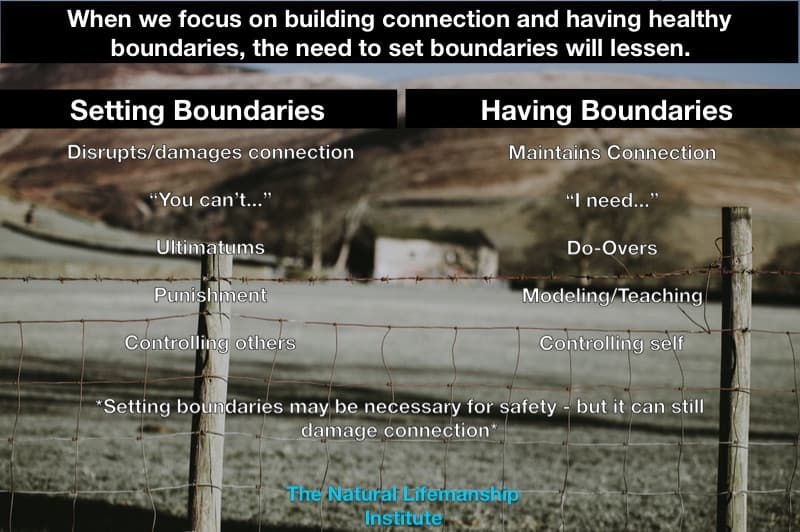

In this field, it is not uncommon to hear people answer the question “Why Horses?” with some variation of how horses help us learn how to set healthy boundaries. Is this true? Well, it depends. . .

In Natural Lifemanship we believe that horses help us learn how to build healthy, connected relationships. We teach that in order to build healthy connections we must have healthy boundaries. We also teach that the need to set boundaries is a connection issue – a connection issue that can only be addressed by seeking to build stronger connection.

Setting boundaries is certainly necessary at times to establish safety, but it is important to understand that while the setting of a boundary may establish safety it could also damage the connection. In a relationship that matters (one in which I plan to stay), it is our intent to build connection. Healthy boundaries are set by me for me, not for someone else by me. We also teach that in a healthy relationship it is important to focus on what I do want (connection), instead of focusing on what I don’t want. Typically, when a person is setting a boundary they are focused on what they don’t want, which often results in an attempt to control the other. AND when control enters the relationship, connection leaves – control of the other and connection simply cannot co-exist.

When doing TF-EAP or TI-EAL, it is important that when the subject of boundaries arises, we teach our clients how to build connection by having boundaries, rather than inadvertently teaching them to control others by setting boundaries.

Having boundaries simply put is:

- I am me and you are you.

- My body is my body, and I have a right to choose what happens with it

- My feelings are my feelings, and I have a right to my own feelings.

- My thoughts are my thoughts, and I have a right to my own thoughts

- It is not my job to fix others

- It is okay for others to feel any emotion – anger, sadness, rage, loneliness etc.

- I don’t have to read the minds of others or anticipate their needs

- It is okay to say no

- I need only take responsibility for myself

- Nobody has to agree with me

- This is a way of being in the world and in relationships

Timothy was a 9-year-old male participating in Trauma Focused Equine Assisted Psychotherapy (TF-EAP). He had a history of abuse and neglect. He struggled socially and was often bullied in school. He was in the foster care system. In 5 years he had lived in 12 different homes and gone to 10 different schools. When he started our program he chose to work with a mini horse named Ladybug who had some of the same struggles as Timothy. In fact, when asked why he chose Ladybug, Timothy said, “Because she is little and gets bullied a lot and has trouble making friends.” What he didn’t know is that Ladybug had quite a reputation, and as a result was not working in any other sessions. . . she was what horse people often call “mouthy,” and at times would straight up bite. Sweet little Ladybug could be quite intimidating to any person or animal she felt was smaller in spirit or stature – she was scared, so the survival regions of her brain tried to control others in an attempt to relieve her anxiety. All this resulted in her being bullied even more – she was covered in bite marks.

Timothy was intelligent, kind, had a great sense of humor, and . . . he was a hot mess! Gosh he was cute, but I didn’t have to live with him! His foster parents were simply beside themselves, and Ladybug understood why. Ladybug quickly picked up on his unpredictability and passivity, and within a couple sessions she was chasing Timothy while nipping at his rear. I have to admit, the horse person in me kinda wanted to tell him to pop her on the nose – SET a boundary! For Pete’s sake, she was bullying my client!

BUT we knew Timothy and Ladybug both desperately needed healthy connection to feel safe. Timothy needed to learn to have boundaries. If he had boundaries and healthy relationships, the need to set boundaries would lessen. He needed to learn to ask for what he needs, rather than focus on what he doesn’t want. Frankly, he had already tried telling his peers what not to do. He had told the teacher. He told his foster parents. The foster parents met with the school. The teacher told the other children to stop. And on and on. . . sigh. You all know the story.

So, Timothy began asking Ladybug for connection. At first, he had to ask her to move away because she was not safe, but he asked her to do this while still maintaining connection (more information about attachment and detachment in session). He didn’t tell her to go away. He would say, “Ladybug I want a friendship with you, but I need some space first. Can we be friends while you stand over there?” Then he would ask her to follow him while being present, calm, and kind. He danced back and forth between these two things for many weeks (as a side note: Timothy was meeting with us twice a week. He partnered with Ladybug one session and partnered with another horse for mounted work the other session). He practiced empathy – understanding how hard it was for Ladybug to connect instead of try to control, while still understanding that it is not his job to fix her. It was simply his job to make requests and then respond depending on Ladybug’s response. He was only responsible for his response to her. It was not his job to make her do anything or not do anything. There is a fine line between reflecting on what one could do differently and accepting responsibility for another’s aggressive behavior. Timothy practiced never accepting responsibility for her biting, while still realizing that he needed to practice assertiveness, focus, and connection. He had to give a little trust in order to get some trust – this took risk and vulnerability. He practiced allowing her to struggle without feeling the need to fix it – lots of deep breathes and time spent learning how to regulate.

