…Why Do We Ride Horses

In Natural Lifemanship, mounted work is an integral part of our model of trauma-focused equine assisted psychotherapy (TF-EAP). However, I recently read a published article arguing that horseback riding is contraindicated in the treatment of military veterans with moral injury. The authors suggest that mounted work victimizes the horse and puts the client in a place of power, domination, and control. While we do not disagree that relationships characterized by power, domination, and control are indeed contraindicated for this population and for others, we feel this article begs two important questions with respect to equine assisted psychotherapy: 1) what benefits are accrued uniquely through mounted work that renders it an integral component of TF-EAP; and 2) is the aforementioned power dynamic an inevitable byproduct of riding, or is there a way to engage in mounted work that promotes its benefits without resulting in a damaging relational dynamic? Natural Lifemanship strongly contends that riding has powerful therapeutic benefits that cannot be obtained by other means and is contraindicated only when it is not done in a connecting and mutually beneficial way. Let’s explore why this matters – therapeutically speaking.

The physical benefits of horseback riding are well documented in the literature. Due to the many physical benefits, specifically related to balance, gait, and psychomotor difficulties, there have been many efforts to produce a horseback riding simulator for the purposes of physical rehabilitation and training. A company in Japan claimed, “almost 100% reproducibility (of the horse’s movement) has been achieved.” The simulator is not able to walk, but it does synchronize the six major movements of the horse while under saddle. However, in a publication about this simulator, the authors note that it does not have a mechanism “which catches the center of gravity movement of the rider.” They go on to explain that this important aspect of carrying is “similar to the case where the mother who is carrying her baby on her back is able to keep her balance compensating for the baby’s movement.” The simulator can reproduce movement, but it cannot reproduce the responsiveness of a sentient being carrying another. The ability of the horse to respond to the rider’s body and balance, much like a mother carrying her child, is more than just convenient. This responsiveness between the carrier and the one being carried activates physical attunement and connection in the relationship – the horse adjusts to the rider, and eventually, the rider adjusts to the horse. Movement alone organizes the lower regions of brainstem and diencephalon, but movement with attunement to the other and responsiveness is the relational connection, which reaches higher in the brain, targeting the limbic system. So while the movement of a horse can be reproduced, even the scientists responsible admit that there are limitations to riding a non-responsive machine. This is merely the beginning of what makes riding such an important part of treatment for mental health disorders.

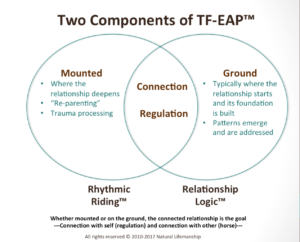

In Natural Lifemanship there are two major components of TF-EAP – Relationship Logic and Rhythmic Riding. Relationship Logic takes place on the ground and Rhythmic Riding takes place on the horse’s back. Whether mounted or on the ground the connected relationship is the goal. This is the most important aspect of why riding a living, breathing horse is more valuable than using a tool – connection between horse and rider can make all the difference.

In Natural Lifemanship there are two major components of TF-EAP – Relationship Logic and Rhythmic Riding. Relationship Logic takes place on the ground and Rhythmic Riding takes place on the horse’s back. Whether mounted or on the ground the connected relationship is the goal. This is the most important aspect of why riding a living, breathing horse is more valuable than using a tool – connection between horse and rider can make all the difference.

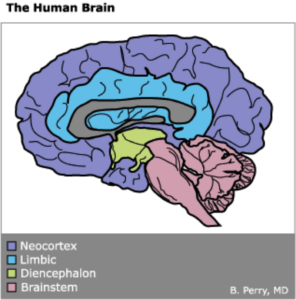

So why does connection matter so much? The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT), developed by Dr. Bruce Perry, is one of the primary problem-solving approaches that guide the sequence and progression of treatment in TF-EAP, for example, when and in what way mounted work is used.

Dr. Perry divides the brain into four main regions:

1. Brainstem

2. Diencephalon

3. Limbic System

4. Neocortex

We do realize that this is an oversimplification of very complex neurological systems. Nonetheless, we have found that simplification makes this information more accessible in clinical practice.

