by Jamie Morley | Apr 20, 2019 | Applied Principles, Case Studies, Testimonials & Reflections

In December 2017, I attended my first NL Intensive training in Brenham, TX. I’m pretty sure it was day two, which in my experience at these trainings, is when things really start getting stirred up internally. This life lesson came to me in my blind spot. Like a horse’s blind spot, it was right in front of my face (or maybe right behind my rear?). In fact, the only one who could see what was going on was my partner for the weekend.

I was in the round pen with the horse, Indigo (name has been changed for this article), trying to connect through attachment. When we had worked together the day before, we had a pretty quick connection, so I figured it would happen pretty easily again. This was not the case. Indigo was completely ignoring me. So I started to gradually increase my efforts, going from clucking and calling her name, to stomping my feet, to waving my hands in the air, to getting closer and jumping up and down and waving my hands all at the same time.

My partner stopped me (thank goodness!). I walked over to her and took a much needed break from all the jumping and flailing around. She said something simple like, “It seems to me like your energy on the outside does not match your energy on the inside”. At first I shot a quick answer back like, “Really? I feel like all of my energy is as high as it can go! I don’t know what else to do.” And then the thought settled somewhere deep within, and I took a deep breath and looked at her. She was right.

At some point, Tim Jobe had joined the conversation (he has a way of popping in at the just the right moment). He asked something to the effect of, “What might be keeping you from raising your internal energy?” I explained that it felt like there is a line that divides where I feel safe and comfortable to make an “ask” in a relationship and where it feels all together too risky and vulnerable. Tim asked, “What is the risk if you cross that line?” I started to process out loud about how if I gave more energy toward the relationship, what if it wasn’t reciprocated? What if she still kept ignoring me? The fear of losing what connection I did have seemed to outweigh the potential of gaining an even deeper connection. A wave of realization was rushing over me. This, of course, directly correlated to how I often felt in my human relationships.

Then something beautiful happened that I’ll never forget. By this point, I was back to standing in proximity to Indigo. As soon as I acknowledged my true inner feelings to Tim and my partner, Indigo turned and came toward me. She planted herself right there next to me as tears began to steadily stream down my face. I hadn’t even asked her to come over. She chose to all on her own. And all I could do was stand there next to her and let the tears fall freely. I savored that moment with her and all that she “said” to me through her actions.

In a way that only a horse can, she affirmed so many truths for me in this moment. She affirmed that all she wanted was the real me. She didn’t require that I had it all together. She only required that I was being real with myself and with her. It was as if she was saying, “Oh good, you’re truly present with me and now I want to come be with you”. She also affirmed that the experience of a connection like this was totally worth the risk and vulnerability it took to get it.

“Most people believe vulnerability is weakness. But really, vulnerability is courage. We must ask ourselves…are we willing to show up and be seen?”

–Brene Brown

Self-sufficiency has met her match, her name is Vulnerability. It’s only through vulnerability that true connection is experienced. Self-sufficiency may give a false sense of security, but it will forever leave me feeling disconnected from others. Indigo helped me realize that what I want more than independence and self-sufficiency is the sense of being known and accepted for who I am. In order to get this, I have to show up in relationships as my authentic, vulnerable, messy self.

Every day we have the choice. Today I choose vulnerability.

—————————————————————————

Jamie offers life coaching, both equine assisted and non-equine, to the Central Ohio area. She is dual certified through Natural Lifemanship as a Practitioner and an Equine Professional and is a certified Life Coach through the JRNI Catalyst Coaching Intensive. Her coaching business, Hope Anew, thrives on this motto: Healing Occurs through Purposeful Elements- Art, Nature, Environment, and Well-being. She loves taking creative approaches to helping people on their path to personal growth, as the path to transformation looks different for everyone!

