by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Dec 8, 2021 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship

By Bettina Shultz-Jobe and Tim Jobe

On August 7th, 2010, Tim and I were married. We had a sunrise wedding at my family’s ranch in the Texas Panhandle. It was outside on a plateau, overlooking a beautiful canyon, so sunrise was about the only time of day we could lessen the chances of enduring ridiculously high and relentless winds––the kind that blows houses over the rainbow, twirls wedding veils into a wadded up mess, and wreaks havoc on a sundry of other wedding delights.

We did our first dance horseback to a country song called I Run to You, and I almost fell from Zeus, my trusted steed. We shared a communion of coffee and homemade biscuits with friends and family during the ceremony. We then had tequila sunrises and a delicious chuck wagon breakfast, prepared by a dear friend. The day was perfect!

It is practically impossible to think about our wedding and engagement, without thinking about our business, our first “baby.” The weeks prior to our wedding we built a website, (with the help of my brother in law), trained our horse, Aries, for the aforementioned wedding dance, set up an LLC, and. . . oh yes––planned a wedding! We simply can’t separate ourselves or our relationship from Natural Lifemanship and the idealized belief system at its foundations.

Many years ago, Tim and I wrote the statement you will read below. Natural Lifemanship has grown well beyond the two of us, but these beliefs are the hands that continue to hold us personally and professionally. They are still the touchstone of Natural Lifemanship’s principle-based and process-oriented approach to therapy and learning.

Moments after we were officially married the wind arrived––and, truly, it has been a whirlwind ever since!

We are terribly imperfect at practicing what we believe and what we teach. I guess this is why we so deeply believe in the power of grace and repair. Tim and I are quite complicated human beings, with all kinds of baggage, and a fly on the wall would attest to how inadequate our best is in the hardest of times. Actually, our closest family and friends can attest to this wholeheartedly, I’m sure.

We are so very different from each other, and there is a rub that doesn’t work each and every moment but does seem to work out most days. So much has changed for us in the last 11 years, but what we believe has not, and our daily choice to try our darndest to care more about connected relationships than anything else remains.

The statement below is found in The Natural Lifemanship Manual, which is intended to serve as a resource to support students’ learning as they move through our Fundamentals and Intensive trainings. It is also what our certification students agree to before they complete certification in Natural Lifemanship.

As Tim and I reflect on how these beliefs have affected our life, our mission, and our passion, we feel infinitely blessed to be part of a community that chooses to attest to such a statement––and humbled by the many people whose work and heart have contributed to our mission––and by each moment’s grace to change, grow, and, above all, connect.

NL Ethics and Beliefs Statement

Committing to weeks, months, or years of learning with a specific teaching organization is also the forming of a new relationship. It is our hope that you do so with a clear understanding of who we are and why we do what we do. Whether you intend to become certified, or are just trying out a training, it is important to us that we “orient” you to The Natural Lifemanship Institute so we begin on a foundation of trust. We want to be in good relationship with you! With that in mind, we have written an NL Ethics and Beliefs Statement that we feel answers the ‘who we are’ and ‘what we do’ question from an existential and ethical standpoint. This is the big picture of Natural Lifemanship and it is a commitment embraced by our certified practitioners. It is our goal that students learning with us will come to understand and integrate these ethics into their own way of being in the world. This statement is included in this manual so that you may know who we are and what we stand for.

As a person certified in Natural Lifemanship I attest to the following:

I believe the most important thing in life is connected, attuned relationships with self, others and the world around me (including relationship with animals, my Creator as I understand him or her, and nature, the universe, etc.) All of life’s healing happens in the context of attuned relationships based on trust, mutual respect, appropriate intimacy, and partnership.

I believe strength is found in vulnerability, and that conflict in relationships can be an opportunity for growth that can strengthen the relationship. Therefore, regardless of the task or activity, a connected relationship with self and others is always the goal.

I believe that a partnership can happen when each party seeks to control or manage themselves only, and true partnership happens when each party appropriately manages themselves for the good of the relationship. I believe that if it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either and that a one-sided relationship is damaging to both parties.

Regardless of what is going on around me, it is possible to control what is happening inside of me. Relationship with self (what we sometimes call self-regulation or my way of being in the world), quite simply, flows out of relationship with others, because effective self-regulation is born out of safe co-regulation. Relationships are then built on the foundation of relationship with self.

Therefore, WHO I am is more important than WHAT I do. I realize that I can’t teach someone to do something I can’t do. Likewise, I can’t teach someone to live a life that I don’t live. As a result, personal growth becomes the foundation for ethical practice.

The most important thing is to do my best to do what is right for my client. I understand that what is best may not be what is easiest. In order to do what is right for my clients, I have to know myself – my biases, my blind spots, and at the moment, I have to be connected with my own reactions and impulses so I can filter them. Only then can I do what is actually, truly best for my client.

The team approach in NL affords me the opportunity to model a relationship where the NL principles play out and provides a space for the therapy or learning team to notice and discuss biases and blind spots. It is, therefore, my ethical obligation to foster a healthy relationship with my therapy partner. Clinical consultation is a regular part of ethical practice, especially if I am, at times, working alone in therapy sessions.

I believe animals are sentient beings, who have relational and thinking capabilities, and can be capable of partnership if given the chance to develop.

I believe that a good principle is a good principle regardless of where it is applied. Therefore, all NL principles apply equally to relationship with self and others. The relationship between horse and human is a real relationship in which relational patterns emerge, just like in any other relationship. All NL principles apply to this relationship as well.

When NL certified, I become part of a community of individuals who are deeply committed to connection with self and others, and who strive for connected relationships the way nature intended. As such, this community of practitioners strives to foster relationships that bring about healing for self, others, and the animal partners with which we work.

________________________________________________________________

We invite you to join our growing NL community where transformation, healing, and purposeful relationships take place. Learning how to best serve your clients and communities is a lifelong and deeply fulfilling journey – we would be honored to join with you on this path.

Registration for the next Fundamentals of Natural Lifemanship training opens in September! This is our most entry level training and is required for all certification paths. We hope you can join us!

by Sarah Willeman | Dec 6, 2021 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship

By Sarah Willeman Doran

“Being human is about being in the right kinds of relationships,” said John A. Powell, author and civil rights scholar. He was speaking about social justice and the central importance of living from our heartfelt connection with other beings. At the most basic level, feeling genuine care helps us get along with each other. And from a larger perspective, the felt sense of connection—with ourselves, with others, with animals, with nature, with our conception of spirituality or the divine—is what brings meaning to our lives. At the end of life, when we look back, achievements and material things will matter much less than the quality of our relationships, our lived experiences of love and care.