In Trauma-Focused Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, our primary goal is to integrate these 4 major regions of the brain so that the different regions can communicate effectively. For health and well-being, it is necessary for them to do so because they are responsible for all the major functions that support us. The brainstem is responsible for automatic systems like breathing and heart rate, as well as our survival responses of fight/flight/freeze. The diencephalon directs our movement and motor skills. The limbic system is responsible for connection, bonding, and emotional experience. And finally, the uppermost region, the neocortex is responsible for our abstract and concrete thought. Imagine if any of these major regions were to be significantly hindered – leading a typical life would be quite difficult.

Why does an integrated brain, one that communicates easily across regions, matter in everyday life? Ultimately, it makes self-regulation, and therefore self-control, possible – the neocortex is able to guide the entire brain and when necessary override impulses for fight, flight, or freeze in the lower regions. When the neocortex is integrated with the rest of the brain, we can think before we act. For this to happen there have to be actual neuronal connections (think of roads in our brain) going from the lower regions of the brain up into the neocortex. This can only happen when all 4 regions have gotten that rhythmic, predictable input that helps them grow and operate in an organized fashion. The limbic system is in charge of connection…bonding, attachment, and therefore key in having healthy relationships. It is also crucial to understand that the limbic system is nested between the upper region of the neocortex and the lower regions of the diencephalon and brainstem. Without an organized and functioning limbic system – not only does one’s ability to connect falter, but the rest of the systems do as well. The disorganized limbic system interferes with all other cross-brain communication.

Additionally, an integrated brain with adequate cross-brain connections or pathways (making it possible for the entire brain to work together) results in a secure attachment pattern. Children and adults with a secure attachment pattern are able to feel connected and secure in their intimate relationships, while still allowing themselves and their partner to move freely. Numerous longitudinal studies have shown that infants and toddlers with a secure attachment to a primary caregiver do better during adolescence and adulthood in a variety of areas related to self-regulation, and relationship with self and others. With this foundation in place, they are more resilient when traumatic events occur. For example, research has shown that securely attached individuals in the military report far fewer incidences of PTSD symptoms. For those who didn’t develop a secure attachment in childhood, intentional therapies like Rhythmic Riding can form the cross-brain connections necessary for brain integration, what people in the attachment field call an “earned secure attachment.”

Lastly, an integrated brain can better process traumatic events and memories. Be on the lookout for a blog explaining how and why we use mounted work to process trauma through the use of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

While brain development, integration, and attachment all begin in utero, I would like to focus on what happens after birth to continue this process. In reference to the primary caregiver, I am going to use the terms “Mommy, Mama, or Mother”, primarily because my experience as a primary caregiver is as a mother. Also, I will utilize some pictures throughout the remainder of this blog for two reasons:

1. To illustrate some core concepts, and

2. As an excuse to show you some pictures of our adorable child! ☺

Okay, so something like this scenario represents the ideal situation: When a baby cries, the mother picks up the baby and starts to rock or bounce him, while talking with a soothing tone and cadence, or maybe singing. All the while the rhythmic heart rate of the calm and regulated mother is regulating the heart rate of the baby. The electromagnetic field of the heart, the rocking, and the calm, rhythmic sounds of the mother’s voice passively activate the brainstem and the more this rocking, singing, and talking occurs the more the brainstem continues to develop in an organized manner. Passive movement causes an active movement that happens even more as the baby grows and begins to manage some of his own balance when being held and rocked. This develops and organizes the diencephalon. When a child is upset in some way the mother feels a deep connection to her baby. Oxytocin is coursing through her body as her limbic system is activated and she is overcome with love for her child. As the brainstem and diencephalon develop and organize it makes it possible for the child to connect to the one holding him, and the limbic system of the child begins to further develop and organize. This occurs most remarkably, between 18-24 months, the sensitive period for attachment learning.