No matter how Ladybug acted, Timothy would try to take a deep breath and say things like, “It is okay for you to be mad, but I still choose to be calm.” “I know this hard, but you can connect in a way that is safe for both of us.” He spent a lot of time learning what it means to ask Ladybug to be his friend, keeping the door open for that possibility, while maintaining the boundary that, “We can be friends when it is safe.” Timothy focused on his desire for connection, and kept in mind that Ladybug did want a friendship – she just wasn’t yet sure how to have one in a safe manner. He asked Ladybug to move away with connection and follow him with connection.

He did not learn to get big.

He did not make Ladybug go away as a punishment.

He did not yell.

He did not hit.

He focused on what he did want – a friendship – connection.

He learned to be assertive (use exactly the amount of energy needed to build a safe, connected relationship).

Ladybug completely quit biting and nipping at Timothy. The amazing thing is that Timothy never once asked or told Ladybug to stop biting! When she would nip at him, he would gently ask her to move away while still remaining calm and paying attention to him. He didn’t want her to withdraw because that damages connection. He didn’t want to scare her or punish her because that, too, damages connection. Then he would offer her a “do-over” (more information about Do-Overs). He would ask her to come back and see if they could experience connection through closeness in a safe way. Timothy learned to be soft, strong, calm, and comfortable in his own body. Over time he began to make friends and the bullying just seemed to stop. Ladybug’s relationship with her herd also seemed to change. We began to notice that the old bite marks had healed and there were no new ones.

I asked him one day why he didn’t think he was being bullied anymore and he said simply, “When you have good relationships you don’t get bullied.”

I asked him why he thought Ladybug was also no longer being bullied. He smiled at me, with so much pride in his face, and as he shrugged his shoulders he said, “When you have good relationships you don’t get bullied.”

by Sarah Willeman | Aug 20, 2018 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Equine Assisted Trainings, Testimonials & Reflections

By Sarah Willeman

Building Connected Relationships

Horse-assisted psychotherapies show tremendous promise in helping people with trauma, which is notoriously difficult to treat. Trauma lives not only in our conscious mind but deeper in our nervous system, in parts of the brain responsible for basic survival. We can’t will our way—or talk our way—out of it. Horses can help people regulate those deeper brain regions. Recently I attended a training in one particular therapy model that’s captured my attention. It’s based on healing through connected relationships, beginning with the horse.

The Model

The model is called Natural Lifemanship. I found the name corny at first, but now I get it. Beyond just therapy, this is a way of being in the world—a guiding mindset for building relationships in all areas, with people and animals. The Natural Lifemanship school of therapy is called Trauma-Focused Equine-Assisted Psychotherapy (TF-EAP). It’s based on the structure and function of the brain, and it combines neurobiology with sound relationship principles. People learn these principles in the context of their relationship with the horse and can then transfer them to other relationships in their lives.

The founders, Bettina Shultz-Jobe and Tim Jobe, have backgrounds in psychotherapy with at-risk groups and horsemanship with challenging cases, like wild mustangs. (In his job starting mustangs, Tim could take a horse never before touched by a person and be riding him in a couple of hours—and not through coercive techniques.) In other words, the founders have deep expertise with both horses and psychology. And the method goes far beyond just that “magical” quality that contact with horses can have. This work has clear principles, organization, and purpose and has helped a lot of people.

The Neurobiology

A horse’s brain works in similar ways to that of a traumatized person: the lower, survival-focused brain regions are largely running the show.

The Equine Brain

Horses’ brains are naturally built this way. Compared to humans, horses have a small neocortex, the region responsible for thinking. In herd life, only the lead mare needs to do much thinking. Horses mainly need their fight-or-flight reflexes, and they need to follow the herd. Survival is the horse’s essential skill, and it’s governed by the lower brain.

The Human Brain in Trauma

With trauma, a person becomes stuck in those same lower brain regions. The fight-or-flight response actually has a third component: it’s fight, flight, or freeze. When a person is stuck in these states, the survival regions of the brain get over-exercised, the nervous system becomes dysregulated, and the person has trouble regaining internal calm—the calm that’s necessary for good relationships and physical wellbeing.

That over-exercising of the lower brain leads to two things, anatomically: it builds up the lower brain and simultaneously sacrifices connections to the upper brain regions, where thinking and emotional connection happen. There’s a use-it-or-lose-it phenomenon with brain pathways. A traumatized person has trouble with self-regulation because many of the cross-brain connections that allow us to consciously calm our survival reflexes have been lost—or in the case of childhood trauma, perhaps never created.

Healing the Brain

The good news is the brain has plasticity, and new connections can be formed. The most effective trauma therapy will first regulate the lower brain and then engage the upper brain regions, thereby forming new pathways, helping all parts of the brain to integrate with each other for healthy functioning.

In Natural Lifemanship, it’s crucial to understand which part of the brain a horse or person is responding or reacting from. (Responding is associated with calm, integrated thinking; reacting is habitual and reflexive.) This understanding is important because if someone’s in survival mode and you try to reason with their thinking brain, they’re simply not there to receive what you have to say.

Horses demonstrate this phenomenon. A scared horse cannot learn. The best horsemen understand that training through intimidation will ultimately fail. The horse might robotically comply out of fear, but he’ll eventually make a panicked mistake, or try to run away from the rider’s signals, or become injured from the constant stress. But a horse in a calm, connected state can develop and flourish.