In fact, the quality of our relationships affects not just our sense of meaning but also our psychological and physiological health. As the well-established field of Attachment Theory teaches, we need to form safe, caring bonds with other beings in order to have healthy nervous systems. Secure attachment creates neural pathways that are crucial for the functioning of our brains. In other words, our biology is intertwined with the natural yearnings of our heart. As mammals, we are born with an innate desire to connect. We yearn for experiences of trust and mutual understanding. Connected relationships are central to our wellbeing.

Natural Lifemanship: A Model for Building Connection

The field of trauma therapy offers insights that can help all of us heal and thrive. Trauma is notoriously difficult to treat, because it lives not only in our conscious mind but deeper in our nervous system, in parts of the brain responsible for basic survival. We can’t will our way—or talk our way—out of it. Instead, we need to understand and heal the functioning of the nervous system. Horse-assisted therapies can help people regulate those deep, surivival-focused brain regions and reintegrate the relational parts of the brain. Much of trauma happens in relationship, and trauma can most powerfully be healed in genuine, connected relationship with another.

Natural Lifemanship is a model of equine-assisted learning and psychotherapy that fosters healing through connected relationships. The model combines neurobiology with sound relationship principles. Clients learn the principles by working with horses and then can translate those principles to all other relationships in their lives. Natural Lifemanship heals and integrates the brain, develops self-awareness and self-regulation, and empowers people to build the kinds of connected relationships we all need.

I came to Natural Lifemanship from a background of psychology, horsemanship, and my own trauma history. As a rising young star, I lost my showjumping career to traumatic injuries. Although I never returned to the big sport, I fought my way back to being able to ride and work with horses again. In recent years I’ve raised and developed young horses. Natural Lifemanship has helped me to work with horses who’ve had difficult experiences. It has also helped me to heal myself, strengthen my relationships, and build transformative new ones.

Beyond just therapy, Natural Lifemanship is a way of living—a guiding mindset for how we relate to people, animals, ourselves, and the world around us.

The Neurobiology of Survival

The brain of a horse works similarly to the brain of a traumatized person: the lower, survival-focused brain regions are largely running the show. Horses’ brains are naturally built this way. Compared to humans, horses have a small neocortex, the region responsible for thinking. In herd life, only the lead mare needs to do much thinking. Horses are prey animals. They mainly need their fight-or-flight reflexes, and they need to follow the herd. Survival is the horse’s essential skill, and it’s governed by the lower brain.

With trauma, a person becomes stuck in those same lower brain regions. The fight-or-flight response actually has a third component: it’s fight, flight or freeze. When a person is stuck in these states, the survival regions of the brain get over-exercised, the nervous system becomes dysregulated, and the person has trouble regaining internal calm.

That over-exercising of the lower brain leads to two things, anatomically: it builds up the lower brain regions and simultaneously sacrifices connections to the upper brain regions, where thinking and emotional connection happen. There’s a use-it-or-lose-it phenomenon with brain pathways. A traumatized person has trouble with self-regulation because many of the cross-brain connections that allow us to consciously calm our survival reflexes have been lost—or in the case of childhood trauma, perhaps never created.

These primitive lower brain regions may help us survive in life-threatening situations, but they do not serve us well in most day-to-day experiences of modern life. When we’re stuck in survival mode long-term, it wreaks havoc on our health, happiness, and relationships.

From Surviving to Thriving

The good news is the brain has plasticity, and new connections can form. The most effective trauma therapy first regulates the lower brain and then engages the upper brain regions, thereby forming new pathways, helping all parts of the brain to integrate with each other for healthy functioning. The survival-focused brainstem needs to settle before higher brain regions like the limbic system and neocortex can be engaged in relationship-building activities. Therefore, understanding the brain is a crucial part of helping people heal. It can also make all the difference in communicating with others in our daily lives.

Natural Lifemanship 101: We need to understand which part of the brain a horse or person is responding or reacting from. Responding is associated with calm, integrated thinking, while reacting is habitual and reflexive. This understanding is important because if someone’s in survival mode and we try to reason with their thinking brain, they’re simply not there to receive what we say. A child having a meltdown won’t respond to reason and logic because they can’t. You can’t talk someone out of a panic attack. A scared horse cannot learn.

The Natural Lifemanship model offers specific tools to help regulate the lower brain regions. Certain types of sensory input and movement—namely, rhythmic and repetitive—have been found to soothe the nervous system. Think of a steady heartbeat, rocking a baby, taking a walk, watching snow fall, or listening to ocean waves. We can learn to use these regulating tools for ourselves, and we can offer them, in appropriate contexts, to help others settle.

First and foremost, to connect with others we need to become aware of our own internal state. Horses instinctively sense our physiology and give us direct and honest feedback: if we’re dysregulated, we won’t feel like a safe person for the horse to connect with. Do the same outward gestures with a different internal state, and you’ll get a completely different response from the horse. Similarly, humans respond to these biological signals without even realizing it. When people react to us in ways we didn’t expect, the state of our nervous system can sometimes play a role.

On the positive side, when we develop self-awareness and self-regulation, we have a reassuring effect on those around us. This is partly because we feel the electromagnetic signals from each other’s hearts. When our heart is rhythmic and regulated—in a state called coherence that corresponds with a regulated brain—we broadcast calm and safety. To form healthy relationships, we need to be able to access this state. And the feeling of connection, in turn, helps us regulate; the cycle reinforces itself in a deeply healing way.

In the Natural Lifemanship model of therapy and learning, the client gradually builds a healthy, connected relationship with the horse by learning to self-regulate, make requests of the horse, recognize the horse’s signals, and respond appropriately. The horse is seen not a tool or a metaphor but as what he actually is: a real, living being with whom we can form a real relationship. Communication with a horse is visceral and genuine. When it goes well, there is simple, genuine pleasure. Connection is inherently rewarding for both human and horse.

In this work, the principles learned while working with the horse apply to all other relationships, with both humans and animals. These sound relationship principles hold true across all contexts. Once we’ve internalized them, they can provide us with a source of inner guidance to help us navigate whatever situations arise.

Natural Lifemanship 101: A good principle is a good principle no matter where it is applied. In other words, whether the context is therapy, learning, horsemanship, parenting, marriage, or team building at work, the guiding ideas are the same. For example, self-awareness and self-regulation are crucial to the health of every relationship. And as you read each new principle introduced in this article, you might pause to consider how it applies to relationships you’ve experienced—and how it might offer guidance for navigating any challenges in your life.

Nabo’s Story

The story of one horse in my care illustrates the transformative power of connection. I worked with him over the course of several months and saw his wellbeing and pattern of relating to humans completely change for the better. The principles of Natural Lifemanship guided my approach, in a way that went far beyond any traditional horsemanship training.