Each time the child is rocked, carried, touched, and moved in a rhythmic manner while also experiencing love and connection, pathways throughout the lower regions of the brain are formed – the beginning of integration. When these parts of the brain are integrated, it creates the ideal environment for the neocortex to optimally develop. The baby starts to explore and learn from his environment, and thus begins the development of concrete and abstract thought. The activation and organization of the limbic system is the crux of an integrated brain because it touches every part of the brain. For example, if the mother is disconnected, depressed, or struggling with something that makes it difficult for her to emotionally connect with her baby, the lower regions of the brain may develop through rocking, but limbic system development will be compromised. When the limbic system is shut down or disorganized, it is like a roadblock from the lower regions of the brain to the thinking part of the brain (neocortex). Remember, in an integrated brain the neocortex guides (and sometimes overrides) what is happening in the lower regions of the brain. Basically, connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks me sets the foundation for an integrated brain and secure attachment.

This is a Mommy. She can simultaneously provide rhythmic, regulating movement AND connection.

This child (who is quite adorable, indeed!) is connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks him.

It’s worth noting that this was a tough night and I had to work the next day! Just sayin’

This is a Daddy. Just to be fair, he too, can simultaneously provide rhythmic, regulating movement AND connection.

Please disregard the “do NOT take a picture of me!” look. (It’s somewhat genetic! ☺)

This was taken after a full day of Christmas shopping – thank goodness there was a rocker at Toys ‘R’ Us!

Many children (and, therefore, adults) do not get what is needed for their brains to integrate. Both sensory input and connection are needed for optimal brain development. When this input is unpredictable and arrhythmic the brain will be disorganized. When it is lacking, like in cases of neglect, development and organization are compromised. Additionally, trauma that occurs later in life, like military combat, can compromise integration. When we live in a situation for a period of time in which the survival centers are hyper-activated and the limbic system is hypo-activated, our brain changes, much like a muscle can, to accommodate the manner in which it is being used. In the trauma world, we understand the importance of somatosensory and sensorimotor input for organizing the developing brain and re-organizing the traumatized brain. In fact, numerous sensory tools are used for just this purpose – I have quite a few of them in my offi ce. Understanding how to best utilize these tools is an important part of trauma informed care, but this is not the focus of our conversation today. Many of these tools (pictured to the left) help to organize and regulate the brainstem with passive sensory input. However, they do not move our body or require that we move our body. They do not have the ability to form a relationship or connection with us. They can, though, work wonders for the dysregulated brainstem alone.

ce. Understanding how to best utilize these tools is an important part of trauma informed care, but this is not the focus of our conversation today. Many of these tools (pictured to the left) help to organize and regulate the brainstem with passive sensory input. However, they do not move our body or require that we move our body. They do not have the ability to form a relationship or connection with us. They can, though, work wonders for the dysregulated brainstem alone.

Another of my favorite tools is the rocking chair or glider. I think every therapist should have one of some sort in their office and every equine therapy program should have them in the barn and next to the spaces in which they meet with clients and horses. Rocking chairs pr ovide rhythmic, patterned, repetitive movement that is passive (activating and organizing the brainstem). In order to maintain posture and balance in the rocking chair, the muscles contract which is an active movement. Passive movement thereby causes active movement, which moves us up a bit higher into the brain – the diencephalon. The rocking chair is not, however, alive. It does not have a limbic system or the ability to connect, bond, or love another. Brainstem? Check! Diencephalon? Check! Yet, still no connection.

ovide rhythmic, patterned, repetitive movement that is passive (activating and organizing the brainstem). In order to maintain posture and balance in the rocking chair, the muscles contract which is an active movement. Passive movement thereby causes active movement, which moves us up a bit higher into the brain – the diencephalon. The rocking chair is not, however, alive. It does not have a limbic system or the ability to connect, bond, or love another. Brainstem? Check! Diencephalon? Check! Yet, still no connection.

This rocking horse cost about $40 (a bit inflated, because it’s “vintage”). There has been absolutely no upkeep or cost since the day I purchased it!

It offers rhythmic, regulating input, and earned its keep in Cooper’s one-year pictures, but still. . . it is not alive. No connection. You get what you pay for!