And here’s what gives rise to a powerful road to healing: humans and horses are born with an innate desire to connect.

We want to form safe, caring bonds with other beings; we yearn for experiences of trust and mutual understanding. In fact, as psychology’s well-established field of Attachment Theory teaches, we need those safe connections in order to have a healthy nervous system. Natural Lifemanship uses the power of emotional connection to heal and integrate the brain of both human and horse.

How Natural Lifemanship Works

Although the principles can be applied in any setting, the primary mode of TF-EAP is working with horses in the round pen.

The person gradually builds a healthy, connected relationship with the horse by learning to make requests of the horse, recognize the horse’s signals, and respond appropriately.

This process requires the person to become aware of her internal state, which the horse instinctually senses. (You could do the same outward gestures with different internal states and get a completely different reaction from the horse.) Throughout the work, the therapist and horse together help the person develop self-awareness and self-regulation, as new neural pathways are formed.

If the person’s nervous system is too agitated, the therapist can use specific techniques to calm those lower brain regions. Certain types of sensory input and movement—namely, rhythmic and repetitive—have been found to regulate and soothe the nervous system. (Think of a steady heartbeat or rocking a baby.) TF-EAP therapists use a variety of proven methods to help the client regulate her brain from the bottom up; in other words, beginning with the lowest brain region that needs support. The survival-focused brainstem has to settle before higher brain regions like the limbic system and neocortex can be engaged in relationship-building activities.

The Horse-Human Relationship

A connected relationship is one in which both parties choose to do what’s right for the relationship, and those choices are made freely and willingly.

In Natural Lifemanship, the relationship with the horse is not a metaphor or proxy for a human relationship; rather, it’s a real relationship. Although there’s apparent overlap with many schools of Natural Horsemanship, there are important differences, too. Instead of viewing the human as the horse’s leader and asking the horse to be submissive, Natural Lifemanship seeks a dynamic of mutual respect and trust, with self-regulation and good decision-making on both sides. The horse learns to pause, think and freely choose to do the right thing.

This key conceptual difference arises from the model’s basis in neurobiology. Just as a human can develop new neural pathways, a horse can, too. Interactions with humans offer a unique opportunity to actually build up the horse’s neocortex (and capacity for self-regulation) in a way that wouldn’t happen in herd life.

And because horses are so direct—their responses are immediate and honest—they provide excellent feedback for the person. Horses sense how we really feel. Communication is visceral and genuine. When it goes well, there is a simple, genuine pleasure. Connection is inherently rewarding for both human and horse.

As human and horse begin to co-regulate, they help each others’ nervous systems become calm, integrated and functional. And that quality of mutual benefit is essential for true connection and healing. Natural Lifemanship teaches a profoundly empowering skill: how to develop a strong relationship that’s good for both parties.

These are two key principles:

- “If it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either.”

- “Regardless of the task or activity, connection is always the goal.”

These principles can be applied to work with horses and to all relationships with people and animals.

Compliance Versus Cooperation

In order to create connection, we need to understand the difference between compliance and cooperation. Compliance is a submissive action; it’s reflexive and robotic, arising from the lower brain’s survival instinct. On the other hand, cooperation is willing and freely chosen, arising from an integrated, whole-brain process in which the horse calmly figures out what to do.

So how do we tell the difference?

Well, it can be hard, because both can lead temporarily to very similar outward behaviors. Certainly, there are emotional cues, which can be subtle. But the real answer lies in the process.

Asking For Connection

As Natural Lifemanship explains, “Connection is predicated on a request.” In other words, rather than waiting for connection to magically happen, we need to ask for it. And how we ask—or how strongly we ask—has a major impact on the horse’s (or person’s) response.

The teaching is this: neither placate nor coerce. Both those extremes will eventually lead to aggressive behavior from the horse. (And as we talk about the horse here, continue to think of parallels with people.) Between those extremes lies the powerful zone of growth and connection.

An essential part of the process in TF-EAP is learning to make requests in an authoritative, calm manner, using the appropriate amount of pressure.

The Pressure Continuum

In this context, pressure is not a bad thing but just a fact of the universe. Making a request is a form of pressure. The goal is to use the least amount of pressure necessary.

Too little pressure and we’ll get ignored. Too much pressure and we’ll get fight-or-flight-type reactivity. Imagine an example: if someone yells at you when you’d’ve been happy to listen to a kind request, you might be mad (fight) or scared (flight) or too startled to know what to do (freeze).

Similarly, too much pressure can scare or anger a horse. If he’s in this state and still complies with our immediate request, he’s in his survival brain. This is not freely-chosen cooperation, and it’s not connection.

The appropriate amount of pressure compels the horse to search for an answer but leaves his options open, so he can figure it out and make a voluntary choice. This is the sweet spot of learning and relationship-building.

When we make a request of the horse, he can do one of three things: ignore, resist or cooperate. Herein lies one of the most powerful insights of the work: resistance is not necessarily bad. It means he’s trying to find an answer.

If he tries some wrong answers, we just keep the pressure the same. In order to do so, we need to stay calm and maintain control of our body energy, which can be hard to do when we’re not getting what we want. (Master horsewoman Sarah Dawson described this phenomenon during foal training: “I have to be careful I don’t take offense to any of the wrong answers he tries. He’s just trying to figure it out.”) We need self-awareness and self-regulation in order to succeed at this step.

Then—and this is equally crucial—when the horse begins to find the right answer, we immediately release the pressure. Which probably sounds familiar; the timing of pressure and release is the most fundamental skill of horse training. But you’d be surprised how often people mess this up, with horses and with other humans.

In the Round Pen

So, what does all this look like in the round pen?