by Michael Remole | Dec 10, 2018 | Applied Principles

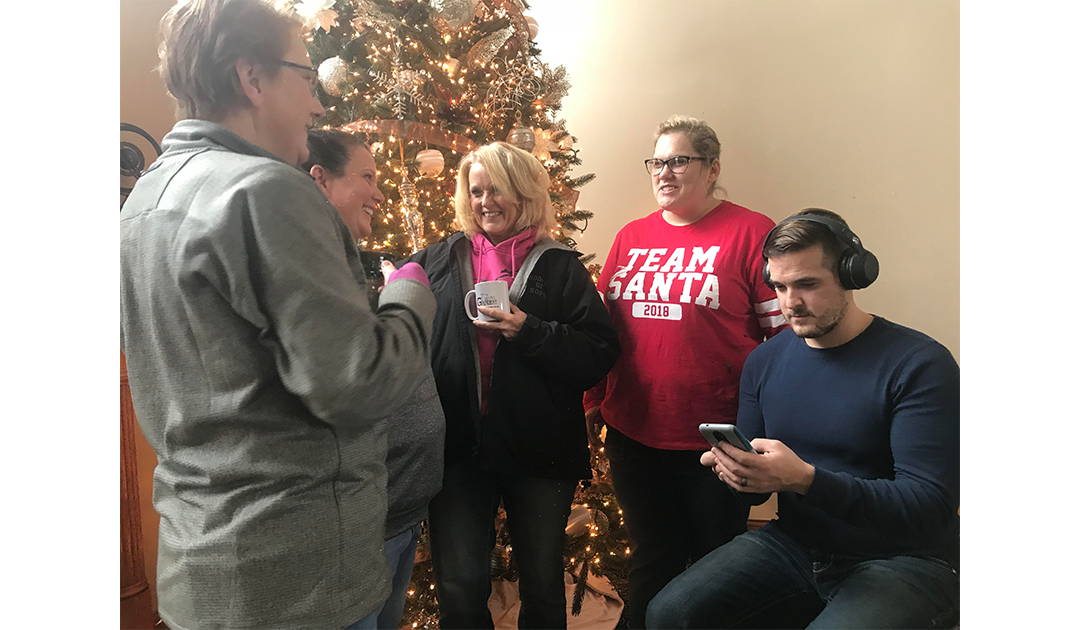

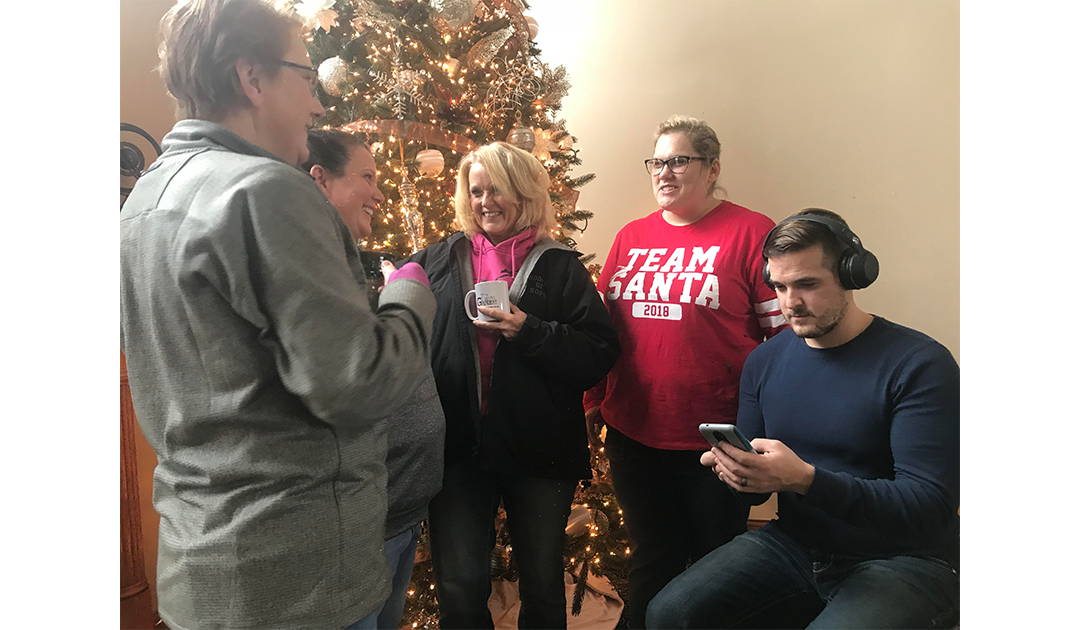

For some, the holidays bring joy and a rich connection with family, friends, God, and memories of holidays past. For others, holidays shine a bright light on grief, loneliness, and disconnection. With the holidays approaching, I have been thinking more about connection and. . . technology. It isn’t news that technology has made real human connection much more difficult, in many ways. The older generations shake their heads and say, “back in the day. . .,” BUT I also think technology has something to teach us about human connection. I hope you enjoy my musings.

I have grown to really love my Bluetooth noise canceling headphones. I wear them when I head to the gym to work out, go for runs or walks, and even when I mow. It is so simple. Press the power button and a lovely voice comes on and says. . . “connected”. I did not realize the power of that phrase until just recently when I had forgotten I turned off the Bluetooth option on my phone.