This is where horseback riding distinguishes itself. Being on the back of a horse can calm the nervous system through the movement that is inherently rhythmic, patterned, and repetitive. When a person is sitting on a horse, they do not have to create the rhythm or the movement, so the brainstem is passively regulated. Additionally, the sound of the horse’s feet and the movement that can be seen (like the movement of the horse’s head) all passively regulate the brainstem. As the horse moves, the rider’s muscles actively contract to maintain balance so the diencephalon is able to regulate. This is really great, but isn’t this something that could just be done with a rocking chair? It could definitely be argued that the movement of the horse is much more complex than that of a rocking chair. The physical and psychological benefits of this movement are so great that much effort has been made to re-create this complex movement. Yet, even if a simulator is able to fully reproduce this movement, the simulator still lacks the ability to activate and organize the limbic system, something we believe a live horse is definitely capable of …if we allow the horse to be more than just a “sensory tool.”

So, how do we ride horses in a way that fosters rhythmic limbic input? When the horse and rider are able to form a relationship based on attunement and connection, the limbic system is activated and organized. But, a paramount distinction is this kind of relationship is not possible when we operate from a paradigm of power, control, and domination. Pause for a moment and consider how often humans utilize power and control with horses – even if done gently. When the horse is encouraged, even through kind or humane techniques, to appease, submit, or dissociate, the horse becomes no more than a rocking chair or a horseback-riding simulator. When connected to the rider, the horse can help the rider to connect (engaging the limbic system), just like the mother who connects to the baby. The rider’s brainstem is passively regulated as the horse moves. The diencephalon is regulated, as the passive movement becomes active movement. The limbic system is activated and organized when the rider and horse connect and begin to respond one to another. Again, connecting to and bonding with the one who carries and rocks me is how an integrated brain develops and a secure attachment is formed. If we are going to simply use the horse as a “sensory tool”, we might as well use actual sensory tools, rocking chairs, or the horseback riding simulator – all of which are much cheaper, require significantly less maintenance and carry less liability. The horse’s ability to connect is where the real healing happens, and it is what differentiates her from the many other sensory tools to which we have access.

Many would argue that if connection is ultimately the goal – why couldn’t therapists simply work with smaller animals like dogs? It is a legitimate question. However – while connection is absolutely necessary for the rest of the integration to occur, most clients who have experienced trauma need the passive regulation and motor stimulation of riding, which offers the sense of being carried AND connected with, all at once.

Lots of connection here! However, generally speaking, riding of the dogs and chickens is frowned upon in our home.

Really, no matter our age, sometimes we just need to be rocked and deeply heard in a connected relationship. I’ve watched horses do this in ways that still bring tears to my eyes.

This is a horse (Peanut to be exact!). He, too, provides rhythmic, regulating input and movement. He is an alive, sentient being, and most definitely capable of connection! (He is not a rocking chair or sensory tool)

Arguably, the fact that the horse can carry us, rock us, and connect with us makes her different than any other sensory tool and most other animals. With this comes quite the responsibility, however! The mental health and equine professional must learn how to tell the difference between compliance, appeasement, submission and. . . connection. Between dissociation and cooperation. We must continue to learn what connection looks and feels like as we relate to humans and horses, which typically requires that we understand ourselves, and that our intimate relationships are characterized by genuine connection. NOT an easy thing to do, but we believe it is necessary to really, intentionally help our clients reorganize their brains, learn new, healthy ways of connecting, and ultimately, heal.

Let us return to the article I mentioned in the beginning. In this recent publication about why horseback riding is contraindicated for the psychological treatment of military veterans who have suffered moral injury, the authors do a beautiful job of describing the difference between psychotherapy and recreational activities. There is also wonderful information to help the reader distinguish between PTSD and moral injury. I very much appreciate the authors’ understanding of trauma and the insistence that clinicians need extensive training in a number of modalities to ethically work with this high-risk population. The authors also make it clear that horseback riding is not psychotherapy. In NL we definitely do not believe that horseback riding, in and of itself, is psychotherapy. On the majority, I agree with the distinctions made in this article.