With the horse lose in the pen, we apply pressure by raising the energy of our body and directing that energy—movement, sound, internal state—toward the horse.

We might lift our arm or swing a rope; cluck or make other sounds; walk more energetically or, at the extreme end, stomp our feet. Depending on the sensitivity of the horse, we could get a response from just a small shift in our energy. The specific direction of our energy is crucial, beginning with the direction of our gaze.

And an important note: we need to learn to raise our energy while maintaining a state of calm. Energy and agitation are not the same thing.

In the following series of photos, I’m working with Cruz on attachment, which is a central part of the method. In this case, attachment means I’m asking him to follow me. Here’s what to look for:

The Request

To ask Cruz for attachment, I apply pressure to his hindquarters. (Another difference from typical horse training, which drives the horse forward from the hindquarters. Here, to ask him to move forward I’d apply pressure near the girth region, where my leg would be if I were riding.) To begin with the least amount of pressure, I simply look at his hindquarters, with my torso pointing toward that part of his body. If necessary, I can increase my body energy and movement from there.

The Release

I want him to turn his attention toward me and begin to move in my direction, so those are the things I reward by releasing pressure—specifically, by lowering my body energy/movement/gestures, backing away, softening my voice, or actually turning and walking away. I don’t reward submissive gestures like dropping his head and licking his lips. If he does those things after I’ve released the pressure, that’s all right; it’s a sign of relaxation (along with yawning, sighing or snorting in that particular relaxed horsey way). But if he does those things in response to pressure, it’s a reflexive, lower-brain attempt at submission, which we don’t want.

The Connection

When he attaches and follows me, I let myself really feel the enjoyment of it—which he senses and enjoys as well.

So let’s begin…

Cruz ignores the subtler signals, so I kiss to him and swing the rope to help me raise my body energy:

He searches for an answer by trotting away, but since that’s not what I’m asking, I keep the pressure the same:

As soon as he starts to slow down and shift his attention toward me, I lower the rope and back away. He walks toward me; I release further by turning and walking away, allowing this sense of connection to soothe my own nervous system:

When he reaches me, I stand with him calmly, letting my body energy completely relax. I scratch his withers, praise him, and enjoy hanging out with him:

Then I ask him to follow me again, simply by looking toward his hindquarters and kissing to him. This time, he responds to those cues—much less pressure than before—and attaches:

When his attention wanders, I simply notice and make the request again, using the least amount of pressure necessary:

Again, he attaches, and we both enjoy the connection:

We finish by standing quietly together again. Even when he looks across the round pen, we’re still connected. He’s relaxed, not alarmed by whatever he sees, and he easily brings his attention back to me (notice the tilt of his ear in the second photo):

Photo series by my husband, Philip Richter

Horsemanship Insights

The legendary horseman Bill Steinkraus wrote, “Since the horse will have the last word in any case, we must try to ensure, through skill, tact, and moderation, that this last word is ‘yes.’”

Natural Lifemanship explains what that “skill, tact and moderation” consists of in its most evolved form: it’s about understanding the horse’s mind, including the neurobiology, in order to form a true partnership.

The very best compassionate horsemen might talk about leadership and submission (both Steinkraus and Sarah Dawson sometimes do, eg.) But in practice, the way they relate to their horses aligns closely with Natural Lifemanship principles. The best horsemen do create partnerships of mutual respect and trust. For them, this framework can provide some new language, a subtle shift in thinking, and a brain-based explanation for why their methods work. Plus maybe a few new tools and techniques, in the round pen and elsewhere.

In other cases, horse trainers could benefit from a major paradigm shift that encompasses not only their ideas but also their actions.

The Main Ideas

Submission should not be the goal. We do need to stop the horse from misbehaving because it’s not good for the relationship. But we don’t want the horse to be stuck in his lower, survival-based brain. We don’t want to dominate or control him; we want him to learn to appropriately control himself.

The most effective trainer neither coerces nor placates the horse. Instead, she uses well-timed pressure and release to have a conversation, with a goal of mutual understanding, trust, and connection. To succeed at this, she must be able to regulate her own internal state, in order to help the horse learn to regulate his. She does what’s right for the relationship, and the horse learns to do the same.

When horses learn to slow down, think, and freely choose to do the right thing, they become not only happier but better at their jobs, whether competing or trail-riding for pleasure.

Connecting in Everyday Life

Although Natural Lifemanship arises from a framework of healing trauma, it can help everyone. We all benefit from enhanced self-awareness and self-regulation. We all benefit from relationship-building skills. Through this work, we can learn to stay calm and grounded when faced with challenge; to enjoy more fully those moments of connection with others, and to create the most fulfilling relationships possible with people and animals.

A Few Takeaways

Make connection the priority.

Whether talking with coworkers, walking your dog, or working out a disagreement with a family member, prioritize connection and you’ll get a much better outcome. Rather than fixating on issues, trying to control others, or insisting you’re right, try to connect. This approach leads to considerate listening and more genuine self-expression—which make for better immediate experiences and healthier relationships.

Plus, connection feels good; it cultivates wellbeing for yourself and those around you. As you go about your day, remember you can connect with others even in casual interactions.

Do what’s right for the relationship.

Let this principle guide you in your relationships with people and animals. Do what’s right for the relationship, and ask the other to do the same. This means you’ll communicate what you need and be aware of the other’s needs. You’ll make your own requests and listen to theirs.

Be aware of how much pressure you’re using.

When you communicate with others, be aware of how strongly you’re coming across. Think about what constitutes pressure in a given situation, and be mindful of how you apply it. Use the least amount of pressure necessary to get a response. And make sure you learn how to take the pressure off when you need to! (To learn more about this, you can attend a Natural Lifemanship Training.)

Cultivate your self-regulation.