His name was Nabo. He was a shiny auburn bay with fine graceful limbs and a big, expressive eye. He arrived at my barn fearful about riding. At the previous barn, they said he had too much blood—too sensitive, too fast, too hard to slow down. It seemed to me they’d trained him with controlling methods, thereby pushing him into survival mode. When I led him to the mounting block, he’d tense his body and widen his eyes in alarm. The bottom line was, if he didn’t feel safe and at ease, I wasn’t going to get on his back against his will. We needed to start over.

Natural Lifemanship 101: If it’s not good for both, it’s eventually not good for either. Any relationship that involves control, manipulation, advantage-taking, or one-sidedness is not a healthy relationship. When one party’s needs and wishes are continually sacrificed, both parties lose in the end. If we harm others or allow ourselves to be harmed, we do not thrive. A relationship on those terms cannot succeed.

In healthy relationships, we choose to do what’s right for the relationship, and we ask the other to do the same. Compromises can happen, certainly. But on the whole, we honor the needs on both sides.

Nabo needed a new kind of relationship with humans—one in which his needs and preferences mattered and there was mutual trust. It was time to do the work of repair.

Every day, I’d take him to the round pen and let him loose—no halter, nothing on his body except wraps to protect his legs. Using my body energy, gestures, and voice, I began to communicate with him. By sending energy toward him in different ways, I asked him to follow me, or stand quietly with me, or move calmly around the edge while we stayed mutually attuned. In this setting, he didn’t feel controlled in any way. I was simply making requests, and he could choose how to respond. When he began to understand and choose to cooperate, it felt good to both of us. This was the beginning of connection. And his sense of freedom and choice was central to the process.

Natural Lifemanship 101: You don’t want to take away the other’s sense of choice. When you come across too forcefully, the other doesn’t feel safe. They might comply with you because they feel they have to, but that’s not healthy. Compliance is a submissive action; it’s reflexive and robotic, arising from the lower brain’s survival instinct. What you want instead is cooperation, which is willing and freely chosen, arising from a whole-brain process in which the other calmly figures out what to do. In other words, control is not connection; willing cooperation is.

Importantly, giving someone choice means they might not always do exactly what we want. And we need to understand that’s part of relationship-building. It doesn’t mean we give up on our request; usually it just means we keep working on it in a healthy way. This is what’s needed if we want to build a good relationship.

A crucial thing in my work with Nabo was that I needed to make sure not to get offended by any of the “wrong” answers he tried. If I made a request and he reacted in a way I didn’t want, that was okay; he was just trying to figure things out. I simply needed to maintain my own regulation and keep asking—and wait until he started to get it. Once he tried a “right” answer, I’d immediately release the pressure, telling him, Yes, that’s it! Releasing the pressure, in other words, means I’d stop making my request—in this case, usually by taking a step back, so that I was no longer gesturing or sending energy in his direction. It’s essential to release the pressure as soon as cooperation happens, because that’s how the other knows they’re doing the right thing.

Natural Lifemanship 101: Release the pressure when the other cooperates. This is crucial. Releasing the pressure lets the other feel that they’ve done the right thing. And conversely, think of how unpleasant it feels when you do the right thing and someone keeps nagging, holds a grudge over a misunderstanding, or doesn’t forgive a mistake. That makes for a bad relationship. As an everyday example, if you’ve asked your teenager repeatedly to take out the trash and they finally do it, just say thank you. If you continue to pester them because you’re upset it took too long, that doesn’t help. You can work on improving communication in the future, but for now, give them a break and appreciate that they chose to cooperate.

Similarly, with Nabo, I needed to be patient and reward every attempt at cooperation. He was mostly in his survival brain, and it would take some time to change that pattern.

At first, Nabo was flighty. He’d hear a car in the driveway and take off across the pen, high-headed, almost frantic. In these moments I knew he’d lost his awareness of me. He’d run away from the noise and then back toward it, wide-eyed, snorting, tail streaming. I had to make myself big and flap my arms, telling him, Hey, I’m here too, don’t run me over. I was asking him to respect my needs even though he was upset; as the NL principles teach, letting him do things that were harmful to me wouldn’t help the relationship either. Gradually, I’d ask him to settle down and bring his attention back to me. When he seemed regulated enough, I’d ask him to come stand with me. Finally he’d take a breath. His eye would soften. He’d nuzzle me with his muscular, whiskery lip.

One day I had him loose in the indoor arena, a larger space, and we heard a horse gallop across the stable yard. (It had obviously escaped from its humans). The sound triggered his sense of alarm, and he took off at a high-headed canter. But something was different this time. He kept glancing at me, checking in. I kept my energy quiet, trying to project a sense of calm. And then he seemed to make a decision. He slowed his pace, trotted over to me, and stopped. I hadn’t asked him to come to me yet, but he seemed to be asking: Could I stand with you and try to calm down? He seemed to realize he felt better that way. Connection felt good to both of us, and he had internalized that knowledge. He took a deep breath and stayed by me.

After that, he was different. When we were in the pen, he might spook at a noise, but he’d settle quickly. He was learning to self-regulate. The connection between us was helping him learn it. Soon we reached a point where he’d hardly spook at all. He wasn’t getting triggered anymore. We could maintain our connection while I asked him to follow me, stand still while I walked around him, or walk, trot, and canter around the pen, moving between the paces as I raised or lowered my body energy. We were so attuned all I had to do was shift my gaze from his barrel (where my leg would be if I were riding) to his haunches (which he knew meant I wanted him to follow me) and he’d immediately come to me.

It was a warm, companionable feeling, experienced deep in the core of my body. Out there in the sun and wind, with this powerful, delicate, shining horse, communicating with energy alone: my heart felt tender and alive. A sense of peace and trust resonated between us. This was the sweet spot, the ongoing goal of our work: this powerful felt sense of connection, the key to overcoming Nabo’s fears.

Natural Lifemanship 101: Regardless of the task or activity, connection is always the goal. Connection is what it’s all about, the basis for all successful relationships. In any setting, if we get too task-focused, we tend to become tense and disconnected from the relational parts of our brain, which can undermine our success. On the other hand, when we learn to stay in tune with how we’re relating to others, our relationships improve and we get better outcomes in whatever we’re doing.

With Nabo, the next step was to work through his fear about riding. Now that we had such a beautiful connection, we could begin to approach this challenge. My task was not simply to get on his back, but rather to maintain our connection and build trust around riding, so he could learn to feel comfortable. I would need to break the process down into pieces he could manage.