I have a morning routine of driving to the gym, staring at the entrance of the gym (thinking that maybe I can watch someone else workout and get the benefits), and then deciding to put on my headphones, get into gear and hit the gym. However, this particular morning, as I sat in my car following my usual routine, I hit the power button for my headphones and waited. . . then I waited some more. . . I shut the headphones off thinking something was wrong with them. Then, I turned them back on and. . . waited again. I sat waiting for that lovely voice to tell me I was connected. That’s when it dawned on me that I must have done something to my phone. So, I went into the settings, hit the Bluetooth button and. . . waited some more. When it began telling me it was “searching for device” I realized that something must be wrong. Why is my connection taking so long? What is wrong with the phone? What’s wrong with the headphones? That’s when I realized that this amazing Bluetooth device was helping me understand a bit more about connection. For countless weeks, I had gone through the same procedure to ensure the phone and the headphones were connected, yet today something was different. The connection had failed and it took some work to fix it. That’s when I began to see just how much the struggle with the connection applied not only to my headphones but also to my life.

I had taken for granted the connection between my phone and headphones. It was usually easy. With the click of a button I had connection. However, on this occasion, it was not easy. In the midst of my frustration, I began to ponder just how difficult healthy, genuine relational connections really are. They take work—hard work. I have been spoiled in life by how quickly we can connect to things—WiFi, TV, cell phones and various Bluetooth devices. I began to wonder what these things are incorrectly teaching us about connection?

I was finally able to connect my phone and headphones and complete my morning workout. However, in relationships, connection is not always guaranteed. What do we do when the connection with self or someone else appears to be “offline”? How do we troubleshoot when connection with self and others doesn’t seem to be happening like we thought it should? As I wrestled with these thoughts, I began to realize that we have several options. For example, I could have blamed the headphones and thrown them away. I could have gotten mad at the phone and thrown it out the window. I could have reset both the phone and headphones so they would be able to effectively communicate with one another. What is your go-to reaction when connection does not work the way you had planned?

Healthy connections are hard. It takes two willing participants to do the troubleshooting when the connection seems off. What does that look like for us? How do we troubleshoot in these situations? As we head into the holidays, here are a few of my thoughts.

Connection with self comes first. In order to have a healthy connection with someone else, I must first have a healthy connection with myself. This means taking the time to get to know yourself and to genuinely love yourself. It also means that we have to take time to stay regulated. I think we’ve all experienced a Wifi connection that is super weak and inconsistent. This is a prime example of someone who needs to regulate in order to connect. I can give someone a superficial connection from a place of dysregulation, but if I want true, authentic connection, it must be done from a place of regulation. This is a critical part of my troubleshooting when connection seems off. What steps can I take to regulate myself so connection is more authentic and genuine?

During another trip to the gym while I was working out and enjoying my podcast, my headphone battery began to die. As the podcast continued, the headphones would say “please charge device.” It said this for several minutes before the headphones powered down. Sadly, my workout quickly ended so I could hurry to the car and recharge the headphones. Another valuable lesson about genuine connection. . . In order to have a connection you must keep your “battery of life” charged. I can try as hard as I want to connect the phone and the headphones, but if either device is low on power, the connection just won’t work. How is your “battery of life”? What are you doing to recharge your battery so you are more capable of genuine, healthy connections?

Years ago, an incredible movie called “What About Bob?” came out. In the movie, Bill Murray likens relationships to phones. Sometimes the phone is out of order and you need to try again later. Sometimes the phone is cut off and there is no chance of getting through. This approach is applicable here in regards to connection. At times, the connection may be offline due to the other person needing to do his or her own work. When this occurs, we simply note that we should take care of ourselves and try that connection again later. Then at times we come across relationships that are cut-off and it’s time to recognize that trying to connect in that relationship is not healthy.

In a society of instant gratification, we are accustomed to quick “connections”. Recently, I was talking on my cell phone and I happened to walk by my car that I had just started. As I approached the car, my phone connected to the car while I was standing outside the car trying to continue the conversation. I had not asked for that connection, it just happened. On other days, no matter what I try, the phone and car will not connect! I am sure that you can relate and get frustrated as well when one device won’t connect with another. In those moments of frustration, let’s pause, take a deep breath, and reflect on what we are doing to better connect with ourselves and with others. Let’s take those moments of reflection to help us become more capable of having healthy, genuine connections with self and others. If we fail to do this, we will hear “searching for device”. My hope is that this holiday season we will hear a lovely voice saying “connected” as we truly connect in the relationships that matter the most.

Learn more about Gateway Family Services.