In order to make use of these ideas, you need to be able to regulate your own system. Like well-traveled paths in the woods, the brain pathways we repeatedly use become our go-to reactions, while the ones we don’t use wither away. Notice your habitual thoughts and reactions. Learn to pause. You might make some subtle shifts that have a profound effect on how you feel and how you relate to others. A daily meditation practice can help.

Natural Lifemanship is both a science and an art. It helps us heal and evolve so that we can, in turn, have a positive impact on those around us. And the bottom line is, it just feels better when we live by these principles.

See more, and meet the horse-celebrity Grappa, at GrappaLane.com.

Find Natural Lifemanship trainings in your area.

by Kathleen Choe | Feb 16, 2018 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Case Studies, Testimonials & Reflections

How Cross Brain Connections Literally Saved My Life!

In this blog, I will discuss how a healthy brain develops and how trauma impacts this process by localizing neural connections in the lower regions of the brain, the part concerned with survival. I will share ways we can capitalize on the brain’s neuroplasticity and capacity to heal with strategies to increase cross brain connectivity, ending with an example of this from my own personal experience of being assaulted on two different occasions.

There is a great deal of discussion in Trauma-Informed Care about cross brain connections, neural pathways that connect throughout the different areas of the brain, leading to a greater capacity for self-regulation and smooth emotional state shifting in response to environmental cues. Brain development begins in utero, developing sequentially from the bottom to the top and from the inside out in response to sensory input. The first part of the brain to develop is the brainstem, which is responsible for regulating autonomic functions like heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, body temperature, sleep, and appetite. We generally do not have to think about these functions unless something goes wrong with them (during an asthma or heart attack, for example). The brainstem, which as its name suggests, is at the base of the brain, is responsible for basic survival and is where our fight, flight and freeze responses originate in response to a trauma trigger.

The next region of the brain to develop is the diencephalon, which regulates motor control. (When the freeze response is triggered by the brainstem it indicates that the diencephalon, as well as all of the regions of the brain above it, have essentially gone “offline”). Following that is the limbic system, which regulates our emotions and makes us capable of attachment and relational connection. The last part of the brain to develop is the neocortex, which allows for abstract and concrete thought, impulse control, planning and other aspects of executive functioning. The neocortex may not be fully developed and functional until well into a person’s second decade of life.

Trauma can be defined as input that is arrhythmic and unpredictable. If a pregnancy is unwanted, or the mother is in a chaotic environment due to poverty and domestic violence, or she struggles with a mental disorder or uses drugs, for example, the fetus is exposed to a barrage of arrhythmic sensory input in the womb. The mother’s heart-rate may be irregular, the cadence of her voice may be harsh or distressed, and her body may be secreting stress chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline that acid washes the womb for nine months. The part of the brain that receives the most sensory input will be the most well developed, as the neurons flock there in response to continuous activation. A baby experiencing intra-uterine trauma of any sort will be born prepared for survival, with most of his or her neurons clustered in the lower regions of the brain. A baby whose gestation was full of rhythmic, predictable sensory input from his mother’s well-regulated heartbeat, calm voice, and soothing chemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin, will be born with up to fifty percent of his neurons having migrated to the neocortex, ready for language and learning. Intra-uterine trauma primes the baby’s brain to form local connections in the lower regions of the brain in anticipation of being born into a chaotic, unpredictable environment. The foundation for future development is compromised, and any subsequent trauma layers on top of this shaky substrate to create a brain muscled up for survival and reactivity, with few cross brain connections allowing for a regulated, integrated response to environmental or relational stimuli.

Dr. Bruce Perry points out that trauma interferes with what he terms smooth “state shifting,” referring to the ability of the brain to communicate between all of its regions to come up with the best response to deal with the situation at hand. Healthy brain development allows a person to accurately interpret input and respond appropriately based on what is actually happening in the present. In the case of a car careening into your lane of traffic, the amygdala sounds the alarm in the limbic system, the diencephalon kicks in and prompts you to quickly maneuver out of the way, and the brainstem briefly shuts down unnecessary functions like digestion that would divert energy away from dealing with the crisis. The neocortex, which would unnecessarily delay the response time, essentially goes offline. Whether the car barreling towards you is a Mercedes or a Chevrolet is completely irrelevant to your survival. Determining the color, make or model of the vehicle occupies precious time and attention that keeps you in harm’s way longer than necessary and compromises your ability to keep yourself safe. When cross-brain connections are absent, and the different regions of the brain lack neural pathways to communicate efficiently, the array of responses a person has is limited. A traumatized individual might get stuck in his brainstem, lose access to his diencephalon, freeze, and be unable to turn the steering wheel, incurring a collision with the oncoming car.

This is essentially what happened to me when I was assaulted in my early 20’s in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. I was using a public restroom when a man who apparently had been hiding in the stall next to mine burst under the dividing wall and attacked me. I completely froze. I could not move, cry out, or think of how to defend myself. I never reported the assault or pursued any kind of help afterward. I simply left it buried in my brainstem and used my already active eating disorder and dissociative pathways to cope. When I unexpectedly became pregnant with my first child three years later, I realized my unhealthy patterns were going to affect my baby in damaging ways. Facing the huge responsibility of carrying and then caring for a child provided the incentive I needed to pursue healing in so many areas of my life. Although I worked hard on my recovery, my very stubborn pathways for dissociating from strong emotions and avoiding what I perceived to be the dangers of intimacy remained strong.