I knew the mounting block would be a trigger for him. First, I brought the block into our round pen so we could start to work through his fearful associations. When he saw it, he immediately tensed and lost our connection. He was back down in his survival brain. Gently, gradually, I asked him to reconnect with me—to settle and bring his thinking brain back online—and practice what he knew. I wasn’t trying to use the block to get onto his back. I simply wanted him to learn he could still feel safe and connected, even with the mounting block nearby.

He began to learn the mounting block wouldn’t lead to scary things. Still, in order not to overwhelm him, I removed the block from the pen and introduced the idea of riding in a different way. I’d ask him to follow me to the fence, then I’d stand on the bottom rail, pressing my hand on his back. If he tensed, I waited for him to relax and then stepped down—releasing the pressure, telling him, Yes, that’s right, you’re doing well. Throughout all this, he still got to choose. He was free to walk away from me; I used no force or tools of control. If he wasn’t comfortable, I wasn’t getting on. I asked him to work with me, to see if we could sort out his fears together. We had to trust each other. Only when he stayed relaxed would I step one rail higher or add weight to his back. In this way, we progressed to the point where I could climb on bareback while he remained completely at ease.

The connection we formed changed Nabo’s life. He was no longer traumatized and fearful. He could enjoy being with his human. He could express a need and find that it mattered. And he could learn to do the right thing for the relationship, too. His demeanor and behavior changed because his brain changed. As he learned a new way of relating, he built new neuropathways that allowed him to regulate and connect.

Connection in Everyday Life

A connected relationship is one in which both parties choose to do what’s right for the relationship, and those choices are made freely and willingly. To reach this level of attunement, both parties need to make requests and listen to each other. Connection is built; it doesn’t just magically happen. You can’t fake a true, deep, safe connection. It has to be real. When we experience genuine connection, we feel it viscerally. It’s an internal, felt sense: that warmth, presence, peace and attunement; the feeling of being fully alive and at home in the moment and with each other. That’s what Nabo and I both experienced as we built our relationship together; that feeling itself was a much greater reward than any carrots or sugar cubes I could have fed him. And I can still feel our connection now, when I think back on the memory.

Natural Lifemanship 101: In healthy relationships, the felt sense of connection remains whether the relationship partner is physically present or not. We can cultivate that internal felt sense so that it stays with us even across distance. When we’re truly healthy, we carry the feeling within us rather than depending on the constant reassurance of physical proximity.

Working in the round pen, many people and horses feel more secure when they’re next to each other. Often people find it hard to ask a horse to walk away and circle the edge of the pen. They might say they “feel bad” when asking the horse for physical space, as if they’re being cruel. Some horses react with discomfort as well. But in order to have strong relationships, we need our sense of connection to remain whether we’re near or far. We need to feel secure in our care for each other. Just the short distance of the round pen’s space builds this capacity. We can feel deeply connected even when we’re apart.

Connection across distance applies to many aspects of our daily lives. For example, in a healthy relationship, spouses need to feel connected with each other even when one is traveling. Children just starting school may feel fearful about separating from a parent—but ideally, children learn to carry the feeling of the bond within them, even when they’re away from parents during the day. My Natural Lifemanship colleague recently got a note from her three-year-old daughter that said, “I really miss you today. I’m gonna love you when I’m at school.” These words, to me, reflect a parent consciously working with her child to develop an internal sense of connection.

The idea of connection across distance also applies to grief. Death is, in a way, the ultimate distance. When we lose someone we love, touching into our internal felt sense of connection with that person can help us heal. We can learn to feel the tender warmth, the deepest comfort of our hearts, even when someone is gone. Grief is still enormously painful, but the feeling of connection inside us cannot be taken away. This is essentially what it means to carry someone in our hearts: the blessings of love they brought to our life are forever part of us.

Spirituality is another form of connection across distance. When we connect with the divine, with nature, with source energy—whichever has meaning to us—we are attuned with something greater than ourselves, an abstract presence we cannot see. This kind of connection is a capacity we can cultivate through practice. It’s also a feeling that can naturally arise when we gaze across the mountains, watch a brilliant sunset, or witness an act of kindness. Something great and beautiful touches our spirit in these moments. Instead of feeling separate and alone, we feel part of something larger. If we bring our awareness to that natural feeling, we can deepen our visceral sense of it—a memory in our body and heart of the power of connection.

All these forms of connection, near and far, afford opportunities for us to develop this internal, felt sense. When we experience deep connection in one relationship, our capacity to cultivate it in others grows.

Natural Lifemanship 101: The way you do anything is the way you do everything. Specifically, our relational patterns are consistent across contexts. When we step into the round pen with a horse, our relational patterns will play out. This also means that whatever we learn through building connection in one setting is what we need to learn. Noticing our own patterns is the first step.

And importantly, as we move through the process of building stronger, more connected relationships, there is another essential teaching we need to keep in mind: mistakes and repair are a crucial part of relationship-building. In other words, we need to give ourselves and others some grace. Despite our best intentions, we will make mistakes. And that’s okay. A relationship that can’t survive imperfection is not a healthy or worthwhile relationship. In fact, mistakes and repair can make our relationships stronger.

Natural Lifemanship 101: We need to trust in our ability to repair, rather than trying to be perfect. Fear of mistakes hinders our ability to relate and thrive. Instead, we need to know we’re safe to be human. Mistakes and repair are part of building strong relationships. Moments of small, accidental damage and disconnection can deepen our relationships when we respond in a certain way: by hearing each other’s needs and making amends. This is the essence of feeling seen and cared for. In this way, we learn to understand and nurture each other through the ever-changing experience of life.

Global Repair

Feeling connected brings out our natural empathy and kindness. In today’s world, we need this work more than ever. Modern society suffers from an epidemic of disconnection. We fight with each other and mistreat the planet. We lose ourselves in devices and cannot even be present in the moment. Many people feel isolated and afraid, living with chronic stress. We’re spending too much time in survival mode.

Connection is the antidote. The work of healing is not just for people with severe trauma; it’s for all of us. We can all benefit from deepening self-awareness and self-regulation. We can all learn to strengthen our relationships with self, others, and the natural world.

For a society living in disconnection, it’s difficult to feel our shared humanity or interdependence with nature. On the other hand, if we can cultivate our own ability to connect, the healing effect ripples outward through everyone in our life. We learn to treat each other with care when we feel genuine connection with each other’s humanness and vulnerability. We learn to treat the earth with respect when we experience the genuine healing power of connection with nature.

We are interconnected with all of life. To fully understand that truth, we need to know the warmth and aliveness of the internal felt sense of connection. We need to carry it with us, at the core of our way of being in the world.