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Apr 2, 2018 | Applied Principles, Personal Growth

As I ponder this Easter weekend, I am reminded that miracles happen. . . and that usually they don’t just happen.

To receive a miracle is more than passive acceptance of something wonderful. Miracles require work. They require relationship. They require surrender. Miracles require that the recipient of the miracle take enormous risk, and this risk, in and of itself, is transformative. The learning and, oftentimes, deep pain that comes with the decision to risk, changes us in profound and beautiful ways. I believe miracles are the result of Divine intervention. . . absolutely! They’re also the result of a two-sided relationship with our Creator.

The last 5 years have opened my eyes to miracles all around me. When I see a miracle I see my Creator at work. Yes I do. I also see risk. I see the massive vulnerability and bravery that comes with taking the risk a miracle demands. I see years of hard work and preparation and then I see the grueling labor and love it takes to really live out our miracles. I see belief in the impossible. I see an acceptance of our own inadequacies and need for support.

However, I have also experienced times when the Divine is ready for a miracle, but we are not. I am learning to recognize miracles each day, and to pray for the strength, grace, and wisdom to embrace miracles offered and grieve miracles lost.

As we work in this field, I am humbled by the passion that exists among people making the world a better place for all living beings – the people with whom we work every day! The miracles needed for our clients, our animal therapy partners, and for our businesses bring tears to my eyes. As we give and give to others the miracles needed in our personal lives is staggering. It is my hope this Easter Monday that we all have the strength to walk in a world of miracles in a way that profoundly deepens the relationships for which we were created.