However, the authors described riding in a way that, I must admit, made me cringe. There was talk about cross-ties which greatly restrict the horse’s movement and choice. The authors described saddles “made of dead animal hide,” and cinching up the horse in a way that compresses the two areas of the body that are the most vulnerable to attack by a predator. The description was quite graphic. The authors then, correctly in my opinion, conclude with the following statement: “We have rendered a horse docile and submissive and put a warrior in a position of control and dominance. We have established a predator/prey relationship. And for a war veteran, we have evoked the experience of being a perpetrator in control of a victim. Within the context of this duality, morally injured military veterans, struggling with feelings of worthlessness, self-hatred and inner evil because of what they have done or witnessed in combat, are being obstructed from the deep healing of soul that they so desperately need.”

Yes, I agree 100% that if this is the only paradigm you have for riding a horse, then riding is, indeed, contraindicated not only for military veterans with moral injury, but for any person seeking psychotherapy services, especially those who have experienced relational trauma. I strongly support that the authors challenged the status quo. They shed light on one of the ways in which EAP can, indeed, be damaging to our clients. There is, however, an assumption made by the authors with which I do not agree. I do not agree that the way they described the horse’s and the client’s experience of mounted work is the only experience possible. Horseback riding is not the problem. The paradigm of power, domination, and control is the problem, and this is a problem in any clinical setting, and honestly, in most horse-human relationships in general.

If your only paradigm is one of power, control, and domination, it is best that you utilize many of the amazing sensory tools available to clinicians, and don’t partner your clients with horses. A paradigm of power, control, and domination is damaging and traumatizing (and often re-traumatizing) for both the horse and the client, even if the domination and control is done “gently”. This paradigm is also a problem when building a relationship with a horse on the ground – this is not just about riding. A partnership based on connection, attunement, trust, and mutual respect starts on the ground, and all that is built on the ground must transfer to the horse’s back if mounted work is going to be restorative and transformative for both the horse and person. Again, this often requires an enormous amount of learning, practice, and a willingness to let go of old beliefs and patterns. The most intimate we will ever be with a horse is on his back – the place we can experience much joy but also much risk and vulnerability. If power, control, and domination are our only options at the height of intimacy, it might be worth dismantling the principles we employ, both mounted and on the ground.

Therapeutically speaking, the ability of the horse to carry, rock, and connect is powerful for brain integration, which all humans need and is at the core of the work we do with most of our clients. While we do ride to reach other therapeutic goals, the primary reason we ride horses in therapy is because of the horse’s uncanny and unmatched ability to “re-parent” and restore that which was lost in an organic and powerful way. Riding, then, is only contraindicated when that riding is not done in a connecting and mutually beneficial way. When horses are allowed to do what they do best – connect, and sometimes carry, then riding can be an unparalleled therapeutic intervention for lasting change. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater – what is necessary to do good work with horses isn’t just ‘what’ we do, it is ‘how’ and ‘why’ we do it. That understanding is at the foundation of Natural Lifemanship, and it is why we can proudly say, “Yes, we DO ride in therapy!”

References:

Escolas, S.M., Arata-Maiers, R., Hildebrandt, E.J., Maiers, A.J., Mason, S.T., and Baker, M.T. (2012) “The impact of attachment style on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in postdeployed military members.” U.S. Army Medical Department Journal.

Kitagawa, T., Takeuchi, T., Shinomiya, Y., Ishida, K., Shuoyu, W., and Kimura, T. (2001) “Cause of Active Motor Function by Passive Movement.” J. Phys. Ther. Sci. Vol. 13, No. 2, 167-172.

Perry, B.D. and Szalavitz, M. (2006). The boy who was raised as a dog and other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook: What traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. New York: Basic Books.

Siegel, D. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. Bantam.

Siegel, D. (2012) Applications of the Adult Attachment Interview. PESI Publishing & Media

Usadi, E.J., & Levine, S.A. (2017) “Why We Don’t Ride: Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, Military Veterans, and Moral Injury.” Journal of Trauma and Treatment, 6 (2), 1-5

Recent Comments