You can see video of Sarah working with Nabo here:

Natural Lifemanship With Nabokov, Part 1

Natural Lifemanship With Nabokov, Part 2

An earlier version of this article originally appeared in the EcoTheo Review.

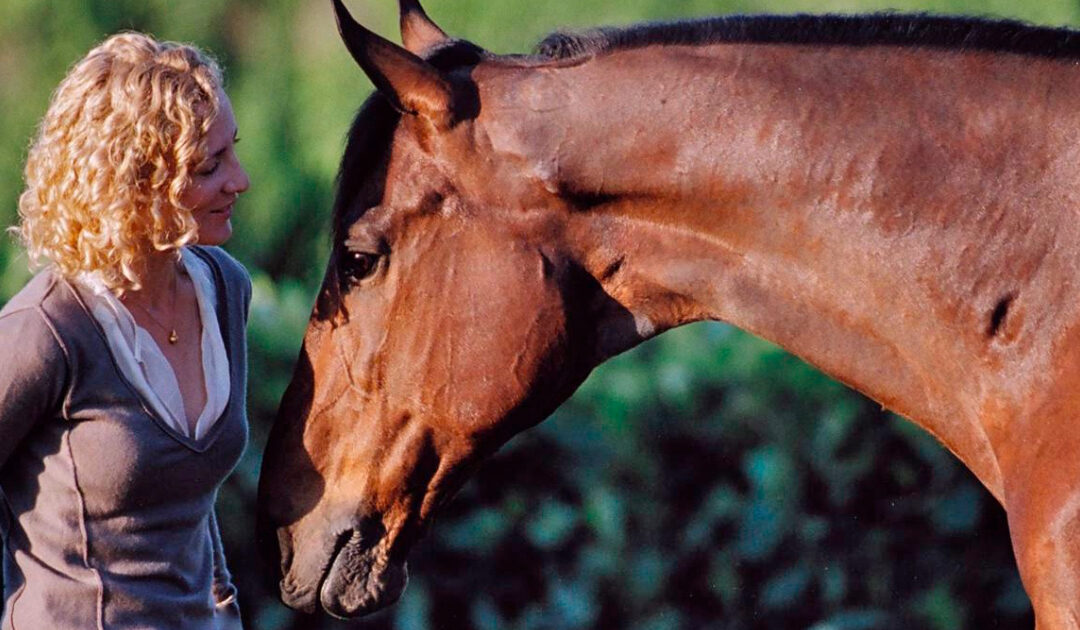

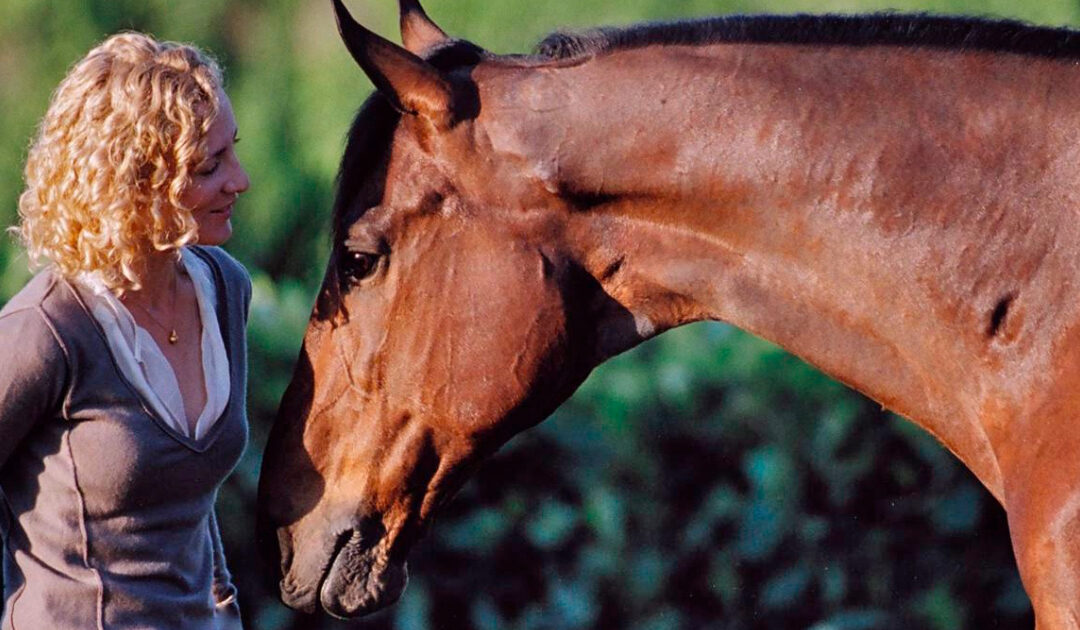

Feature photo by The Book, LLC, of Sarah and Hurricane in 2007. He was her Grand Prix jumping partner and soul-mate horse. He died in 2014.

Author bio:

Sarah Willeman Doran is a life coach, meditation teacher, and Natural Lifemanship practitioner. A former Grand Prix showjumping rider, she also breeds and develops young horses. She is the author of the blog Grappa Lane, about conscious living, horses, and psychology. She lives in Colorado.

by Laura McFarland | Dec 6, 2021 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship

By Laura McFarland

The following is an excerpt from the Natural Lifemanship Manual. Our manual is intended to serve as a resource to support students’ learning as they move through our Fundamentals and Intensive trainings. (The suggested citation is at the end of this article).

Connection is truly the way things are. Whether we are talking about the cosmos, biological systems, ecological systems, sociocultural systems, or family systems, we exist in a world of relationships. The health and vitality of each individual is inextricably tied to the health of his or her connections.

As humans and as mammals, we seek safety and comfort in connection with our families, our tribes and our herds. Connections are meant to be protective and nurturing forces in our lives, especially when we are young and dependent on others for our care. We are biologically primed to desire connection and when it is disrupted, to seek its repair.

Our personal and our collective well-being and healing rest on the powerful, transformative, life-giving experience of connection.

To practice Natural Lifemanship (NL) is to engage in a process that puts connection above all else. The process helps humans and equines overcome the internal resistance to connection that we’ve acquired as a result of the hurts, mis-attunements, and traumas we’ve experienced.

We become defended in relationships when we experience them as abusive, neglectful, or objectifying. To the extent that these defenses are fortified, we find it hard to experience the very thing that we need the most. To be open to connection, we need to feel safe – our nervous systems need to tell us we’re safe.

Being a safe connection for others requires presence, receptiveness, and authenticity. It requires our own regulation so that our nervous systems are sources of co-regulation to others. To practice Natural Lifemanship is to strive for this in all of our relationships, and most definitely in our relationships with our clients and our horses.