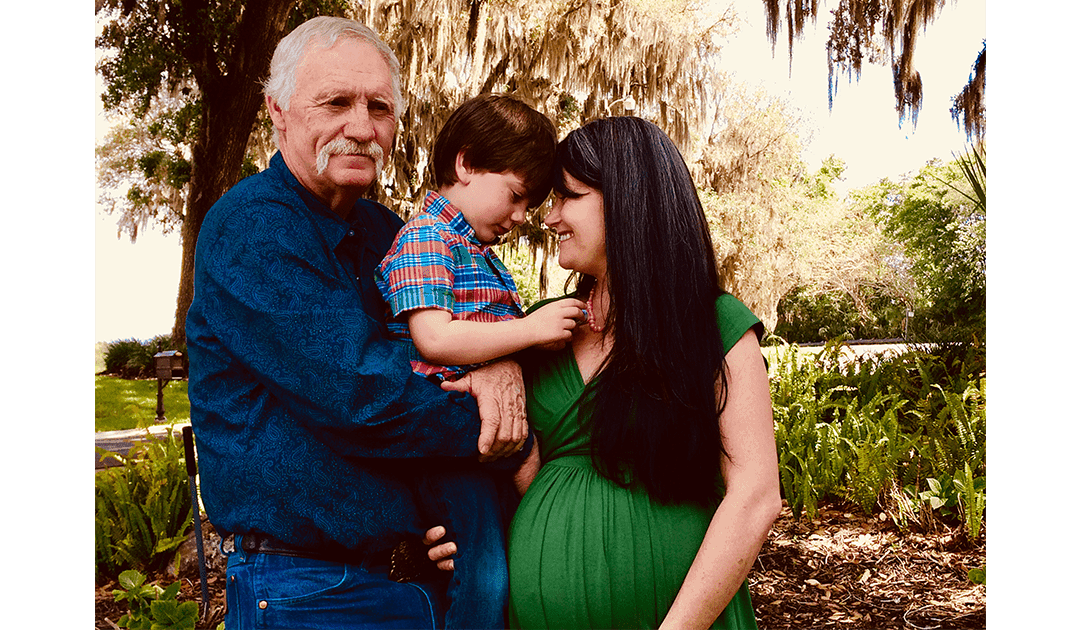

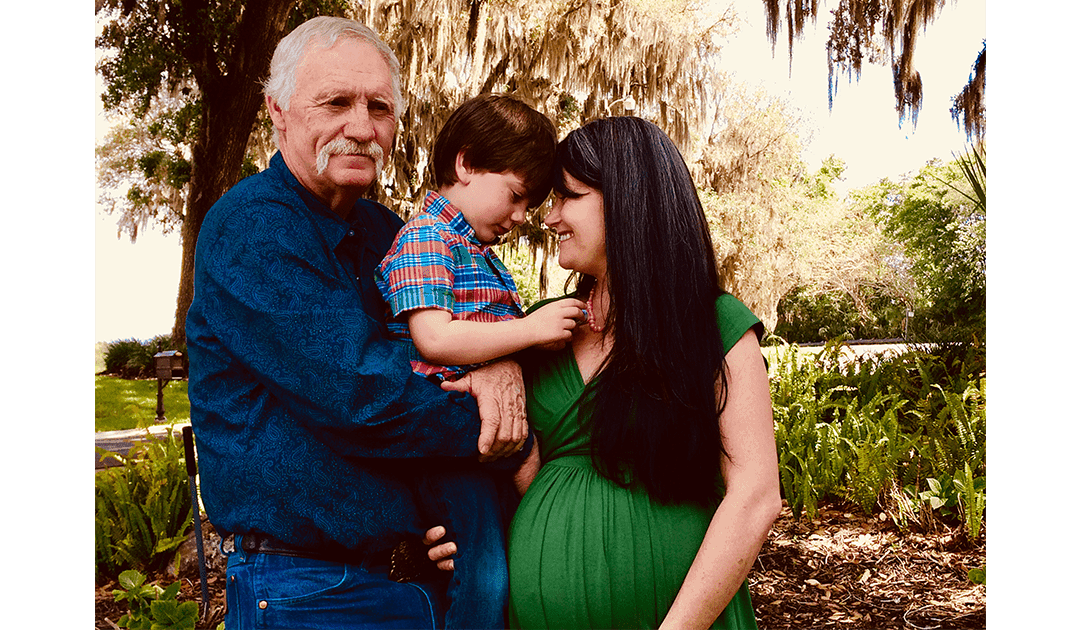

Happy Easter from our little family to yours.

by Tim Jobe | Feb 2, 2018 | Applied Principles

I read a study the other day that talked about the way the brain functions when our fundamental beliefs are challenged. Basically, it stated that the same regions of our brain fires when we are physically threatened. Those regions that fire on both occasions are the regions responsible for our survival. Although the author was studying the ramifications of political beliefs, I think this has some very important implications for many areas of our lives.

At our Natural Lifemanship trainings we operate out of the belief that a horse is capable of learning how to appropriately control himself or herself. This goes against a lot of peoples’ fundamental belief system, especially if they have extensive experience with horses. Many of the people that have attended our trainings have had to change that fundamental belief to use our model of therapy. It requires changing pathways in our brain and can be an excruciating process. I want to personally thank the people that have been vulnerable enough to struggle with that change. I am excited that 2018 brings us many more opportunities to help people make that shift. I know it will be life changing for the horses and clients we work with, as well as for ourselves.

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Feb 1, 2018 | Applied Principles, Personal Growth

Secure attachment to this moment is about finding safety, security, and perfect acceptance of what is, while still being free to miss what was, and long for what will be.

In 2017 I was given the opportunity to practice one of the more difficult principles we teach in Natural Lifemanship – Secure attachment is only found when we are able to feel an internal sense of connection during attachment with AND during detachment from important relationships. The possibility that we can experience a deep sense of connection to others when we are physically alone is, oftentimes, difficult in theory and in practice. I will share my personal story of growth, change, transformation, grief. . . and loss…extreme loss, and how our child helped me better understand that secure attachment extends beyond the relationship with self and others. We can also seek to find a secure attachment to this life and this moment, in general. We can be “securely attached” to a thing, an idea, a moment, a belief. . . Secure attachment extends to “what is”, and that requires the ability to be connected to not only what is right here with us, but also what is gone, or not even here yet.

In Natural Lifemanship (NL) the way we conceptualize secure attachment, connection, attachment, and detachment are important. Specific language and concepts help people effectively transfer learning organically and seamlessly between species and space. This language also provides the space for abstract human concepts to become more concrete and physical, oftentimes making them easier to internalize. Many times in NL physical concepts have an emotional counterpart and vice versa. Attachment can be equated to the sharing of physical space. Detachment can be thought of as exploring physical distance. Both attachment and detachment can exist when there is a concrete felt a sense of connection, as well as an internal sense of connection. Alternatively, a sense of aloneness can prevail regardless of proximity. Children and adults with a secure attachment pattern are able to feel connected and secure in their intimate relationships, while still allowing themselves and their partner to move freely (detachment). It is this kind of relationship that we help people find with a horse – this is part of the reparative experience for our clients. . . and, I would say, for many of us as well.

More about attachment and detachment in therapy sessions can be found in this blog by Kate Naylor. More about how spiritual intimacy grows through connection with detachment can be found in this blog by Laura McFarland. When you sign up for Basic Membership you gain access to more than 5 hours of video demonstrating how attachment, detachment, and connection play out in a relationship that is built between horse and human + more online learning and many other benefits. View all of our membership content here.