When I discovered Natural Lifemanship, I knew these principles of relational connection and partnership were the missing pieces to my healing puzzle. I was initially dismayed to find how much I struggled to experience connection in the round pen with the horses, but as I kept practicing asking for attachment and detachment, I found over time that I was starting to feel my emotions and body sensations more consistently and accurately, both with horses and with people. Through both ground (Relationship Logic) and mounted work (Rhythmic Riding), I strengthened the cross brain connections necessary to stay regulated and grounded without checking out in stressful situations. My sense of peace and confidence and ability to stay present and connected to myself continued to grow.

Last year all of this was put to the test when I was out running in my neighborhood early in the morning. I heard footsteps behind me on a narrow stretch of sidewalk bordered by tall hedges and a railing on either side and turned sideways, thinking another runner wanted to pass me. Instead, he grabbed me by the shoulders, muttered the word “sorry” and threw me to the ground. My brain immediately went into gear. Just the night before I had shared a public service announcement from the Austin Police Department with my running group concerning a sexual predator who had been assaulting female runners. I could literally see the list of suggestions in my mind and began sorting through them. “Make noise,” my brain said, and I started screaming as loud as I could. My assailant covered my mouth with his hand. “Fight back,” my brain commanded, and I shook one of my arms free and tried to push him off. As he tightened his grip, I remembered, “Strike where he is most vulnerable,” so I started reaching towards his groin area as best as I could. His eyes widened in surprise and he suddenly let go of me, slamming my head into the pavement. I don’t know how long I lost consciousness, but as I came to, I heard a voice shouting, “Get up! Get up! You have to get up NOW!” I realized the voice was my own; it was my brain, telling me I needed to mobilize in case he came back. I was able to get up and wobble up the hill until I met another runner who took me to her house and called 911.

I reported this assault. I went to the emergency room, made a statement to the police, and described the suspect to a forensic artist who captured his likeness quite accurately. I engaged in therapy, and spent hours in the round pen with horses, crying, connecting, and healing. I shared my experience with my running group and put together a tip sheet for runner safety, which I shared with other running groups in the area. I attended a self-defense class. Despite the temptation to revert to old patterns of dissociating from my fear and pain, I practiced feeling all the emotions in the aftermath of this trauma, letting myself weep when the detective called to say my suspect’s DNA was found on another victim. I gave myself permission to be scared, sad, and also proud. Proud that I had done the hard work to develop the cross brain connections that allowed me to fight back instead of freezing during my second assault. During my therapy for this attack, I was able to process my first one as well.

Cross brain connections are essential for flexible thinking and appropriate responses. Practicing mindfulness and grounding skills on a regular basis allows these neural pathways to develop and strengthen in a brain compromised by arrhythmic, unpredictable input. Research continues to highlight the neuroplasticity of the brain in response to rhythmic sensory input that allows it to heal and integrate following trauma. Expanding local connections into cross brain connections enhances our ability to experience emotional regulation so that we can build healthier, more satisfying relationships with ourselves and with others.

How does one build or repair cross brain connections?

A daily practice of mindfulness (meditation, yoga, or centering prayer, for example) has been shown to improve brain connection and functioning. Exposure to reparative or corrective relational experiences also contributes to building neural pathways from the lower to the upper regions of the brain. Trauma victims often repeat dysfunctional patterns in the relationship due to compromised neural connections in the brain, reinforcing their trauma pathways. Equine Assisted Psychotherapy involves partnering with a horse to provide opportunities for new pathways to form a healthy relationship is built between horse and human under the guidance of a therapist and equine specialist. Clients learn how to build and sustain healthier relationship patterns as their brains literally re-wire through the experiential component of the therapeutic work with the horses. Through a combination of ground and mounted work, a person can learn self-regulation skills, positive coping resources, and begin to heal from their trauma.

What are cross brain connections good for? At some point, they just might save your life.

For more information, check out the following website: naturallifemanship.com

*Dr. Daniel Siegel’s Wheel of Awareness is an excellent resource for developing such a practice, as is St. Michael’s Hospital Awareness Stabilization Training.

by Kate Naylor | Feb 7, 2018 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship

Typically, when we think of objectification we think of the overtly negative kind. Women’s bodies as objects for other’s consumption, children as extensions of ourselves, or the Earth as a disposable resource for our own benefit. Yet, a more subtle objectification is alive and well in human nature – that is, the deification of someone or something, the act of putting someone not below us, but above us and on a pedestal.

This can be seen clearly in the equine therapy world, where there seem to be two opposing camps at odds with each other. One believes horses are a useful tool for the healing and growth of humans – the other believes horses to be wise beyond measure, bordering on otherworldly, and having unknowable gifts to offer us.

The “horse as a tool” camp has a long history; throughout their generations, horses alongside human beings have been work animals. They carried warriors into battle, pulled farm equipment, were a mode of transportation, and then more recently, a source of recreation. None of these activities with horses lends itself well to seeing them as sentient beings. To care for them and think about them as we do a human would interfere with the work. And generally speaking, humans also have a long history of seeing animals as fundamentally different from us; they couldn’t possibly share in our experiences, feelings, and needs. Much of horse training reflects these beliefs – domination, power, and control continue to be the go-to for working with horses, no matter their job. For this camp, horses are considered less intelligent than humans, less capable of self-control/self-determination, and certainly in need of our leadership. In equine therapy specifically, this plays out as horses being a facilitator for therapy and not much more. They are an object for practicing leadership skills, setting boundaries, for guiding through obstacles; and when the horse listens and does what he is told, we humans feel strong and confident. Also in the “horse is a tool” camp, there is the horse that isn’t even a horse – he is a representation of my angry father, or my cold mother, or my demanding boss. He doesn’t necessarily have to do anything to make me feel that way, I just feel it because I needed to – and the horse was there to embody those feelings for me. It’s easier to project onto him than onto an inanimate object, like in the empty chair technique commonly used in office therapy – and easier to project onto him than a real person, because a person is inclined to express their own thoughts and feelings that don’t fit for our projection. The horse’s feedback then, his own experience and behaviors are not often taken into consideration – it would give him more dimension than would be helpful in the “horse as a tool” paradigm. He is something of a chess piece moved through a session in order to produce feelings or reactions in the human client. His presence is very useful, but he is not an individual and there is no dual-sided relationship there. The relationship is all on the human’s terms.