From the safety of our connection, our clients become free to explore a connection with their horse and the horse is free to explore the same with their client. As the client learns to become a safe and receptive partner for the horse, their own healing comes about. They experience the healing flow of connection, and importantly, they are able to offer and to experience safety and connection in their human relationships, as well.

In Natural Lifemanship’s process of Trauma Informed Equine Assisted Therapy and/or Learning, TI-EAT/L, (understand our terminology), what happens in sessions doesn’t just stay in sessions.

It transfers by design.

How this works and why it is important will become clear in the pages that follow, as you continue to move through training with us, and as you begin to explore and experience it in your actual relationships with humans and horses, both personally and professionally.

At the Natural Lifemanship Institute, our mission is to help people and animals form connected, trusting relationships to overcome toxic stress and trauma, and to work toward a world where connection and the value of healthy relationships is seen and felt in everything we do.

To begin a journey with us is to commit to the healing of self, your clients, your communities, and your horses – the ripple effect if staggering! We would be honored to embark on this journey with you.

Registration for the next Fundamentals of Natural Lifemanship training opens January 12th!

The picture at the top of this blog post was used courtesy of Lisa Kruse and her son LuCasey. Lisa Kruse is an NL Practitioner and LPC who practices in Dallas, Texas.

Copyright © by Natural Lifemanship, LLC. All rights reserved.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Jobe, T., Shultz-Jobe, B., McFarland, L. & Naylor, K. (2021). Natural Lifemanship’s Trauma Informed Equine Assisted Services. Liberty Hill: Natural Lifemanship.

by Bettina Shultz-Jobe, LPC, NBCC | Dec 6, 2021 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship

By Bettina Shultz-Jobe, Tim Jobe, Kate Naylor, and Laura McFarland

The following is an excerpt from the Natural Lifemanship Manual. Our manual is intended to serve as a resource to support students’ learning as they move through our Fundamentals and Intensive trainings. (The suggested citation is at the end of this article)

When people are uncertain about something in their lives, they seek guidance. Frequently, guidance comes in the form of instructions or advice – someone telling us what to do. But each of us is a unique individual, with subtle differences and nuanced needs, and so are the animals and clients with whom we work.

At The Natural Lifemanship Institute, we strive to recognize the individuality of each being and offer guidance on the subject of Equine Assisted Services with this in mind. This means, though, that prescriptive advice on “what to do” is extremely limiting – it does not allow for the individuality of you, the doer, and others, the recipients of your doing.

This is why NL is principle-based rather than technique focused – rather than offer you things to do, we aim to give you ideas from which to cultivate your own thinking, and for your clients to develop their own thinking.

Principles offer structure without dictating the details.

Our principles are our beliefs. They are what we see as truths in the world, for humans and non-humans alike based on decades of observation, experience, and research science. You and your clients will come to develop your own principles as well – this is an important part of the therapeutic process.

We teach from principles for several reasons,

1) Our principles let you know who we are (our values, ethics, motivations, and goals)

2) Teaching from principles allows you to understand the “why” of our and your choices, rather than only offering you the “what” – enabling you to use your full self, your creativity and unique gifts and skills, in response to the complete individuality of the “other” with whom you are engaged, and

3) Because principles transfer from horse to human to the world at large, and techniques don’t.

For example, imagine a client, facilitator, and equine professional riding in an arena for their session. As the three riders pick up a trot, the client begins to bounce in the saddle while the two members of the facilitation team do not. The client notices this in frustration, and wants help to ride the trot better.

A technique focus would motivate the team to coach the client to, for example, put his heels down, keep his hands still and soft, and sit deeper in the saddle. This advice might improve his riding, but what does it offer him outside of this moment? What does he take home to remember and use with his family, his peers, in his own body, and in his relationships with the world around him?

If we revisit this moment from a principle-based perspective, we look at the “why” underneath the behavior of the client bouncing in the saddle. Brain science and relational principles tell us that when stress increases, it is harder to control ourselves – we get discombobulated and disorganized.

So the issue is not hands or heels, it is stress and the body’s response to stress that are causing the hands and heels to be out of control. What the client needs then, is more development of regulation skills – skills for organizing himself in moments of stress.

The facilitators, coming from this wider perspective, can begin to help the client tune in to his body’s response to the stress of trotting so he can become more aware of what is happening internally. He is encouraged to notice his heart rate, his breathing, his muscle tension and practice ways to calm himself, release tension, breathe more deeply…all things the team supports him in developing.

THIS he can take into the rest of his life, as well as improve his riding.

The client now has practiced attuning and attending to his internal experience during stress – an important life skill. And, because the guiding principle is simply that stress causes disorganization (which feels like chaos) and healing requires organization (calm/regulation) – the therapy team has a wide variety of options on where exactly to go next with this particular client.

The goal is to get reorganized around stress – the paths are many, and are dictated by the therapy team’s scope of practice and unique skill set. A coach will approach this moment differently than a somatic therapist, who would approach things differently than an OT, who would approach things differently than a child psychologist with training in mindfulness – but each professional can be guided by this principle of disorganization and reorganization, of stress and calm.

Note that this is not the only principle at play in this example, but one of many…. another principle may be that regardless of the task, connection is the goal. Guiding the client to connect with himself, and connect more deeply with his horse, would be a practice that serves him both in and out of the saddle.

A principle based approach offers guidance AND allows for individuality and creativity–– an organic unfolding of the therapeutic process.

With this in mind, here is a list of principles we find to be true and that guide our work. Oftentimes, we think of these truths as Laws of the Universe: Rules I didn’t make, so I can’t change them.

This list is by no means exhaustive, and hopefully, allows space for compelling conversation as you continue your learning journey with us!

- A good principle is a good principle regardless of where it is applied

- The relationship is the vehicle for change

- Principles transfer, techniques do not

- If it’s not good for both, eventually it’s not good for either

- True healing cannot happen at the expense of another

- The way you do anything is the way you do everything

- Knowledge cannot be pushed into a brain, it must be pulled in

- Consent is a clear “yes” that is freely given; rather than simply the absence of a “no”

- All beings have the right to choice: choice to resist, ignore, or connect/cooperate with a request with freedom from fear of punishment

- Animal welfare issues are also clinical issues

- Regardless of the task or activity, a connected relationship is always the goal

- Relationships begin with requests

- There is no effective self-regulation without safe co-regulation first

- Pressure is a natural fact of life so how we apply it and respond to it is very important.