But I Miss The Caterpillar…

A year ago, I was reading our two-year-old (almost three-year-old) a book called “The Very Hungry Caterpillar.” On the last page when the caterpillar turns into a beautiful butterfly, our child said, “But where is the caterpillar?” I reviewed the process the caterpillar had gone through in this sweet little book we’d read many times, and he said, “But I miss the caterpillar.” We had a wonderful conversation about change and transformation. . . and loss. You see, this conversation happened about two weeks after our nanny, Carolyn – “Kiki” to Cooper – died a sudden, tragic, unexpected, and untimely death. Carolyn had been our full-time nanny, traveling with us as Natural Lifemanship was growing, since Cooper was 3 months old. She was a member of our family, and like a second mother to me in every way. She drove me crazy and I loved her dearly. She made it possible for us to work in a field about which Tim and I are deeply passionate, while still spending as much time as possible with Cooper. . . something about which we’re even more passionate. She helped us raise our child. I think I’ll just repeat that again for emphasis. She helped us raise our child. She helped me, in very practical ways, navigate this whole working mom thing. She loved Cooper and he loved his Kiki. This was a major loss for our family – couched between and among more loss. In the latter part of 2016 and throughout 2017 our family tragically, suddenly, and unexpectedly lost three more significant relationships. We lost two more the “normal” way – it was expected and it was time, and still painful. After my son and I talked about how change and transformation are often accompanied by grief and loss – in two-year-old language, of course – my little boy said, “I miss Kiki too. AND I don’t wike (like) butterflies.” At that moment, stories of Kiki walking the streets of gold, pain-free, with her mother and with her Jesus, did very little to offer me comfort. . . I must admit I agreed with my little philosopher. I do believe death is the ultimate transformation, and I wasn’t particularly fond of butterflies at that moment either!

Death is also the ultimate detachment from the ones we love, and can result in disconnection. . . or not. It takes many of us years to learn how to deeply connect with those we can see, hear, feel, and touch (attachment). It is often much harder to find that connection when we are physically separated (detachment). Connection with distance takes practice and intentionality and a willingness to sit in the pain of disconnection, for moments, instead of avoiding it. It is a secure attachment that helps us navigate detachment and loss. Typically death is much more painful when it results in disconnection. I say typically because I do realize that sometimes death and disconnection are needed for healing and closure to occur. Sometimes death makes it better. There were moments this last year that I felt this disconnection. . . those are the moments when people describe agony worse than losing a limb. . . slowly. . . without any form of anesthesia. I felt that kind of pain over the last year, many times. I felt it in the moments that I could no longer remember someone’s hands. . . or hear their voice. . . or recall their smell. Our child felt it the night he told me, “I don’t remember Kiki” and wept in my arms. At the core of much developmental and attachment trauma, is an inability to find an internal sense of connection to others when together. . . through shared space and experience, eye contact, touch. . . this transfers to an inability to feel an internal sense of connection when there is distance. Of course. I continue to muddle through the agonizing moments of detachment and disconnection. The freedom to “miss the caterpillar” guides me back to an internal sense of connection with relationships that meant so much to me, and mean so much to me. . . still. Feeling “allowed” to miss what is gone helps us stay connected, even when detached. Our freedom to grieve what once was and what will not be in the future opens us up to a connection in detachment.

However, 2017 definitely hasn’t been all about, what most would deem. . . loss. It has been an amazing year for Natural Lifemanship. We have grown, we have changed, and, I would argue, that we are in the midst of a massive transformation. I’m experiencing how these concepts of attachment can be practiced in not only relationships, but also with ideas, businesses, and moments of our lives. I have always loved butterflies. However, butterflies are sort of the end product, and they don’t really live all that long. A close friend of mine recently pointed out that butterflies get all the credit, but that the caterpillar does all the work. For Pete’s sake, The Very Hungry Caterpillar worked his little tail off to grow, and then he had to sit in a dark cocoon for two stinkin’ weeks! Time in the cacoon isn’t just a long nap, by the way. He worked hard! The butterfly’s journey is really that of the caterpillar. The growing pains of this year are no joke! Sometimes I miss the simplicity of 8 years ago when it all began. I miss the caterpillar, but I still long for the butterfly. Transformation is always predicated on the death of something. . .which means that detachment is a vital part of life and growth. If we want to be securely attached – to a person, an idea, or a moment in time – we must have an internal sense of connection when we are attached and when we are detached.