In more recent years, thanks to science and some evolution of thought, we are beginning to be reminded that humans are also animals, and perhaps not that different from those who surround us. More consideration for the welfare and internal lives of horses has arisen – a very good thing. However, it seems we are overcorrecting a bit, and now witnessing another camp forming. Or actually, simply growing in prominence – as this camp has been around as long as the first, really, but gaining traction in this new attempt at honoring the horse. This second camp sees horses not as tools or mere utilitarian devices, but as powerful spiritual guides, insightful creatures with gifts for healing. In this camp, horses are mystical, operating on another plane of existence, and here to give us messages that our limited human brains cannot detect for ourselves. They are, in a sense, deities walking among us. Some would say this is a beautiful correction to the idea of horses’ as lesser beings and tools for our use. But, to me, this is simply the other side of the same coin.

If a horse is a tool we use him for our benefit, and often miss the real flesh and blood animal standing in front of us. We see only our desires for him, our own goals, our own path. We control him to practice leadership or we project onto him to provide catharsis, and we worry very little about his own desires and needs. We don’t take in his presence, his behavior, as information on how we can change to be in better relationship with him, this specific horse. We miss that he is perhaps checked out, or stressed out, or confused and irritated – because we just want him to do what we ask, or represent someone he is not. But the flip side is not much better – here’s the thing, if a horse is a sort of a god – a creature capable of telepathy and mystical healing, he is STILL an object. In this camp, much value is placed on the act of just being with horses. It is often argued that simply sitting with them provides healing, growth, and insight. Now, as a horse lover myself I can honestly say there is something lovely about sitting with horses. There is a peacefulness there, and much like meditation, when I am still and peaceful I have clarity of mind. But to say the horse, while grazing and drinking water and pooping on the ground, is sending me messages from others on another plane of existence, is telepathic somehow, is to continue not seeing that horse, for who he is. He is still an object, a representation of my inner world. (Not to mention, feeling peaceful while sitting with horses may feel nice, but it is not therapy. We cannot ethically call this sort of work psychotherapy, we cannot bill insurance, and we certainly cannot be taken seriously by the psychotherapy and medical fields. Feeling peaceful momentarily or experiencing catharsis does not equal therapeutic growth. )

There is a fine line between being spiritual and twisting spirituality to suit ourselves. This treatment of horses crosses that line, frequently. I by no means intend to suggest that a spiritual connection with a horse isn’t possible – on the contrary, I firmly believe it is. But, I have seen time and time again this desire for a spiritual connection taken to an extreme that renders horses one-dimensional, and even more upsetting, continues the destructive paradigm of power and control – the exact paradigm this camp set out to destroy! When the horse is simply a conduit, a reflection of our inner world, or a creature on a pedestal, we still control him. We decide what he tells us and when, we decide what his behavior means to us. We go to him when we need something from him, and think little of how our interactions could be mutually beneficial from his perspective. What disturbs me about the blending of the spiritual with horses is I rarely hear of someone getting a negative message from their horse. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard people speak of communing with horses and receiving the message, “I don’t really want to be around you, will you go away?” – and yet, I see horses respond to people, through their behavior, with this exact message frequently. So what’s happening here? To me, it is the disconnect between reality and human projection. We want to control the information we receive. No one wants to hear that they are a mess and not fun to be around. But, spirituality, when it is done in the search for wholeness, has real darkness to it. There is brutal honesty, grief, and unpleasantness when we dig deep – as well as the good. If your spiritual connection with a horse is all telepathic sunshine and rainbows – it might be worth questioning. It’s scary to release control of both sides of the relationship, but it is also where the real, tangible healing happens – healing that can be carried forward into new relationships.

Horses are animals, mammals, similar to us in some ways and different in others. They have their own desires, their own needs, and their own priorities. We, over the centuries, have domesticated them and insisted they live alongside us. The least we could do is learn about their communication, their behavior and do our best to see each of them as an individual. Whether we see the horse as a tool or an otherworldly being – what ultimately suffers is the therapy, and the horse’s welfare. (Keep an eye out for blogs on those topics later).

Until proven otherwise, what we currently know is horses communicate through body language – the combinations of tension and relaxation, ear position, movement, and more. In a therapy session, when a horse leaves us to go drink water – is he telling us that our soul is thirsty and it’s time to take better care of ourselves, or is he rejecting our attempts at connection just like our mother…or is he simply an animal that needs to quench his own, literal, thirst? Which one is based in his reality, and which one is something we decided based on what we wanted to hear/feel/see in the moment? Not to mention, what does this do to the therapeutic growth of the client – to ignore a simple behavioral choice and pile countless meanings on it instead? To interpret behaviors as more than their face value? To expect telepathy? Have you ever experienced that real desire for your spouse to read your mind? To just know you wanted or needed something without having to ask…and for those of you who have been with a partner for a long time – how often does this telepathy occur? For my clients, this sort of thing is often what landed them in relational difficulties in the first place – mind-reading, meaning-laden interpretations of behavior, projection. These are road blocks to true connection – love based on reality, intimacy, authenticity. I, for one, do not want to recreate these unhealthy patterns in my therapy sessions, and therefore, cannot try to control the horse, dismiss the horse, or deify the horse.