- In healthy relationships and secure attachment, the internal, felt sense of connection remains whether the relationship partner is physically present or not

- Connection with self is not necessary before we can connect with others, but it is necessary in order to request connection from others

- Control and connection cannot coexist – this is true as it relates to connection with self and others

- Objects can be metaphors, living beings cannot

- We can learn about healthy relationships through simpler interactions with horses

- Animals are sentient beings

- The relationship with the horse is a real relationship. Therefore, the horse is not a tool, a metaphor, an instrument, a mirror, or a deity.

- If we truly want to have healthy, connected relationships with our horses we must shift our focus from what is good for THE horse to what is good for THIS horse.

- Horses will respond now the way humans will. . . eventually.

- Having healthy boundaries is about focusing on what I want/need instead of focusing on what I don’t want/need. The need to “set” boundaries is a connection issue.

- Communication must be seen within its context – the individuals, environment, and moment in time

- Brain integration ⟺ Secure Attachment

- Regardless of what is going on around me, it is possible to manage what is happening inside of me

- If you cannot appropriately manage yourself, someone else will

- Safety comes from a connected relationship; connection cannot come from arbitrary safety rules

- Rupture and repair are inevitable and necessary when building connection and healthy relationships.

- Relationships don’t require nor can they tolerate perfection. In the face of perfection there is no room for grace or growth. Relationships need both.

- The horse doesn’t know who the “client” is which is why our own personal growth and awareness is so important

- Who we are in session is more important that what we do

- What you DO is technique, who you ARE is principle

Registration for the next Fundamentals of Natural Lifemanship training opens January 12th! We hope to see you there.

Copyright © by Natural Lifemanship, LLC. All rights reserved.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Jobe, T., Shultz-Jobe, B., McFarland, L. & Naylor, K. (2021). Natural Lifemanship’s Trauma Informed Equine Assisted Services. Liberty Hill: Natural Lifemanship.

by Kate Naylor | Jan 13, 2021 | Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Equine Assisted Trainings, The Latest in Equine Assisted Therapy and Learning

By Kate Naylor and Bettina Shultz-Jobe

Jumping into the field of Equine Assisted Therapy (EAT), Equine Assisted Psychotherapy (EAP), and/or Equine Assisted Learning (EAL) can be daunting – figuring out how to be properly trained and prepared can be even more so.

You can’t just google “get certified” and find a website that explains it all. It’s a bit of the wild west out here – so many teachers to choose from, so many approaches, and no central rules or regulation.

So what is an aspiring equine assisted practitioner to do?

The short answer is “do your research”…but, that’s not a very satisfying answer, is it?

So, we at The Natural Lifemanship Institute have put together a list of things we consider to be incredibly important to a thorough and quality certification in Equine Assisted Services (our inclusive term for EAT, EAP, and EAL) – and we’d like to share it with you!

Over the three decades that Natural Lifemanship founders Bettina and Tim Jobe have worked in the field of Equine Assisted Services (EAS), they have learned quite a bit about what is needed for effective, ethical practice.

It isn’t a simple process, nor should it be…because when you enter a field in which expertise is needed in both the human and equine realm, there is a lot to learn. Of course, we would love for you to train and get certified with us…but more than that, we want you to find exactly what you need to nurture your continued growth in this ever-growing field. Below are our Ten Things You Need to Know When Choosing an EAS Certification – we hope it is helpful!

1. Teacher Experience!

First and foremost, as you begin a certification, you want to know you are in capable hands. This is why understanding the qualifications of your teachers and trainers is so important.

Consider their experience!

How long have they been doing actual EAS work? In this newer field, many teachers may have great ideas but haven’t actually been offering EAS sessions for very long, or for very many total hours of practice. Consider some practitioners see 25 clients a week while others might only see one or two – weeks and months may not be the best measure of experience.

Time in the “pen”, so to speak, makes a world of difference when you are teaching both theory and skills. So as you do your research, ask yourself, how many hours of experience does this trainer have?

Malcolm Gladwell argues it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill…do your teachers come even close to that in either clinical experience, horse experience, or both?

2. Excellent Equine Experience!

Understanding the nuance of relating to equines and partnering with them in this work is a process that can only evolve with time, practice, and seasoned guidance.

Working with equines is just like any other relationship – intimacy, trust, and clear communication come with intentional effort over time. . .

There are no shortcuts to good horsemanship. Be careful of programs suggesting otherwise – there are no cheat sheets and quick fixes to understanding the complex and often understated ways equines communicate their needs.

Each one is an individual.

Not only is it important to learn about general equine behavior, learning, and communication, it is also important to learn about the specific equines with which you hope to work.

This takes time.

3. Clear ethics!

As you search for a program, consider the language that is used and the ethics that are both implied and explicitly stated.

The ethical motivations and underpinnings of any good certification program should be clear and readily available to you.

How does a program see the clients, the animals, and the therapy team? How does the program value experience, working within one’s skill set, perspective, theoretical underpinnings, acknowledgment of science/research, and a practitioner’s personal growth?

All of these are areas needing attention and guidance if one is to practice any helping profession ethically. It should also be evident that there are checks and balances in the approach itself, to safeguard against damaging bias and countertransference.

4. Personal Growth!

As NL says “the horse doesn’t know who the client is”…in our unique field we are relying on feedback and communication from our equine partners to help us move forward in our relationships with our clients.

Because we cannot ensure our equines only pay attention to client issues, our own patterns and internal experiences absolutely will and do influence our sessions.

Therefore, we cannot separate our own personal development from our professional development. A quality certification program will require you to consider your own internal experience as much as the client’s and horse’s in order for you to become a more conscious and effective practitioner.

Reflecting on your own relational history, your personal blind spots, triggers, motivations, and being in tune with your own body/mind/spirit should all be valued in your professional development.

5. Depth and breadth of learning!

What would you prefer if you were a client – a practitioner who had spent 5 days learning EAS, or a practitioner who had spent a year (or more) in coursework, practice, supervision, and consultation?

The requirements for certification in the EAS field are wide and varied – pay close attention to what it takes to become certified and consider the client perspective. What is best for our clients, who have little to no information about what it takes to say “certified in EAP, EAT, or EAL”?

Programs of excellence should offer theoretical and scientific underpinnings for their approach to both equines and humans – and should give you plenty of hours of not only learning but practice and reflection as well.

6. Practical Experience!

Practical experience is where the deeper learning happens…it is where theory is infused with reality, where cognitive information becomes embodied, where knowledge becomes wisdom, and where practitioners develop the “art” of their work.

Some programs do not require a practitioner to have ever worked with clients before becoming certified. Quality EAS isn’t just about what you know, it’s about what you do with what you know. Practical experience is necessary for quality work.

7. Trauma Informed Care!

The term “trauma informed care” has become a buzzword in recent years, but what does it really mean?