To be securely attached to the present and the future we have to maintain a healthy connection to the present, and future, AND to the past – connection to what is and what was and what could be. They all matter – that which I am attached to today and that which I have detached from – I need to be connected to both. Secure attachment to this moment is about finding safety, security, and perfect acceptance of what is, while still being free to miss what was, and long for what will be (detachment). This is at the crux of what we teach in NL. We learn to find this through the relationship with our equine partner and then transfer this way of being in the world to every part of our lives.

Our business has changed. Absolutely. We have grown up, matured, and deepened. Transformation, indeed. When Tim and I started this business almost eight years ago, we only dreamed about where we are today, but I still miss the caterpillar. Doesn’t mean that I don’t fully love and accept where we are now. Doesn’t mean I don’t long for the butterfly, but the caterpillar did a lot of work. (And still is!)

October 2017, in the midst of all this loss, Tim and I found out that we are going to have another baby! It really is a miracle of grand proportions, a welcomed gift, and. . . a surprise. We also found out just two days before our first ever conference, and before the busiest fall training schedule, we’ve ever had. Can good news come at a bad time? Well? It did for me! I am well aware of the transformative process every part of me is undergoing and will be undergoing as a result of this new life inside of me. I am also very aware of the loss. I kinda miss the naïve bliss of my first pregnancy. I long for the butterfly. I grieve the loss of the caterpillar, and I strive, each and every day to deeply revel in this beautiful moment.

This year has been all about transformation. Our three year old has recently decided that butterflies are okay. In fact, a few weeks ago he pointed to the body of a butterfly in our living room and said, “The caterpillar is still there. It’s just different.” After a long pause and a deep breath, he said, “But I still miss the caterpillar.” This past year I thought we would have to teach Cooper about grief and loss – hopefully, we did guide him through this process a bit – but he taught me about transformation and true connection. What a gift it has been to grieve with my child. Secure attachment is about looking forward and looking back while maintaining a felt sense of connection now – Just like a child builds a secure attachment through this dance of looking forward and looking back, moving toward and moving away, all while feeling the satisfaction of safety and connection to self and others. . . at this moment. I long for the butterfly and this lifelong transformative process, but I miss the caterpillar. Secure attachment in our relationships can’t exist if we feel chronic disconnection when there is distance. Likewise, a secure attachment to what is and to our future only exists when we find a healthy connection with the past. I so look forward to 2018 – the growth, the change, the transformation . . . and the inevitable loss. . . and the beautiful connection that comes in the midst of it all. I miss the caterpillar, and that is okay, because, really. . . I should. Plus, our three-year-old says it’s okay!

by Laura McFarland | Jan 31, 2018 | Applied Principles, Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Equine Assisted Trainings, Personal Growth

When we sense God is with us, our relationship with God develops through the experience of ‘connection through attachment’, which is a perceived sense of nearness. At other times, perhaps times of great loss or suffering, we may sense God is nowhere to be found. A joyful sense of connection seems to dissolve into a deep well of emptiness with no consolation. We may then experience what 16th-century mystic, John of the Cross, described as the “dark night of the soul.” In actuality, just as winter makes way for spring, this period of perceived absence and isolation potentially gives birth to an even greater spiritual resilience – an abiding sense of connection that survives even our darkest nights. We are invited into a deeper and more mature intimacy with God through the experience of detachment.

Both science and religion point to the fundamental forces and patterns of the universe as being essentially intimate and relational. While the language and the narrative may differ, the theme is the same. We exist in an utterly relational universe. Creation is ongoing as a dance without end. We, ourselves, are created over and over again as our bodily cells grow, mature, and die off, but not before giving life to countless new cells with new variations made possible through the myriad relationships and interactions that occur within our physical bodies and between our bodies and our external environments. No doubt similar processes are at work in the realms less observable, such as in the inner workings of our minds and hearts. Acknowledging this, all major spiritual traditions teach paths of transformation. If our minds and hearts are patterned like everything else in the knowable universe, they are always in the process of changing and evolving. We seek spiritual paths and, increasingly, science-based paths, to take a more active role in our personal evolution involving the growth and transformation of our hearts and minds.

I have prioritized this interest in my life from a very young age. I have learned from different spiritual paths as well as from the science of depth psychology, and more recently, neuropsychology, to help me navigate the journey toward a more whole and healthy life, characterized by a more authentic and loving relationship with myself and with others.