The thing that makes me the saddest about these two camps, besides the possible damage done to clients and horses – is that both are missing out on the very real relationship that is possible. I can’t have a connected, nourishing, and challenging relationship with an object like I can with a sentient being. And in therapy, a lack of real relationship restricts significant opportunities for lasting healing. This is different from the cognitive shift that can happen when I see my mother in the horse’s behavior, or lead a horse through an obstacle course, or hear wisdom from within when I sit quietly watching horses graze. None of these activities require the horse to be a sentient being, a unique individual – this same work is being done with furniture in an office, or drawings, or solitary contemplation. And while, of course, these activities with horses can be beneficial, it is difficult for these benefits to last. For lasting change, our brains and bodies have to practice a new way of being – insight alone is not enough. Consider how many people you have met who know the right things to do, and simply can’t do them consistently (myself included!). The beauty of the horse as a sentient being, a partner in therapy, is that I can build a real two-sided relationship with him. I can try to engage, ask things of him, have him ask things of me; I can make mistakes and see the horse’s negative response, and then I can repair those mistakes and see the horse’s positive response. It’s harder, and it’s more vulnerable. There are moments when I will be greatly humbled, and moments when I don’t get what I want. But, it’s also real. With time, I can learn his preferences and he mine – and we can navigate the difficulties of boundary setting, intimacy, listening, and asking. I can learn, deep in my bones, how to be in a healthy partnership where we both heal, and then I can practice it each time we are together. And when I do that, I can go back to my human relationships with new ways of being, not just thoughts. My human relationships transform – and isn’t that the ultimate goal of therapy with horses? To heal not just in session, but out in the world too? But none of that is possible if this specific horse, with his specific temperament, isn’t truly seen for who he really is. Not for what he represents and not for what he can do for me.

Some folks may assume I mean that these two camps aren’t ever doing good work, or that there is malice in these approaches. Neither is fully true. Good work can be done, and it is human nature, not evil, to try to control others and our experience. My argument, though, is that there is a third way. A way in which horses are neither less than or better than, but animals just like us; full of foibles and bad habits and grace and healing – and in this third way are both the human and horse honored for their real, flesh and blood contribution. My argument is for letting go of controlling the other, so we can see what is really there, right in front of us.

by Reccia Jobe | Feb 7, 2018 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Horsemanship

You’ve all seen them; those kitschy t-shirts, hats, and signs that proclaim, “My horse is my therapist.” I openly admit, I’ve contemplated buying one of those before or making a sign of my own with this endearing saying for the barn or my home. I liked it. It hit home for me. I felt it concisely and cleverly conveyed the feeling of appreciation and gratitude I feel for what not only my horse has done for me, but for what hundreds of horses I’ve worked with have done for me and so many others. To be frank, I didn’t actually think about it too much. I felt something about it, my left brain filtered it into the “good” category and I moved on from there. I never bought a shirt or hat or made a sign, but it remained in that “good” category in my brain until recently.

I haven’t noticed the saying pop up anywhere in a long time, but just a few days ago, I heard someone say it in passing. I didn’t notice any kind of new thought or feeling about it as I heard it, but I noticed a sensation in my gut. Since I’ve been working diligently the last few months to become more connected and in tune with my body, I was immediately able to recognize that sensation as a warning signal. This particular signal usually means something feels unsafe, incongruent, or off in some way. I was busy with something else that needed my attention at that moment, so I simply took note of my body’s response and set it aside for later reflection.

What about that saying would cause a visceral response from me? Once I had a moment to reflect, it took probably .22 seconds for me to find the answer. You might think I’m exaggerating, but I’m not. See, when I open the door for the higher regions of my brain to listen to and connect with the signals coming in from the lower regions and my body, it literally takes my brain that long to process the information. Well, no one has scanned MY brain and measured it, but neuroscience says that’s about how long it takes in a human brain, so I think it’s a pretty fair estimate to say that’s how long it took mine to come up with the answer. And it’s a simple yet complex answer.

The simple part- my horse is NOT my therapist. My therapist is my therapist. My horse is my horse. (Hmmm…I like that saying. Could this be the next NL t-shirt?) The complex part- I feel good when I am around my horse, which can actually be very therapeutic for me. But that doesn’t make it therapy. Seriously, have you ever been to therapy? I have and I can say when I get in the weeds and start doing the hard work on myself, it does NOT feel good. Let’s say it doesn’t always feel good when I’m working with my horse because I do have to work on myself in the process. It can still feel like therapy when I am with my horse, which can feel like my horse is conducting therapy on me. But she’s not. She’s just being a horse interacting with a human. Just like my dog is being a dog interacting with a human when we are together. Just like my dad is being a human interacting with his daughter, and my brother is being a nuisance..err.. I mean, human interacting with his sister, and the cashier at the grocery store is being a human interacting with a customer. And since I have come to learn to see horses as beings just as capable of making requests and choices for healthy relationship as humans, I just can’t tolerate that saying. It makes me sick to my stomach because for me it is the same as saying my dad is my therapist. Say it out loud and tell me that doesn’t make you cringe. And what about my brother is my therapist? Sound good to you? Now try this one- my cashier is my therapist. Ok, so that one makes me giggle a little, but only because it sounds so absurd!

Being steeped in horsemanship and traditional horse training methods, I understand how this saying came about as we humans have a long history of projecting onto and objectifying animals. I see how it could be argued that giving your horse therapeutic powers even though he never completed high school, is an enormous leap from how horses have been treated historically by humans. That’s probably why it got filtered into the “good” category in my brain years ago. But making your horse your therapist is still objectifying, it’s still projecting, it’s still using your horse. So, let’s take the next leap in our development as human beings and figure out how to interact with horses as what they actually are…horses. To learn more about how we do this at Natural Lifemanship, visit the Start Training link or view our online videos and content.

Recent Comments