Trauma Informed Care means that practitioners operate from a foundation of knowledge based in brain science – it conveys an understanding of how life’s rhythms and relationships impact an adaptable brain and body from a macro level down to the smallest neurons.

This knowledge informs the way in which practitioners engage with clients AND their equines, both in and out of session.

Trauma Informed practitioners value relationship, rhythm, and science in their approach – it should be explicitly taught, as well as modeled in their everyday behavior.

Trauma Informed Care should create safety and flexibility in the certification learning environment as well as in client sessions.

8. A Blend of Science and Art!

Relationships are an art – an improvised dance informed by all that each individual carries within them as well as the energy between the two.

There is no doubt that intuition and experience are paramount to guiding clients through a healing process unique to their needs. However, there is so much that the relational neurosciences can offer us so that our work is better informed – making our art more effective.

It is common in our field to acknowledge the art of EAS, what is less common is the incorporation of the sciences that can inform and guide our individual approach.

The fields of interpersonal neurobiology, attachment, somatics, and more have transformed psychotherapy and our understanding of living beings, with so much to offer this work – it would be negligent to ignore them.

9. Individual Support!

No two journeys are the same.

A certification process needs to be flexible and helpful to your specific skills, goals, and dreams. Whether you are a seasoned clinician, an experienced horse professional, a student just starting out, or something in between or otherwise – you can reach your EAS goals.

Look for a certification process that not only considers your experience an asset but offers teachers who know your field of expertise.

EAS can be blended with a wide variety of therapeutic approaches – and the certification process should reflect that!

And finally, more than anything else…does a certification process offer you….

10. Relationship!

Rather than a nameless, faceless, and relation-less training process, how about one where you know your teachers, engage with them in a variety of ways on a variety of topics over time, and develop a supportive and engaging network of colleagues?

Relationships are the vehicle for change – whether in therapy, in learning something new, or out in day to day life.

Can you speak to someone when you need guidance? Do teachers care about your individual development? Is your time valued and respected? Relationships make all the difference.

So what kind of relationship do you want with your training and certifying organization?

Wondering how to get started with NL?

The Fundamentals of NL is the entry level training for all certification paths. The next cohort starts September 13th and registration is OPEN.

by Kate Naylor | Apr 6, 2020 | Applied Principles, Basics of Natural Lifemanship, Personal Growth

By Kate Naylor and Bettina Shultz-Jobe

In times of great grief, anxiety, stress, or fear why does it seem like words are unnecessary or even hurtful? We are verbal creatures, we have a great love for language. Just take a look at the astonishing collection of great written works we have accumulated – literature, poetry, lyrics, storytelling, and more. Words have given us new ideas, new frontiers, and abilities we never could have achieved before.

And yet, there are significant moments in our lives when words are insufficient, even counterproductive. Why is that?

Although we are a highly verbal species, we are not only a verbal species. We are an embodied species as well. We need so much more than words in order to truly feel seen by others, in order to truly be seen by our own selves. Our minds are an incredible gift, and yet they would be nothing without our bodies. Our minds know things, because of our bodies. The two together are what make us human.

So how do we care for our whole selves during this pandemic, a time of collective trauma?

As Larry McDaniel, an NL certification student and executive director and founder of Coyote Hill in Missouri, so beautifully states – words can only do so much, and then there is everything else.

Our brains and bodies begin forming in the womb, cells divide in an extraordinary choreographed dance that transforms these cells into a tiny body. This tiny body continues the dance of expansion and contraction – flexion and extension – reaching out and pulling in – in order to continue the development so needed for life outside the warm waters of their mother’s womb. What does this tiny body experience as it grows? The rhythmic whoosh of flowing blood and water, the bump bump bump of a heartbeat, the changes in gravity that come with the movement of the world around them as they are suspended in liquid. This is passive sensory input – sounds and sensations that a tiny body does not produce for themself, but receives freely. This is the foundation of brain and body development we all experience in some form – for some it is rhythmic, calm and nurturing, for others it is not, and still others it is something in between. But no matter what kind of womb experience, it is where we all begin.

Built upon this foundation are the movements this tiny body produces as they grow and stretch in the womb, and after in the world. These movements continue to develop the brain. Being held, pushing up, holding oneself, reaching out, grasping an object, and coming back to self again are all a part of our development – each one of us having individual experiences along the way. Built upon these movements are the relationships and meanings and memories that are created as this tiny body becomes a relational body as well. Who loves us? Who doesn’t? What does love and caring feel like? Is the world safe? We ask these questions and grow from the answers.

This development all begins in the womb, and continues after birth and on into a child’s life. This is how it is for all of us. Only lastly, do the words and thoughts come, when we are babies and young children, and on into adulthood.

The question of why words may not be sufficient during this time is important, and also clear once you understand where we come from. Words are insufficient because we are so much more than words. We are built, piece by piece, moment by moment, into the people we are today by our environment, our bodies, our relationships, our memories…as well as our thoughts and words.

So what can we do? As Larry says, we need music, and nature, and laughter and love – we need not just words but the other rhythms our whole selves are craving as well. In a more scientific sense, we need passive regulation from rhythm in our environment – music, nature (the sights, sounds, smells, and textures), sleep, food and drink, the warmth of other living beings, and a home environment that feels as predictable and soothing as possible (whether that be through routines, rituals, fabrics, light, sounds, smells, or all of the above). We need regulation for our sensory-motor (sensorimotor) circuits – we need to move in response to that passive sensory input we are receiving all the time. We need to sway to the wind in the trees. We need to dance to the songs that stir something within us. We need to cuddle into a soft blanket and withdraw from textures we dislike. We need to walk, run, and use our balance. Quite simply, our bodies need regular movement throughout the day to feel well – indoors or out, stimulating and soothing both. We need limbic stimulation and regulation through relationships and connection – with those in our home, with those we see through a video, with those we can hear on the phone. Being seen and heard, feeling loved and cared for, and doing the same for others…is necessary.

Words are beautiful and inspiring, AND we need so much more than words to feel human.

This is why Natural Lifemanship seeks to support YOU – our students, members, and anyone else who wants to join our amazing community – with rhythm and relationship during this time. It is our desire to support you in the most primitive of ways because our developmental foundations are all the same – our bodies, minds, and souls need rhythm, movement, and relationship to heal and grow.

Join us on FB live every Sunday at 5:30 p.m. CDT to build resilience as we connect across the globe through rhythm and movement.

Join us in small groups to build resilience through meditation.

Check out the most recent ways we are offering personal (and professional) support to YOU!

Sign up for our email list to receive weekly updates about available support during these difficult and uncertain times. NL is releasing new offerings each week! Feel free to tell us what you need – we are listening!

Recent Comments