When I encountered Natural Lifemanship several years ago, I immediately recognized the opportunity to practice in practical, embodied ways many of the same processes at work in my spiritual journey. I’ve often reflected on how the principle of pressure has worked in my life to help me to grow more connected with self, with others, and with God. I’ve noticed the ways I’ve experienced pressure, at first as a kind of gentle nudging in my heart toward some kind of change process not fully understood. On some level, I feel I am asked to trust and cooperate with a process, although I may have no idea where it is leading. At the early stages I can’t quite put words to what is being asked of me or know how to respond, but the sense of pressure persists, gently increasing until I can’t ignore it anymore. At this point I start actively seeking an answer, which is Natural Lifemanship’s definition of resistance – not an undesirable thing, rather a positive search for an answer in response to pressure. In fact, my life’s most important lessons and periods of growth came about through the process of acknowledging some internally felt pressure, struggling with it, and finally cooperating, allowing it to change me in ways I never could have foreseen and never would have experienced without my willingness to trust, listen and observe, and cooperate, often blindly, with what I sense is being asked of me.

Another way NL has given concrete language to a pattern I’ve experienced in my deeply personal relationship with God is through the notion that the relationship grows through both attachment and detachment. Attachment in our spiritual lives refers to those wonderful life episodes and experiences where we acutely sense the presence of God, or a higher power, or a deeply felt connection with something greater, in our lives. This is usually felt as a consoling, meaningful, hopeful, warm and embracing presence utterly nurturing and sustaining us. It gives us the sense that all is well and that we can endure whatever struggles we may be experiencing.

The writers of the Judeo-Christian bible and many other religious texts all describe this sort of relationship, where faith is built through such affirming experiences. The early stages of faith can be described as a connection being built through attachment, or what is felt as presence, or the responsiveness of the subject of faith. This is even spoken of in Buddhism, a spiritual path generally unconcerned with the question of an ontological God, but essentially concerned with one’s epistemological relationship with What Is, with reality. Reality is what it is but our lens or our way of seeing and perceiving reality may be clear or it may be clouded. In the case of Buddhism, the lens of perception is polished through practice, but human nature is such that humans won’t persist at practice without some sense of reward. So it is said even in some forms of Buddhism that faith grows at the early stages as the pattern of the universe, being inclined toward evolution, reinforces a sincere practitioner’s efforts in faith (causes) by producing tangible effects experienced as answers to prayers.

There comes a time, however, when faith is tested. There are periods of our lives for many of us in which we feel disconnected from the faith that has sustained us. We experience no sensation whatsoever of the presence of God. Our vivid, Technicolor faith lives seem to have become monochrome and dull. To the extent that we have felt a deep connection before, we may feel utterly abandoned. We may cry, as many of the psalmists and even as Jesus did, “my God, why have you left me?” John of the Cross poetically described this dimension of our spiritual lives as “the dark night of the soul.” As a spiritual director, he did not wish the dark night on anyone but listened for it in those he counseled. Not everyone will experience a dark night, for there are those who may never cease to find consolation when they seek it in their daily lives and normal activities of faith. John maintained that one shouldn’t give up these routines or activities so long as they are producing satisfying results. This is a blessing in and of itself.

Some, though, are invited into a deeper intimacy with God through a fundamental testing of our faith. John of the Cross describes it this way (paraphrased): Our hearts were made for intimacy with the One who created us, and nothing less than a connection directly with our Source will satisfy us at the deepest level of our soul. And yet in our lives, we easily become attached to the more surface consolations available to us and we may rest our identity in something less than our truest selves – which is our true nature as children of God. God, therefore, weans us off of our reliance on consolations – or felt presence – by seeming to withdraw from us. The dark night can, therefore, be understood in NL terms as God, or our relationship with the Divine (however we know the Divine), practicing connection with detachment with us.

The goal is that we begin to cultivate a secure attachment, or enduring sense of connection – one we readily turn to regardless of whether we perceive God as being with us, or not. In Christian theology, God enacted the same pattern by being with humanity (through Jesus’ human presence) to withdrawing from humanity (Jesus’ death) to presence again (appearances after the resurrection) to withdrawal (Pentecost) but at the same time gracing humanity with the presence of the Holy Spirit, also known as “the comforter” or consoler. This pattern of attachment and detachment to build secure attachment (connection) in relationship is written into the gospel, itself.

My hope for all who read this is that in those moments of despair or loneliness and isolation, you find peace knowing that your Source of comfort and of life itself may not always seem near but it is always within. Know that perhaps you are being invited to discover and to rediscover an even more enduring sense of connection in the depths of your lives, one that doesn’t rely on any evidence of response (such as answered prayers) or a felt sense of presence. May we all develop a deep connection with self and the indwelling Spirit that is attuned to the still small voice within. The reward of such a sense of connection is the relationship itself – a “secure attachment” both earned and given by grace.

Recent Comments